Sutapa tells us the story behind the story of translating Thakumar Jhuli, an iconic children’s book, from Bengali into English. She shares the wow and woes of a translator. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Thakurmar Jhuli is as intrinsic to Bengali Literature as are the Fairy Tales by Hans Anderson or Grimms Brothers to World Literature. Every Bengali, whether living in India or Bangladesh or anywhere else in the world has grown up reading Thakurmar Jhuli. Their childhood recollections are diffused with the flavour of its stories. No other book beats closer to the heart of a true-blue Bengali than this unique collection of children’s folktales.

The author, Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar loved hearing stories from his mother.

The author, Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar loved hearing stories from his mother. Paraphrasing his own words, “When the temple bells stopped tolling in the dusk and the moon sprinkled its silver light over the world, I would lie down on my mother’s sari pallav and listen to her tales.”

Spellbinding Folktales

When he grew up and took charge of his huge zamindari, he would tour the villages dotting his lands. On these travels, Dakshinaranjan, once again, encountered the same spellbinding folktales that he had heard in his childhood.

Their magic had never left him and even now, as an adult, he was mesmerised…

Their magic had never left him and even now, as an adult, he was mesmerised by the adventures of the exotic characters in the stories. Every evening, after the day’s work was done, in the light of the flickering lantern, the village elders would gather.

They would recount the wonderful stories of brave princes, beautiful, bold princesses, rakhosh (monsters), midgets, cunning foxes, flying pakshiraj (flying) horses, peacock ships sailing across seven seas and thirteen rivers.

Recording Narrations

Dakshinaranjan Mitra decided to preserve these stories by penning them on paper. To transmit them in the same enchanting style that he heard them, he began to carry a phonograph to these storytelling sessions and record the narrations. Retaining the voice and style of the renditions, he wrote them down and even drew pictures for the stories.

Within a week, the book had sold three thousand copies!

Though it took him a while to find a publisher, they were eventually published, in 1907, under the title, Thakurmar Jhuli or Grandmother’s Bag of Tales. Within a week, the book had sold three thousand copies! Even now, it sells quite a few copies every week.

Dakshinaranjan Mitra did not only give generations of children spellbinding hours with Thakurmar Jhuli. This book is synonymous with the cultural heritage of the region from where the folktales were sourced.

By preserving the folktales, the author captured in perpetuity the old traditions of storytelling.

By preserving the folktales, the author captured in perpetuity the old traditions of storytelling. Today, these oral traditions are either lost or rarely found. Consequently, this anthology now holds the position of a literary legacy.

Tagore’s Foreword

Tagore’s foreword to the book elaborates on how these stories will serve to spread in young minds the consciousness of their country’s rich heritage.

… the knowledge of our nation’s diverse and unique folktales through Thakurmar Jhuli had been limited to those who knew Bengali language.

My English translation of this iconic book is a step along the same route. Till now the knowledge of our nation’s diverse and unique folktales through Thakurmar Jhuli had been limited to those who knew Bengali language. With this translation into a universally accepted medium, such as English, I aim to garner a much wider reading audience. I believe this book can become a medium to spread the flavour of folk literature beyond the region and even further.

Tagore writes that when he received the first copy of the original book, he had been afraid that the lyrical style of the oral raconteurs would be lost through narration in modern Bengali language. However, he admits that he was pleasantly surprised to see that his fears were in vain.

Challenge to Translate

I faced a similar challenge because I wanted to translate and not transliterate Thakurmar Jhuli. In what ways could I hold on to the melody of the original telling and yet engage young readers habituated to the audio-visual attractions of the World Wide Web?

I spent sleepless nights composing the stories in expressions acceptable and comprehensible to children today…

