It is no surprise that the two poets would each write a poem on, and titled Africa, voicing their protest against exploitation of Africa and its inhabitants by powers superior. Africa, by Blake, is an epic poem, the first section of one of his prophetic books, The Song of Los (1795), the second section being titled Asia. While Blake’s poem was composed during one of the most turbulent times in European history, the French Revolution, Rabindranath Tagore wrote his poem Africa, during the Second World War. Tagore wrote the poem originally in Bengali, later translated by William Radice. Dr. Madhumita compares and critiques the two great poets, in her erudite research paper. A Different Truths exclusive.

Scientists believe human beings originated in Africa. And it is Africa that has been one of the most exploited countries in the world. Poets from across the world have written on the misfortunes of the people of Africa through the ages. A study of two poems by two stalwart poets, living and writing in continents far away from Africa, seems relevant and worthwhile.

Scientists believe human beings originated in Africa. And it is Africa that has been one of the most exploited countries in the world. Poets from across the world have written on the misfortunes of the people of Africa through the ages. A study of two poems by two stalwart poets, living and writing in continents far away from Africa, seems relevant and worthwhile.

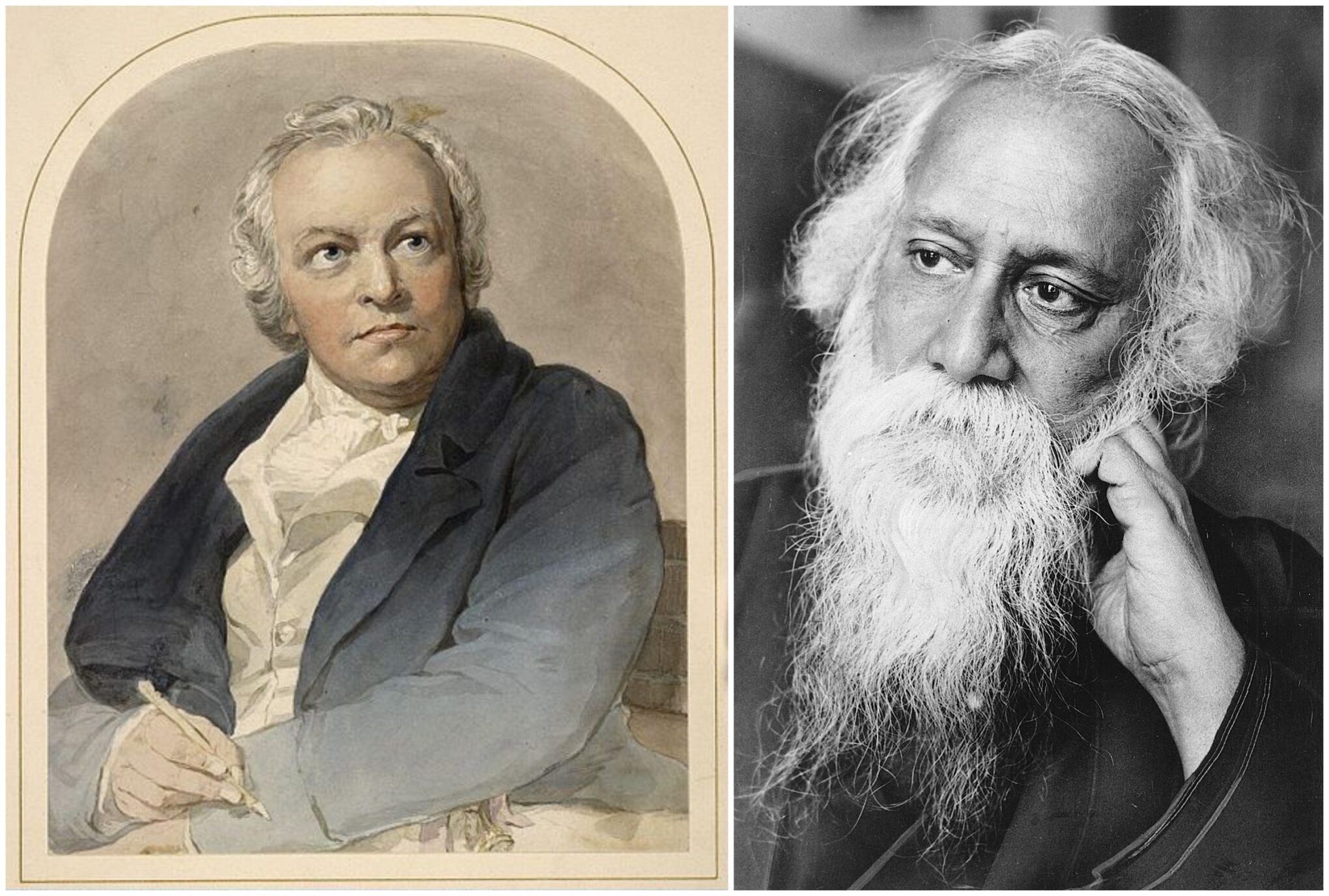

The two poets lived thousands of miles and a century apart. One belonged to a poor family, the eldest son of a hosier in London. The other hailed from a blue-blooded family in India, the youngest son of a wealthy, cultured, illustrious father. Yet they had a lot in common.

The two poets lived thousands of miles and a century apart. One belonged to a poor family, the eldest son of a hosier in London. The other hailed from a blue-blooded family in India, the youngest son of a wealthy, cultured, illustrious father. Yet they had a lot in common. Both William Blake (1757-1827) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) were multi-faceted artists who not only wrote in verse and prose but were well-known painters too. They were ‘

myriad- minded’ men who shared a common platform; they lived and wrote during the two most crucial periods in world history. While the late eighteenth century saw one of the greatest revolutions till date and the rise of industrialism and capitalism, identified early by the visionary Blake as a terrifying future threat to humanity, the era in which Tagore lived witnessed two world wars; the steep ascent of capitalism and mechanisation, the staggering fall of humanity into its clutches, and, colonization. The two sensitive minds reacted to their environment in much the same way, voicing their alarm and disapproval in their