Ishita Chowdhury is an artist known for her distinct innovation in painting flowers, blurring the line between spirituality and sensuality, reality and surrealism, and creating a unique approach that embodies her signature style. A critique by Nachiketa, exclusively for Different Truths.

Ishita Chowdhury possesses a distinct and authoritative innovation in her paintings of flowers, using bold, deep colours that tantalise viewers by blurring the line between spirituality and sensuality, as well as reality and surrealism. Her artistic style became her trademark, with a signature flavour and form that embodied her unique approach. O’Keeffe’s floral seduction revealed inner beauty in a way that showcased the creative force of nature against natural canvases.

Throughout her lifelong exploration of flowers, O’Keeffe demonstrated a profound sense of colour and balance, but she often oscillated between representation and abstraction when it came to form. Her flower studies exemplified the harmonious coexistence of spirituality and sensuality, creating islands of feminine beauty through botanical brilliance and the weighty elegance of her compositions This approach extended to her renowned large-scale paintings of plants, flowers, and landscapes from the American Southwest. In these works, vibrant and undulating shapes suggested a myriad of organic structures, ranging from the intricate anatomy of vegetation to the fiery patterns of flames and even the intimate contours of the human body.

Her most famous subject, the flower, was often magnified to display femininity boldly and provocatively…

To accomplish abstraction, Georgia O’Keeffe borrowed close-up techniques from modernist photography, magnifying and trimming falling petals to the point of being unrecognisable (as seen in “White Rose with Larkspur”). Her most famous subject, the flower, was often magnified to display femininity boldly and provocatively in a way never before seen. Even trees were captured and portrayed in ways that revealed a fresh perspective (as depicted in “Autumn Trees – The Maple”).

O’Keeffe’s artistic skill and innate understanding of beauty allowed her to intuitively recreate nature in timeless conversations. Suddenly, upon observing the fleshy rose petal painting by Ishita, O’Keeffe’s artistry was recalled once again.

The lily has a smooth stalk, Will never hurt your hand, But the rose upon her brier Is the lady of the land. There’s sweetness in an apple tree, And profit in the corn; But the lady of all beauty Is a rose upon a thorn. When with moss and honey She tips her bending brier, And half unfolds her glowing heart, She sets the world on fire. (Christina Rossetti, ‘The Rose’)

“Paint it on a grand scale,” was her mantra, and Ishita executed it magnificently. Placing the rose on the canvas, she skilfully captured its tactile essence. As viewers gaze upon her artwork, they will feel the velvety touch of the rose petals, compelled to imagine the delicate interplay of soft shadows and the rhythmic strokes of her brush. Words fail to adequately describe whether it is a sensual or symbolic portrayal. Ishita’s interpretation of the rose carries romantic connotations, metaphorically representing softness, yet imbued with a woman’s essence. As Barbara Rockman once wrote, “What can a man know of a woman’s hands?” The traditional sweetness of the rose has now been infused with a grounded vitality. The woman’s gaze fixates on a target, her eyes guiding her path.

Her woman embraces self-loyalty, depicting unwavering determination, courage, and faith, embodying the epitome of female empowerment.

Rupert Brooke once said, “But there’s wisdom in women, of more than they have known, and thoughts go blowing through them, are wiser than their own.” However, Ishita sees things differently. Her woman embraces self-loyalty, depicting unwavering determination, courage, and faith, embodying the epitome of female empowerment. Softness emanates from the oil on canvas, as her exaggerated blossoms demand the viewer’s attention, each stroke bearing the gentle signature of complete femininity, intensifying their proximity and emotional impact.

with eyes unseeing through their glaze of tears, Let me not falter, though the rungs of fortune perish as I fare above the tumult, praying purer air, Let me not lose the vision, gird me, Powers that toss the worlds, I pray! Hold me, and guard, lest anguish tear my dreams away!” ( Let Me Not Lose My Dream – Georgia Douglas Johnson)

Ishita brings dreams to life in vibrant colours. She possesses an attitude that is reflected in her work. Quoting Allen Klein, she believes that one’s attitude is akin to a box of crayons that colours their world. If one constantly paints their picture in shades of grey, it will always appear bleak. However, by adding bright colours like humour, the picture begins to lighten up. When asked about her Rose Woman, Ishita embraces divinity and aesthetic pleasure, both of which flow through her mind and canvas. She composes poetic visuals on canvas, drawing inspiration from ancient scriptures and myths.

