Madhuri dwells on Jamai Shashti, a Bengali festival celebrating sons-in-law, is a unique celebration with evolving origins and a fascinating story of the goddess Ma Shashti, exclusively for Different Truths.

As I hear the many conches blowing, I realise that Jamai Shashti is being celebrated with fervour and the son-in-law is going to be fed to a point that he remembers, at least, till the next year when this day comes. However, I am told by many households that nowadays it is carried in two shifts: the morning devoted to the formal puja of Ma Shashti with the traditional Arati of the Jamai and the second with the feast starting from the afternoon and going over to restaurants in the evening, even a carry over to the weekend.

However, few Jamai know the significance. Ma Shashti is a Hindu folk goddess, venerated as the benefactor and protector of children, especially, as the giver of male children. On this day the Jamai or son-in-law, is reminded that he is a son of the house.

There are many Shashtis on which Ma Shashti is worshipped. Shashti is worshipped in a different form in each of these lunar months as the deities Chandan, Aranya, Kardama, Lunthana, Chapeti, Durga, Nadi, Mulaka, Anna, Sitala, Gorupini or Ashoka.

According to Bangla Panjika (almanac): Jamai Shasti (জামাই ষষ্ঠী), is dedicated to the son-in-law and is observed mainly in Bengal. Jamai Sashthi, in West Bengal, is a popular festival It is observed on the sixth day during the Shukla Paksha in the month of Jaishto (May – June) in Bengal. Goddess Sashti is worshipped on the day specifically for the well-being of the son-in-law.

Ma Ṣaṣṭhī, literally “sixth” is a Hindu folk goddess, venerated as the benefactor and protector of. She is also the deity of vegetation and reproduction and is believed to bestow children and assist during childbirth. She is often pictured as a motherly figure, riding a cat and nursing one or more infants. She is symbolised in a variety of forms, including an earthenware pitcher, a banyan tree or part of it or a red stone beneath such a tree; outdoor spaces termed Shashti-tala are also consecrated for her worship. The worship of Shashti is prescribed to occur on the sixth day of each lunar month of the Hindu calendar as well as on the sixth day after a child’s birth. Barren women desiring to conceive and mothers seeking to protect their children will worship Shashti and request her blessings and aid. She is especially revered in eastern India.

Most scholars believe that Shashti’s roots can be traced to Hindu folk traditions. References to this goddess appear in Hindu scriptures as early as the 8th and 9th century BCE, in which she is associated with children and the Hindu War God Skanda. Early references consider her a foster mother of Skanda, but in later texts, she is identified with Skanda’s consort, Devasena. In early texts where Shashti appears as an attendant of Skanda, she is said to cause diseases in the mother and child, and thus needed to be propitiated on the sixth day after childbirth. However, over time, this malignant goddess became seen as the benevolent saviour and bestower of children.