writings and drawings, their creative output in general being a critique of contemporary global society. They did not confine themselves to their country and nation, both expressing grave concern for the future of humanity. Both were believers in the Religion of Man, their hearts bleeding for the rights and the well-being of the common, exploited Man. And both were Romantic poets. Imagination, the most significant feature of Romanticism, particularly in its utopian revolutionary spirit, seems to occupy the foremost position in the ideology of both Blake and Tagore.

Neither having gone through formal education, they were both well-read in literature and philosophy. While Tagore’s admiration of the English romantic poets, particularly Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats, is today known to all, there seems to be hardly any Tagore critic mentioning Blake with reference to Tagore. Yeats was the first to compare Tagore to Blake in his introduction to the English Gitanjali. Tagore himself seems nowhere to have mentioned Blake. But that he had read Blake and admired the English visionary poet’s creative genius is clear from his essay ‘Religion of an Artist’ (a lecture delivered at the University of Dacca in 1926).[1]

Speaking of poetry as being ‘a creation of a uniquely personal and yet universal character’, Tagore quotes a poem of Blake as an illustration for his argument.

Speaking of poetry as being ‘a creation of a uniquely personal and yet universal character’, Tagore quotes a poem of Blake as an illustration for his argument. It is interesting to note here that Tagore quotes not from a well-known poem of Blake but from a lesser known fragment from his Notebook, ‘Never seek to tell thy love’, preferring the deleted word ‘seek’ to Blake’s final choice ‘pain’.[2] Both Blake and Tagore believed in the human imagination as a creative force, and thus divine. They were both advocates of energy and freedom of mind and spirit and vehemently opposed impositions and restrictions of all kinds. They saw society as an all-imposing, restricting factor, binding the free human spirit in bonds of systematised rules and regulations. William Blake began with the concerns of England and her men. He went on to explore Europe, America, Asia, Africa, and finally into the soul of man, for the history of the individual is but a scaled-down version of the history of the universe. His thoughts culminate in The Four Zoas, his magnum opus where he narrates the story of the fall of the Eternal Man and his  redemption. Man, now fallen into disunity may only be redeemed if the ‘four mighty ones’ in him – Reason, Wisdom, Love, and Imagination – are reunited in harmony.

redemption. Man, now fallen into disunity may only be redeemed if the ‘four mighty ones’ in him – Reason, Wisdom, Love, and Imagination – are reunited in harmony.