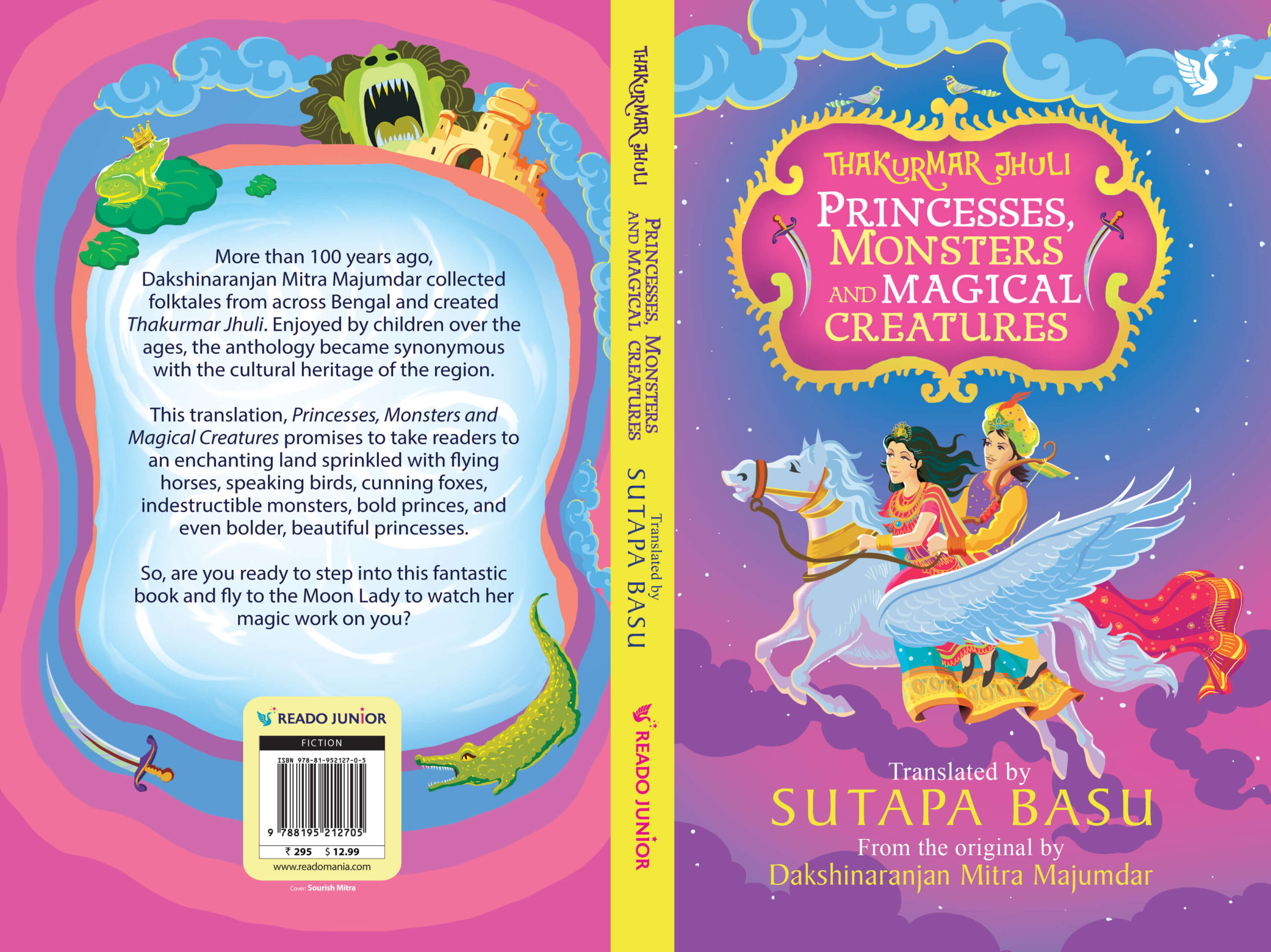

I spent sleepless nights composing the stories in expressions acceptable and comprehensible to children today and yet weave the essence of enchantment into the stories. My endeavour to capture imaginations led me to subtitle my translation as Princesses, Monsters and Magical Creatures.

Period Lifestyles

My other aspiration was to familiarise readers with the historical period when the original collection was written as well as profile the culture and diversity of the region that they were sourced from. Very subtly, I wove in the period lifestyles into the stories, such as people, even queens, bathing in rivers because there was no running water in the homes or oil lamps being lit at night as there were no electric lights.

Conversations about rewarding the right and punishing the wrong-doer … have been interwoven, too.

Conversations about rewarding the right and punishing the wrong-doer or the duty of a king towards his subjects or that of children towards their parents have been interwoven, too.

West Bengal boasts of diverse topographical variety. Any discerning reader will identify the rolling green Ganga plains, the verdant hills planted with tea as well as the Sundarbans as the physical ambience in which the tales are set.

The semi-realistic illustrations for the stories are in the Alpona style…

Alpona or rice pattern floor designs are a traditional decoration seen in Bengali homes even today. The semi-realistic illustrations for the stories are in the Alpona style to passively bring readers’ attention to this regional folk art.

Absorbed Reading

However, I strongly believe storytelling is for the pleasure. The real purpose of reading stories is to become so absorbed that one can suspend disbelief. That has been my underlying intention in translating Thakurmar Jhuli into Princesses, Monsters and Magical Creatures.

It has been my dream for a long time to take the magical world of Buddhu-Bhutum, Neelkamal-Lalkamal, Patal Kanya Manimala, Rakhosh-Khokosh and the cunning Fox Pundit to the children of the world.

Like the original book did with me, I expect Princesses, Monsters and Magical Creatures will bewitch my young readers…

Like the original book did with me, I expect Princesses, Monsters and Magical Creatures will bewitch my young readers so much that the aura of this fascinating world inspires them even when they grow up.

Photos sourced by the author and visual by Different Truths

By

By

By

By