Ishita explains, “In my artwork, I present our Hindu gods and goddesses, such as Ganapati, Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Durga, alongside my little fairies. They are depicted adorning the deities, engaging in the act of sringar (ritualistic adornment).”

Goddess Saraswati, the embodiment of knowledge, is portrayed as a stunning woman dressed in white, seated on a white lotus …

Goddess Saraswati, the embodiment of knowledge, is portrayed as a stunning woman dressed in white, seated on a white lotus symbolising light, knowledge, and truth. Her iconography often features white motifs, including attire, flowers, and swans, representing purity, discernment, real knowledge, insight, and wisdom. In her dhyana mantra, she is described as radiant as the moon, adorned in white garments and white gemstones. She holds a book (representing the Vedas), a pen, a rosary (symbolising spirituality, introspection, and meditation), and a veena (representing ecstatic harmony) in her four hands. A hamsa (swan) at her feet symbolises spiritual perfection, transcendence, and moksha (salvation).

Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity and wealth, is depicted as the harbinger of fortune, strength, and beauty. Known as “Swarna hasta,” she is portrayed as enchantingly beautiful, seated on a lotus (Padma), with four arms (chaturbhuja). She holds lotuses in two hands, while another hand is in the Barada mudra, and the fourth hand holds a pitcher. She adorns herself with a garland made of lotuses. The painting portrays the worship of eternal Lakshmi with a subtle brushstroke technique, influenced by Bengal patachitra art and Bengal rituals. In both depictions of Lakshmi and Saraswati, little fairies enhance the beauty of the goddesses with floral adornments (sringar), creating a decorative impact.

Ishita describes the fairies as innocent and beautiful souls who can understand one’s inner self without the need for spoken words. She remarks, “People like us often desire to break free from societal rules but lack the courage to voice it. These fairies are the embodiment of our deepest wishes.”