While in Munich, in 1930, Tagore wrote a long prose-poem The Child, inspired by a passion-play, on the birth of Christ that he had seen enacted in the village of Oberammergau. Published the following year in London, this is his only major poem written originally in English, later translated into Bengali as ‘Sishutirtha’ in 1932, included in Punascha. The poem, epical in its grand style, proclaims Tagore’s ultimate faith in man. A few months after the composition of the poem, in December 1930, Tagore said in a lecture addressed in New York: ‘The babe who was born centuries ago, brought exaltation to man. Not machinery, not associations, not organizations, but a human babe, and people were amazed. And when all the machinery will be rusted, he will live.’[3]

A few months after ‘Sishutirtha’ was published in the monthly magazine Bichitra, Tagore wrote in a commentary on the poem on the dual nature of man, the beastly and the divine. The beast in him rules when he is possessed by his greed for material gains, his pride in power and his delirious obsession with reason and intellect, and humanity is threatened. Salvation comes to man in this crisis in the form of the eternal man – ‘sanatan manab’ – who is reborn again and again. Like Blake, Tagore believed in a future golden age when the ‘mahamanab’ will be born, a distant future when man will have conquered his animal nature.

It is thus no surprise that the two poets would each write a poem on, and titled Africa, voicing their protest against exploitation of Africa and its inhabitants by powers superior.

It is thus no surprise that the two poets would each write a poem on, and titled Africa, voicing their protest against exploitation of Africa and its inhabitants by powers superior. Africa, by Blake, is an epic poem, the first section of one of his prophetic books, The Song of Los (1795), the second section being titled Asia. In the first section, Blake speaks of thedecline of morality in Europe, which he blames on both the African slave trade and the enlightenment philosophers. Blake illustrated his books by etching the designs on copper plates, himself. The Song of Los was one of the few works that Blake describes as ‘illuminated printing’, and the title page has the image of an old man in an empty, dead world, looking on at the title of the work.

The poem begins with a commentary by a human singer presenting to mortal listeners, a song which Los sang to his fellow Eternals. Los is the Eternal Prophet or Imagination, a creative force. He participates in world events as an artist, by singing of a relationship between the revolution and the two continents, Africa and Asia, which have not yet been directly affected by the rise of Orc, the spirit of fiery revolution in Blake’s mythological order.[5] Orc, the son of Los and Enitharmon, Los’ female emanation, is for Blake, the fiery spirit of Revolution. He is described as a pillar of fire that burns oppression away. Orc fights against Urizen’s rationality, and seeks to free people.[6]

I will sing you a song of Los, the Eternal Prophet:

He sung it to four harps at the tables of Eternity.

In heart-formed Africa.

Urizen faded! Ariston shudderd!

And thus the Song began:

In Africa, Los sings of Adam, Noah, and Moses and how they were granted laws by Urizen, a bearded old man who represents Reason in Blake’s personal mythology.

In Africa, Los sings of Adam, Noah, and Moses and how they were granted laws by Urizen, a bearded old man who represents Reason in Blake’s personal mythology. Abstractions were granted to Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato, the gospel being given to Jesus, ‘a loose Bible for Mahomet,’ and a book on war given to Odin. These, according to Blake, caused misery to Man, as they were chains that bound the mind:7 Only six copies of the work survived, and the work was not listed along with Blake’s other works that he sold in either 1818 or 1827. There were no mentions of the work by either Blake’s contemporaries or his early biographer Alexander Gilchrist. But The Song of Los is connected to both America and Europe, Blake’s other prophetic books, the three works being united by the same historical and social themes. Africa summarises Blake’s historical cycles, which describes a three-part tyrannous power of Egypt, Babylon and Rome. Jon Mee claims that “Nowhere is Blake’s interest in comparative religion more obvious than in The Song of Los.”8

In The Song of Los, Blake condenses the history of religion, but does so in a non-chronological manner. His history relies on Urizen to establish the various historical moments as incidents, and the type of order within the poem is similar to the prophetic narrative.[9] The prophetic image is also embodied within the work by Los, who, when he submits to the system created by Urizen, loses his prophetic ability. In addition to the prophetic aspects, the work deals with religion as a whole. The first section describes the origin of priest-craft and the origins of religion, which is established through a bardic form of poetry.[10]

“…These were the Churches; Hospitals: Castles: Palaces;

Like nets & gins & traps to catch the joys of Eternity

And all the rest a desart;

Till like a dream Eternity was obliterated & erased.”