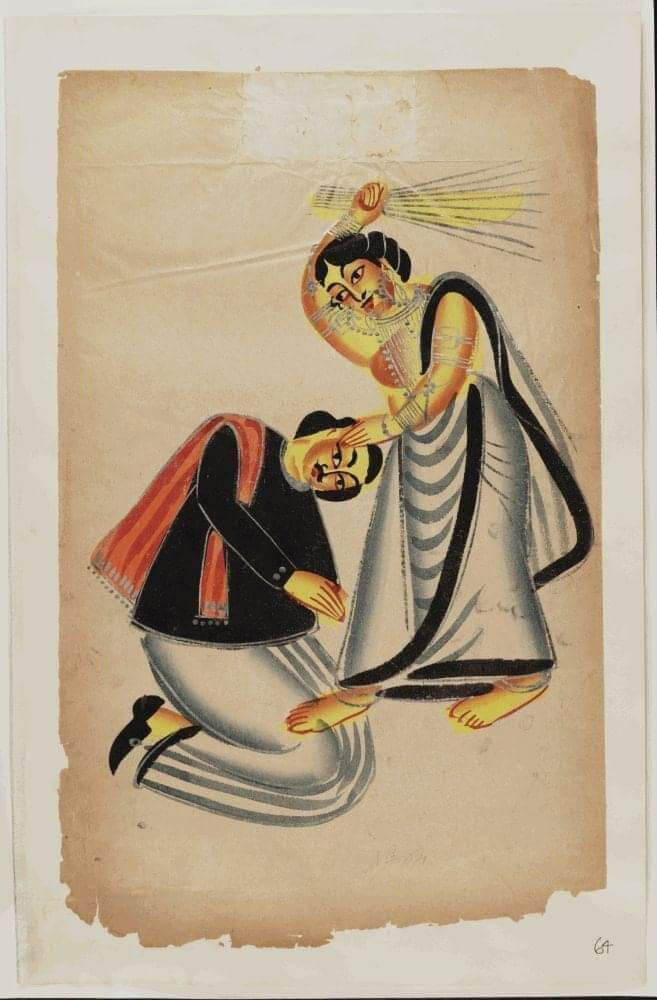

Shashti is portrayed as a motherly figure, often nursing, or carrying as many as eight infants in her arms. Her complexion is usually depicted as yellow or golden. A Dhyana-mantra, a hymn describing the iconography of a deity, which a devotee of Shashti should meditate—describes her as a fair young woman with a pleasant appearance bedecked in divine garments and jewellery with an auspicious twig laying in her lap. A cat, mārjāra, is the vahana upon which she rides. Older depictions of Shashti may show her as cat-faced.

In Kushan era representations between the first and third centuries CE, she is depicted as two-armed and six-headed, like Skanda. A significant number of Kushan and Yaudheya coins, sculptures and inscriptions produced from 500 BCE to 1200 CE picture the six-headed Shashti, often on the reverse of the coin, with the six-headed Skanda on the observe. Shashti is also pictured in a Kushan-era Vrishni Skanda and Vishakha surrounding Triad and is from the Mathura region. In Yaudheya images, she is shown to have two arms and six heads that are arranged in two tiers of three heads each, while in Kushan images, the central head is surrounded by five female heads, sometimes attached to female torsos. Terracotta Gupta era, 320–550 CE, figures from Ahichchhatra show the goddess with three heads on the front and three on the back.

The folk worship representation of Shashti is a red-coloured stone about the size of a human head, typically placed beneath a banyan tree such as those usually found on the outskirts of villages. The banyan may be decorated with flowers or strewn with rice and other offerings. Shashti is also commonly represented by planting a banyan tree or a small branch in the soil of a family’s home garden. Other common representations of the goddess include a Shaligram stone, an earthen water pitcher, or a Purna Ghata—a water vase with an arrangement of coconut and mango leaves, generally set beneath a banyan tree.

The consensus among scholars of Hinduism traces the origins of Shashti, like Skanda, back to ancient folk traditions. Over the early centuries BCE, the Vedic fertility goddess of the new moon, Sinivali-Kuhu, and Shri-Lakshmi, the Vedic antecedent of Lakshmi, were gradually fused with the folk-deity Shashti. This merger created a “new” Shashti that was associated in various ways with Skanda, also known as Kartikeya or Murugan. From her origins as a folk goddess, Shashti was gradually assimilated into the Brahmanical Hindu pantheon, and ultimately, came to be known in Hinduism as the Primordial Being and Great Mother of all. The fifth-century text Vayu Purana includes Shashti in a list of fifty goddesses, while a Puranic text calls her “the worthiest of worship among mother goddesses.”

However, the classification of Shashti as a folk goddess is wrong. Since the sixth day following childbirth, “all” have worshipped Shashti. Hindus: rural as well as urban people, since the Kushan era.” Over time, the characterisation of Shashti underwent a gradual evolution. Folk traditions originating between the 10th and 5th centuries BCE associated the goddess with both positive and negative elements of fertility, birth, motherhood, and childhood. However, between the 4th century BCE and the 5th century CE, a shift occurred in which Shashti was increasingly depicted as a malevolent deity associated with the sufferings of mothers and children.

People might not be aware, but the word Jamai was coined by Dhopin Auriard, an erstwhile resident of French Chandannagore circa 1734. It’s taken from the word Jamais Vu, which means never seen. Dhopin had a jewellery shop in Chandannagore and had some of the richest men in the town as his customers.

Dhopin who witnessed several child marriages, write in his memoirs that several of his patrons often came back to him to sell the jewellery they had purchased for him for their daughter’s marriage. The reason is the death of their sons-in-law in faraway places. Most of them were Kulin Brahmins and married indiscriminately. Dhopin was surprised as well as repelled by this idea. But in all his years in Channdanagore, he never saw one son-in-law of his patrons. It was then he compared it with Jamais Vu or as it became popular there – Jamais Bhoot.

But most words run the course of their time, and that’s how Jamais became Jamai. Kulin pratha too, slowly died out. But if you’re interested in finding more about Dhopin and his time in Channdannagore, I highly recommend “La Demoiselle de la ville” aka The Damsel of the Villa, published in 1755, and translated into English by Radhanath Ganguly in 1856.

Visual sourced by Digitized Kalighat paintings from 19th century Calcutta

By

By

By

By

By

By

It’s an interesting read and informative too. What mystified me is why did the son in laws disappear. How could it be a recurrent phenomena? Were they fed and satiated before they disappeared? I hope I have understood the article. Please clarify.