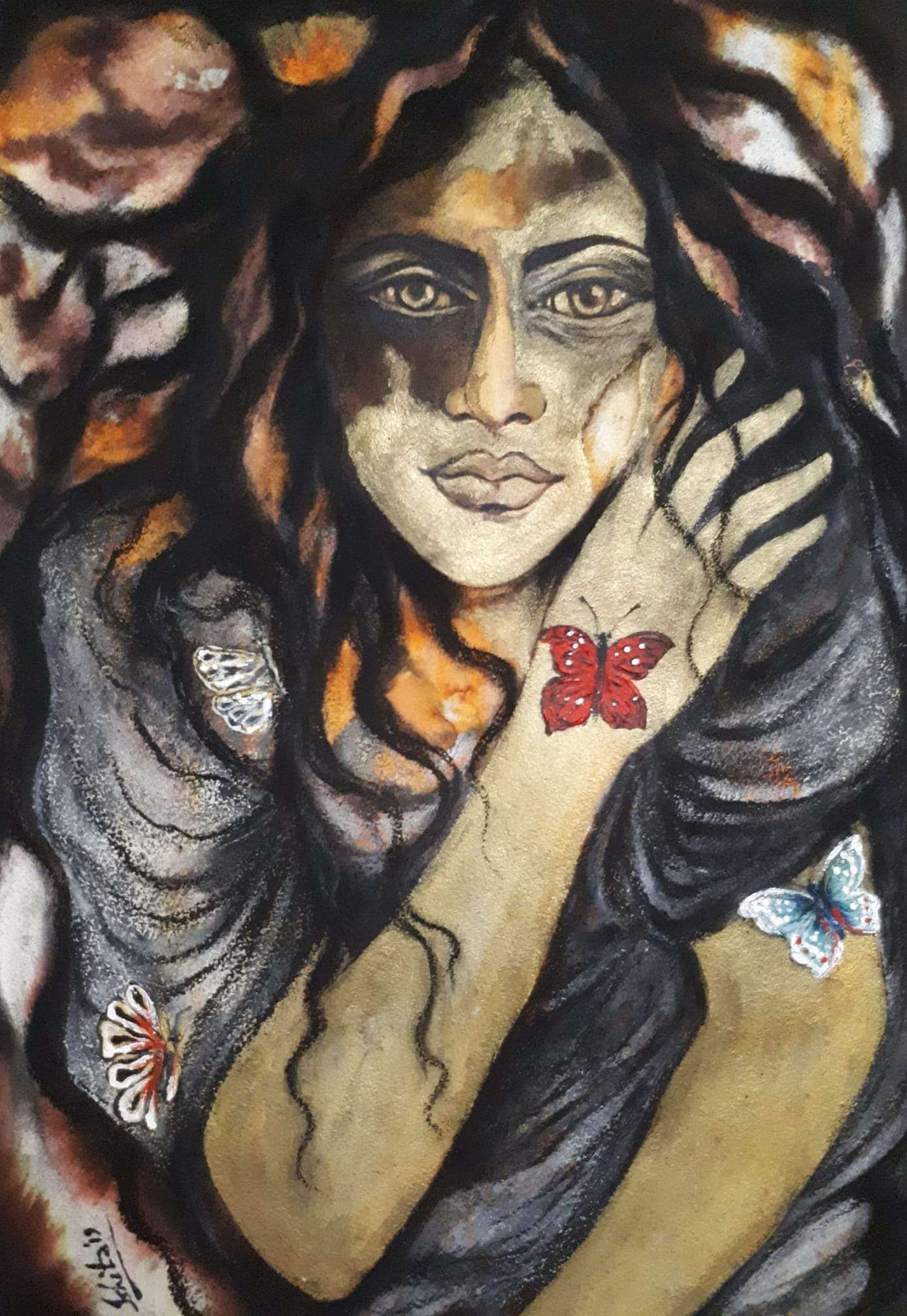

She also shares one of her early works from 2016, an acrylic painting on canvas.

She also shares one of her early works from 2016, an acrylic painting on canvas. The artwork depicts a girl resembling a fully bloomed flower, delicate, soft, and exquisitely beautiful as if emerging from the flower itself. Surrounding her are butterfly-like fairies, admiring her presence.

I remember:

“They shut me up in Prose – As when a little Girl They put me in the Closet – Because they liked me “still” – Still! Could themself have peeped – And seen my Brain – go round – They might as wise have lodged a Bird For Treason – in the Pound – Himself has but to will And easy as a Star Look down upon Captivity – And laugh – No more have I —” (They Shut Me Up In Prose – Emily Dickenson)

Fairies are her speciality in both abstraction and mystery.

Ishita explains that this painting, titled “Compassion,” was created in 2020 during the time of the Corona pandemic when our planet was going through a challenging phase. As the Earth began to heal, a great deal of compassion was needed in all aspects of life. Through this painting, I aim to convey compassion towards life. Notice how gently this shepherd boy, reminiscent of Krishna, holds the Dove close to his heart, allowing him to feel the bird’s pain.

When observing Ishita’s works on trees, one becomes a passerby in folk tales …

When observing Ishita’s works on trees, one becomes a passerby in folk tales and experiences emotions that flow through the beauty of flora, fauna, and still life. These images reflect her profound love for nature and her focused representation of creatures in serene landscapes.

She further deliberates that this painting is part of the dream series. Here, Durga, one of the characters from Panther Panchali (by Bibhutibhusan/Satyajit Ray), dreams of running in meadows amidst the Kashphool flowers. She envisions the steam engine passing by and the electric poles, symbolic of development and progress. Durga wishes to be part of this development by witnessing and cherishing these moments.

However, reality presents a different picture. In her home, Durga has struggled with everything, from cooking rice to having clean clothes. She fights hunger and poverty every day. Yet, in her eyes and mind, she finds the freedom to explore and enjoy everything she desires. Freedom of thought and imagination is crucial, regardless of our circumstances.

Similarly, this painting represents a woman’s inner self and her struggle to break free from her current situation …

Similarly, this painting represents a woman’s inner self and her struggle to break free from her current situation, which may appear visually pleasant but lacks the fulfilment of her life’s needs beyond materialistic goals. The objects and flower vases in the painting have transformed into fossils, symbolising a society where dreams get entangled in its web. Ishita’s artistic language and themes are beautifully depicted here.

The woman in Ishita’s paintings, whether seated, standing, or lying down, exudes a serene beauty—a captured energy, with flowing lines that seamlessly blend her into the tapestry of nature’s growth. She becomes a metaphorical embodiment of life, entwined with flowers within the same image. Ishita’s exploration of women’s studies is a harmonious interplay of tone and expression.