In locating his allegorical universe in Africa, Blake emphasises on the Beginnings; the origin of humanity and then the beginning of slavery, of religion and of laws, both of which restrain and restrict and, exploit.

Africa is the perfect symbol of human degradation and misery not only because of its association with slavery down the ages, and contemporary trafficking of black people, but also for Egypt being the place of biblical place of bondage for the Jews.

“The Guardian Prince of Albion burns in his nightly tent.” That the concluding line  of Africa is identical with the opening line of America, another prophetic book, suggests that ‘the tyranny of these corrupt and binding institutions has made inevitable a world-wide revolution in which the people of Africa will be liberated.’ Africa is the perfect symbol of human degradation and misery not only because of its association with slavery down the ages, and contemporary trafficking of black people, but also for Egypt being the place of biblical place of bondage for the Jews. [11]

of Africa is identical with the opening line of America, another prophetic book, suggests that ‘the tyranny of these corrupt and binding institutions has made inevitable a world-wide revolution in which the people of Africa will be liberated.’ Africa is the perfect symbol of human degradation and misery not only because of its association with slavery down the ages, and contemporary trafficking of black people, but also for Egypt being the place of biblical place of bondage for the Jews. [11]

While Blake’s poem was composed during one of the most turbulent times in European history, the French Revolution, Rabindranath Tagore wrote his poem Africa, during the Second World War. Tagore wrote the poem originally in Bengali, later translated by William Radice. The poem has more than one version. While it was first published in Prabasi in 1936, Tagore republished it in Patraput in 1937 and added a later and final version, published in Viswabharati Patrika in 1944. Provoked by Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, Tagore wrote Africa, the only one he has written on the continent. On the request of an African prince who was then in Oxford, Tagore had translated the poem, the translation being published in theSpectator. The poem is a sharp critique of British imperialism, and Tagore presents a distinct contrast between the pre and post-colonised state of Africa. The poem, however, is more about Tagore’s view of modern civilization as a form of savagery than about Africa the continent. The last stanza of Tagore’s own translation of the poem is quoted here.

Today, when on the western horizon

The sunset sky is stifled with dust-storm,

When the beast, creeping out of its dark den

Proclaims the death of the day with ghastly howls,

Come, you poet of the fatal hour,

Stand in the dying light before nightfall,

At the door of that ravished woman

And beg her, ‘Forgive, forgive.’

In the midst of violent delirium,

Let that be your civilisation’s last great word.[12]

With his nationalistic attitude, Tagore identified British imperialism as a manifestation of a social disease, destroying traditional culture, despoiling the country, robbing it of its richness and its natural treasures…

With his nationalistic attitude, Tagore identified British imperialism as a manifestation of a social disease, destroying traditional culture, despoiling the country, robbing it of its richness and its natural treasures and hindering the country’s progression towards civilisation.

‘Inspired by the forest

You went on to celebrate life

Very like the forests,

Unfettered,

An array of myriad colours,

Complexities arisen with ease.’[13]

This was Africa, or for that matter any independent country, rich in its inherent beauty and power. Immediately after Tagore speaks of ‘continents far away’ where with ‘Each new rising day’

‘On the lofty mountain peaks of the human mind’

‘The history of ravage

Was being written all of a sudden in creation and cataclysm.’

‘Arrogant Europe

Had barged onto your courtyard without a light

In the guise of plunderers—

Had ridden the chariot across your bosom,’ and Africa was shrouded in a shadow, the black veil of tyranny rendering the continent

a stranger to her neighbour.

The humanisation of Africa adds a pathos which is pronounced in the last stanza where the continent is seen as an ‘ever-exploited Woman…the insulted one.’ As a fellow human, Tagore suggests that the sin of the tyrannical coloniser is our sin too. And the only redemption for the repentant man would be to ask for her forgiveness. The last line suggests a corrected vision and a step taken towards undoing of the ills of the past.

