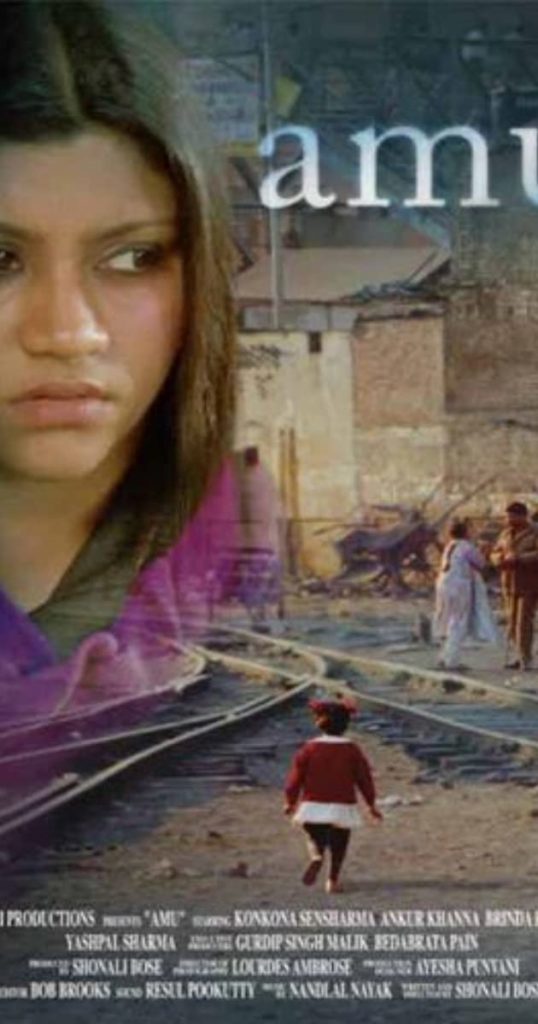

Soumya reviews a film, Amu, on Sikh genocide and recalls his days as a volunteer. The reel and the real crisscross, grotesquely. The horrors come alive. An exclusive for Different Truths.

I finally got to see Shonali Bose’s acclaimed film Amu, on the Sikh genocide, of 1984, in Delhi, on the channel Mubi, meant for art-house cinema. The film’s commercial release had gone in the blink of an eye, and if it was available on television or OTT platforms, it had evaded my searches. As it was a very well made, sensitive and powerful film, I wonder whether this obscurity was deliberate, as there was a clear indictment of the ruling government of the time, and the ruling party.

The film traces the attempt of an adopted child from the US to trace her roots in Delhi and accidentally unearthing the fact that she was an orphan of the organised anti-Sikh pogrom of 1984…

The film traces the attempt of an adopted child from the US to trace her roots in Delhi and accidentally unearthing the fact that she was an orphan of the organised anti-Sikh pogrom of 1984, which too has been forgotten since, and the culprits who conducted the massacres remained free and in power.

The film released a flood of memories, as I was an eyewitness to those riots, had seen them up close, and it had deeply affected me. I had been a young idealistic chap then and dating a young Sikh lady, who subsequently was to be my wife, and I had never witnessed such horror from a close-up. So, it had such an impact I suppose.

I and my friends tried to rescue a fleeing Sikh family and find them shelter somewhere, and everybody seemed too terrified to help…

I and my friends tried to rescue a fleeing Sikh family and find them shelter somewhere, and everybody seemed too terrified to help, while the police told us to mind our own business, till we could get them to a relief camp. This put me in touch with a volunteer group, who were carrying out relief work and I volunteered immediately.

I was put in a group trying to trace missing people and reunite families separated by the turmoil. Our group was a mixed bag, a renowned economist, a well-known TV anchor, couple of LSR students from the hostel and me. We visited the various camps and the worst affected areas to try and locate missing people.

Constant exposure to horror numbs the mind, but certain scenes scar our souls and cannot be forgotten.

One was a surreal scene of a guy looking like a villain from a second-rate Bollywood film running holding a life-size doll of a girl, upside down, by its legs, looking as if he is carrying a dead child he just killed.

But the most horrifying one was of a lady sitting silently, staring blankly at nothing. She would not respond to anything or bother to eat or wash.

One was a little girl asking if we could find the book she was reading, as she was mid-way through. But the most horrifying one was of a lady sitting silently, staring blankly at nothing. She would not respond to anything or bother to eat or wash. She had seen her family burnt alive.

Seeing Amu’s mother in the film reminded me of her. Other incidents that remain are less grim.

One was a foreign news channel shooting the incidents by having some locals acting out the roles of looters. We pointed this out to the survivors in the camp. Furious that the real images of the ruling party leaders leading marauding mobs with voter’s lists to identify Sikhs were not being shown, they chased away the crew, who ran like the wind back to their safe air-conditioned hotels.

Narula’s, a popular fast-food chain owned by a Sikh family, had kept the kitchen open and was providing food to us relief workers.

Narula’s, a popular fast-food chain owned by a Sikh family, had kept the kitchen open and was providing food to us relief workers. But the gurdwara, which was doubling as a relief camp insisted that we eat at the langar, or community kitchen, which is also considered Prasad, or blessings of God. So, we reluctantly had to eat that bland fare, while pining away for the pizzas, steaks, and burgers waiting for us.

The economist who led our group had been a professor at the Delhi School of Economics from where I had just graduated. I introduced myself as his student who had not met him as I rarely attended classes. He embarrassed me by disclosing that he knew me by my notoriety and proceeded to regale the others with exaggerated accounts of my misadventures, which included allegedly gate crashing the dean’s daughter’s wedding party.

Another less pleasant memory is calling the lady I was dating to check if they were okay and having her brother reply, “still alive”.

Another less pleasant memory is calling the lady I was dating to check if they were okay and having her brother reply, “still alive”. One of her relatives was missing and we later confirmed that he too was murdered, as were most of the missing people we tried to locate.

The party that carried out the massacres is no longer in power, but public memory is short, and most of the perpetrators are still at large, though some had to retire from public life, and only a few foot soldiers were given token punishment.

We require films like this to keep the memory alive, as otherwise, we keep repeating such shameful episodes of our history.

Visuals by Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By