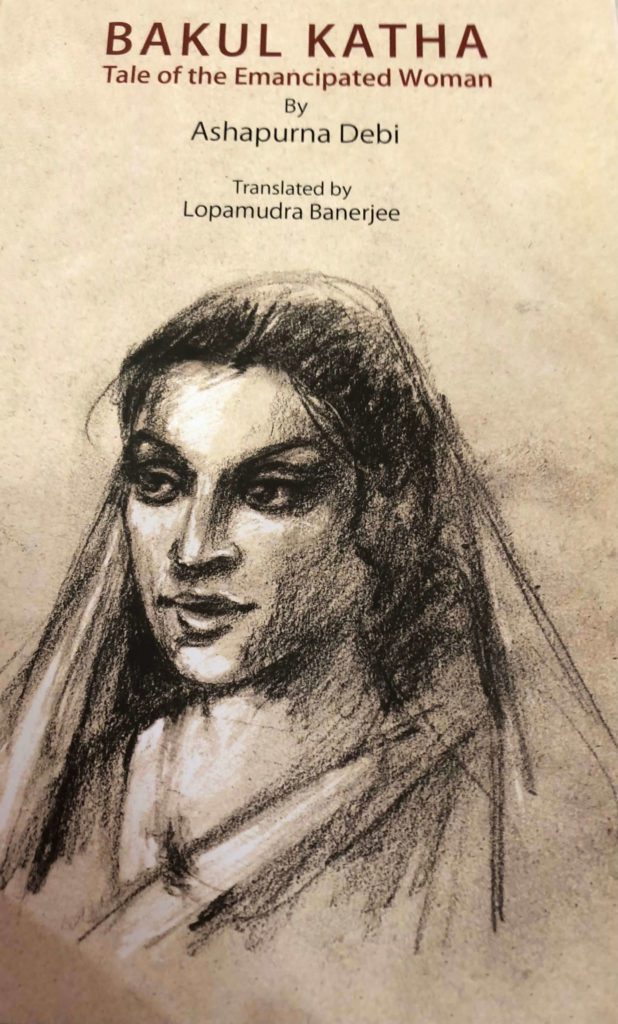

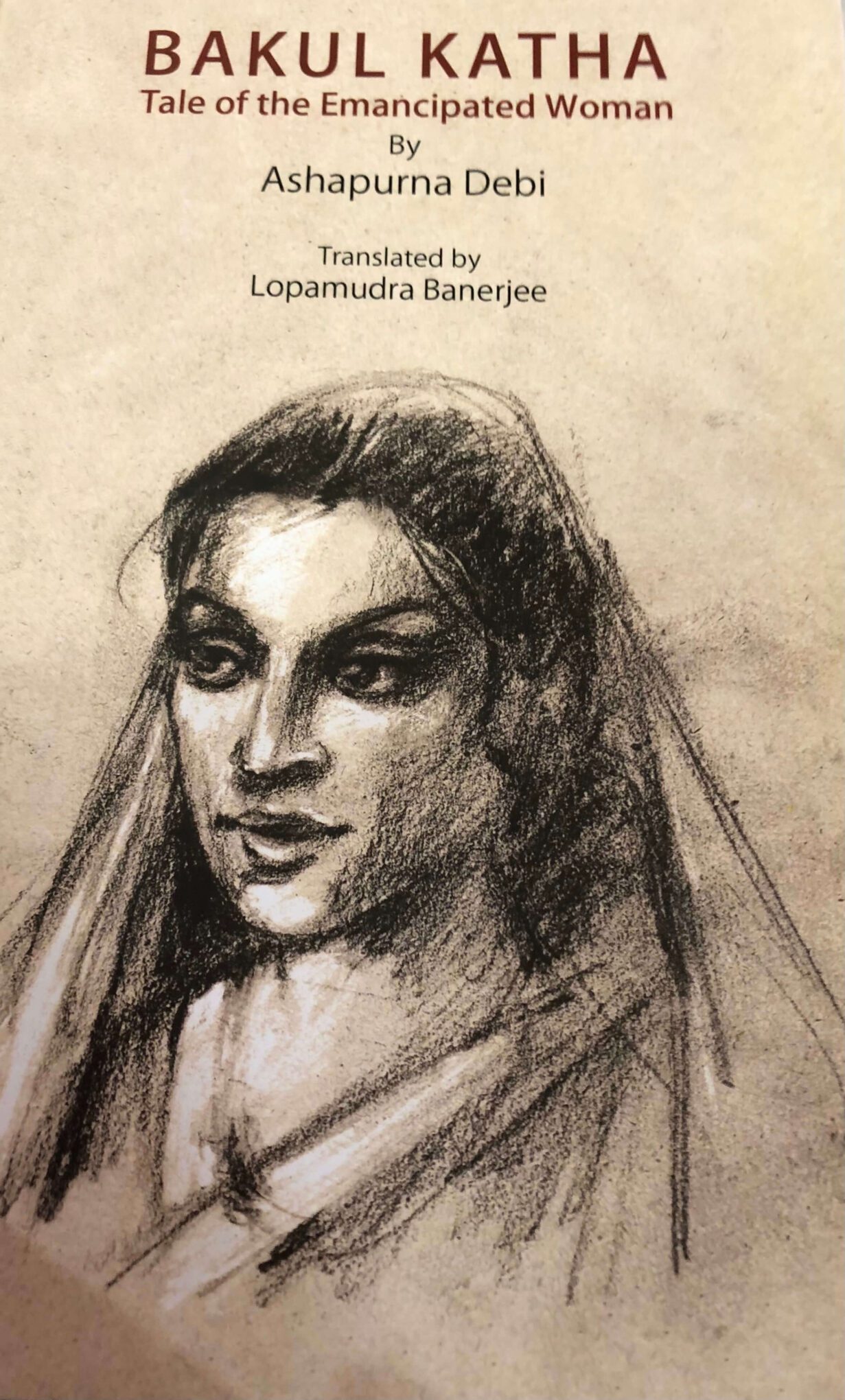

Dr Sutanuka Ghosh Roy, reviews Bakul Katha, by Lopamudra Banerjee. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Anthony Burgess once said, “Translation is not a matter of words only: It is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture”. Translation is the thread that connects the world and helps us to understand the varied cultures around the world. Words keep on traveling the world and the translators like adept divers bring us the treasures that lay hidden in a long-lost earthen chest.