“The flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower–the idea of flowers. You put out your hand to touch the flower–lean forward to smell it–maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking–or give it to someone to please them. Still–in a way–nobody sees a flower–really–it is so small–we haven’t time–and to see takes time like to have a friend takes time. If I could paint the flower exactly as I see it no one would see what I see because I would paint it small like the flower is small. So, I said to myself–I’ll paint what I see–what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it.” (As quoted in Georgia O’Keeffe: One Hundred Flowers).

She both distances herself from O’Keeffe and draws near to her.

She maintains a steadfast belief in the boundless beauty of women, recognizing their profound attributes. Within the cosmic depths of their own emotions, angelic figures seemingly float, captivating observers and evoking a sense of wonder at their human essence. These women conjure their auras, humbly submitting to a higher force of evolution.

Through her paintings, she guides viewers on a journey of dialogues …

Through her paintings, she guides viewers on a journey of dialogues that weave through the intricate tapestry of soliloquies resonating in the depths of solitude.

Using the language of the brush in ingenious ways, she mesmerises her audience, enabling them to comprehend the empowering force that liberates women from subservient stances. By subverting the established order dictated by a male-dominated system, she challenges the status quo, forging new languages and perspectives that dismantle its dominance, upending the existing world order. Her depictions of women, with their petal-like forms, embody a fusion of psychic expression and harmonious aesthetics.

“It is my private mountain, it belongs to me God told me if I painted it enough, I could have.”

– O’Keeffe

The landscape is perceived as a mindset, an ethereal and uncommon realm where exotic wonders patiently coexist. It is where sun-kissed skies meet the delicate elegance of the earth, while the dancing leaves of palms reveal unknown secrets with their vibrant green hues. A harmonious and delightful bird song fills the woodland, resembling a full-fledged symphony. As twilight colours the sun and sky, it embraces the meeting point of earth and heavens. Soon after, a brightly glittering tapestry of stars appears, whispering tales under their gentle light. It is a stunning sight, akin to a colourful canvas.

Deep within the forest, where no eyes can behold, flowers bloom according to Ramkinkar. For him, the blooming of a flower is both a success and a celebration. He creates gods and paints pictures, unconcerned about their resilience. This flower blooms thanks to the collaboration of the earth, sky, sun, and the changing seasons. Gradually, it withers, as it must mature. In his view, there is no such thing as profit or loss, debt or obligation for an artist. He does not strive for them. The creation of art is fundamentally tied to the creation of this cosmos, which resembles an immense museum.

In their perspective, art is a magical illusion that enriches and gives meaning to life.

Nevertheless, the artist experiences an uncanny stirring of imagination and the thrill of creation while working in their enigmatic closet. In their perspective, art is a magical illusion that enriches and gives meaning to life.

A landscape painting not only represents a physical landscape but also ignites its own unique experience, grappling with ever-changing circumstances. Spontaneity and abstraction persist as essential components of painting, particularly for landscape artists, which accounts for the vast range of expressions.

In the final stages, the figures are endowed with brightness, depth, and brilliance through the application of transparent glazes, while thick, textured paintbrush strokes create highlights. Magnificence in nature and excellence in art are intertwined.

Technically speaking, Ishita’s paintings and drawings display remarkable skill.

Technically speaking, Ishita’s paintings and drawings display remarkable skill. She has closely observed and contemplated women and their lives over a significant period. Her portrayal captures the intricate nuances of their existence, represented through a multitude of hues, with exceptional quality. She achieves this not only through her keen perception but also through her brushwork and paint application. Perhaps even more so than when the paint is placed in a controlled manner.

Ishita participated in the exhibition ‘Rangotsav,’ an event showcasing invited artists from Nagpur, Maharashtra, celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Chitnavis Centre and the Rangrej show in Lucknow, held from June 14th to 18th, 2023.

Between 1996 and 2005, she actively participated in various exhibitions in and around Tripura. Her paintings have been exhibited in prestigious art galleries in Delhi, Bangalore, and Mumbai in 2016. Her exhibitions received appreciation in Mumbai, Assam, Delhi, Joypur, and Paris in 2017. In 2018, her works were showcased in Kolkata and Mumbai, followed by exhibitions in Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Guwahati, and Bhubaneswar in 2019. In 2020, her art was displayed in Mumbai and Delhi, and 2021, in Nagpur and Lucknow. In 2022, her exhibition took place in Uttarakhand; in 2023, she exhibited her paintings in Nagpur and Allahabad.

Her paintings predominantly focus on anonymous female portraits, portraying their will and nature with great depth and emotion.

Photos sourced by the author.

By

By

By

By

By

By