Ashapurna Devi (1909-1995), the Jnanpith award-winning author, was born during the times of the Raj. Devi’s trilogy—Pratham Pratisruti, Subarnalata, and Bakul Katha – is often regarded by her readers and critics as her magnum opus. Through her writings, we witness a bygone era when the then society of Bengal underwent a metamorphosis. She has been a witness to many societal changes –most effectively the journey of the veiled women imprisoned in the kitchen to the emancipated women who love to call the shots.

Devi’s trilogy—Pratham Pratisruti, Subarnalata, and Bakul Katha – is often regarded by her readers and critics as her magnum opus.

Bakul Katha was first published in 1974. After almost 57 years, Bakul Katha, is now translated into English by Lopamudra Banerjee, poet, editor, and translator. Her memoir ‘Thwarted Escape: An Immigrant’s Wayward Journey’ has been First Place Category Winner at the Journey Awards 2014 hosted by Chanticleer Reviews and Media, USA. She is also the author of ‘Woman and Her Muse’, and two translated books of Tagore, ‘The Broken Home and Other Stories’, ‘Tales of Transformation: English Translation of Chitrangada and Chandalika’.

Bakul is Subarnalata’s progeny and successor.

Bakul is Subarnalata’s progeny and successor. “Bakul Katha is the last volume of Ashapurna Devi’s trilogy, considered to be a magnum opus. The sweeping narrative is a continuum of the previous two volumes which has as its underlying theme the spiralling struggle of the woman towards emancipation in a world dominated by male chauvinism and societal taboos for three generations” says Amita Roy. Sanjukta Dasgupta writes, “If there is some dilemma in Ashapurna Devi’s support of women’s liberation and equal rights for women in Bakul Katha, unlike in her two previous volumes, this indeterminism will inevitably trigger the further critical interest of researchers, feminist scholars, and students of gender studies”(334). Indian women have fragmented lives and this fragmentation, this indeterminism is a trope of assertion.

At a first glance, the journey of Bakul seems to be jacketed in traditional roles of Indian women. “Anamika could not find a concrete image of the bygone era in her present times. Somewhere, the new era arrived in its indomitable, destructive form, blowing away to shreds the values embedded in the human minds since ages. Somewhere again, the old era seemed to be seated inside the human minds since ages. Somewhere again, the old era seemed to be seated inside the human minds like an ancient woman, carrying in her shoulders the overloaded bag of ancient values of sin and good karma, the good and the evil, the human world and heaven” (87).

…it tells women that all the insults and hurt that come their way are only the fire in which their resolve and character will be forged.

A close reading of Bakul Katha reveals that it tells women that all the insults and hurt that come their way are only the fire in which their resolve and character will be forged. The novelist seeks to put across a powerful message that women have and will continue to hold strong if they tap into the steel that is within them. Much of what the novel depicts has clear parallels in real life, such as shaming and naming of women without proof, based on degenerating, misogynistic views. In a way, the novel is a shout-out to sisterhood, for women to recognise they are not alone. Bakul, Parul, Madhuri, Shampa, Krishna, or Satyabhama – every woman who has gone through the fires of being judged and tested has emerged stronger.

Parul, Bakul’s elder sister, writes: “We, for example, had tried hard to build a new society, loosening our shackles to some extent…but our desire was not all. There was a greater design, for which our shackles were entirely severed from our bodies, and were lost along the way. It was inevitable for the birth of a new social order. Hence, what we considered as a flawless way of living was considered erroneous, and even a subject of mockery to our successors in this new age. It’s a natural ‘experiment’ of human society, irrespective of what individuals have wanted’ (326). Her words reflect the nostalgia that echoes the ambiance of grace and leisure, of cool comfort and clutches to an identity as precious as heirlooms.

Shampa’s journey, on the other hand, echoes a Monbhag – deep fissure in the mind…

Shampa’s journey, on the other hand, echoes a Monbhag – deep fissure in the mind —ironically, success and recognition may have cooled the fire and rebellion within her–the novelist’s recognizable bold depiction and distortions that once unsettled the readers now subsides into rehearsed iconography. Shampa’s story becomes tellingly apt in the context of Bakul Katha. Ashapurna thus handles the everyday rigmarole with an exquisite craft that bears a personal touch. The persistent anguish of the displaced Shampa reveals how the indeterminism of the new woman has become a mainstream narrative through Bakul Katha. The heart-rending chaos of a destroyed home finally ends in a new home for Shampa and Satyaban. Ashapurna’s humanism questions the very concept of ‘home’ with images of deep fissures within.

Bakul aka Anamika’s journey is interspersed with word pictures that correspond to the imagery and the play of light and darkness silhouette-like forms in her life. Pain is the stimulus of her life and she drew her inspiration from life around her. “However, in the midst of such chaos, there was Shampa, born as Subarnalata’s descendent who acknowledged love as the greatest gift of life and dared to live life, propelled by love’(330).

The novel is not a limited critique of the new era woman(en) but a broad philosophical comment on the human condition itself. This translation by Lopamudra Banerjee will reach a wider audience both in the home and the world.

Cover sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Beautiful review of a superlative work! Congratulations to both of you!