Tagore had told the African prince for whom he had translated the poem: “I shall feel richly compensated if I know it will reach my friends in Africa and let them realise how an Indian poet feels about the despoliation of a whole continent in the name of civilisation.”[14]

Notes and References

- ‘The Religion of an Artist’, ed: Sisir K.Das, English Writings of R Tagore, Vol.3, Sahitya Akademi, pp.695-96

- Keynes Geoffrey ed: Blake Complete Writings, London 1966 p.161

- Lecture delivered at New York on December 1,1930, published in The Modern Review, July 1931, p.48, quoted in Rabindra Rachanabali, Viswabharati, 1986, vol.viii, p.712

- Commentary on Sishutirtha published in Bichitra, Ashwin 1338 B.S.pp.285-86, extract reproduced in R.R. vol.viii, pp.712-13

- Johnson Mary Lynn and Grant John E, ed: Blake’s Poetry and Designs, W.W.Norton & Company, New York, 1979

- Mee, Jon. Dangerous Enthusiasm. Oxford: Clarendon, 2002, pp.83-84

- Bentley, G. E. (Jr). The Stranger from Paradise. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.pp.154-55

- Mee, Jon. op.cit. p.122

- ibid pp. 24–25

- ibid pp. 104, 122–123

- Johnson & Grant, op.cit. p. 134

- Krishna Dutta & Andrew Robinson, Rabindranath Tagore, Boomsbury Publishing, UK, 1997, p.345

- ‘Africa’, Patraput, Rabindra Rachanabali, Viswabharati, vol.10, pp.664-65 [Translations of all quotations henceforth from the original Bengali poem are mine. The translated full poem is included as Appendix to this article]

- Dutta & Robinson, op. cit. p.345

Appendix

Africa

Rabindranath Tagore

I

In the frantic bewildered primordial age

The wrathful arms of the ocean

Severed the link

And carried you away from the bosom of the Eastern Earth

O Africa,

Kept you in exile in the darkness of the impenetrable forests.

In the dense forest enclosed with shrubs and creepers

You tried to find your way

Your sharp penetrating eyes tearing the darkness apart;

You mocked the formidable

By rendering yourself ugly—

Chanting the mantra to overcome fear

You bestowed upon yourself the grace of the fearsome

By beating the drums of a frenzied dance.

Inspired by the forest

You went on to celebrate life

Very like the forests,

Unfettered,

An array of myriad colours,

Complexities arisen with ease.

In the continents far away

There rose that day

Reverberating deep sounds of new maxims

Each new rising day

On the lofty mountain peaks of the human mind.

The history of ravage

Was being written all of a sudden in creation and cataclysm;

On the graves of a civilization going repeatedly into oblivion,

lying deep in the bosom of earth,

there rose suddenly the audacious flag of blossoming power.

Like the days of the beginning of Creation

When darkness remains in a stunned silence

With the embryonic sun and stars in its womb

You remained in seclusion

In a similar dense darkness

Within the Earthly temple of meditation.

All the mysteries stored in the treasury of darkness

The unreachable, the untouched,

You sought to seek.

The charms of the magical Nature

You were learning to entrap with your senses.

Shrouded in a shadow O Africa,

Veiled in black

You were a stranger to your neighbor.

Arrogant Europe

Had barged onto your courtyard without a light

In the guise of plunderers—

Had ridden the chariot across your bosom,

There, where the sorrowed human heart

Was spread across the green leafy shade.

The savage greed of the civilized had rendered naked in the darkness

The shameless inhumaneness.

Tears mingled with your blood

Had rendered the path of silent cries slippery—

The unholy mud trampled upon by boots barbaric

Has left an indelible mark on your history of misfortune.

Then at the same time in their land

Bells rang in the name of the kind Lord in churches

In the morning and evening,

Children played in their mothers’ laps,

The poets sang paeans to beauty.

Behold today, in the west,

There rises a storm, thunder rolls

In the dust laden sky

The day seems to come to an end.

The animals rise in their secret lairs—

They claw away; tear apart the treasured cover of their land,

Laying bare the dust.

Come, the last poet of the dark era—

In the darkness of self-abhorrence of this impending evening

Come to the ever-exploited Woman,

Stand at the door of the insulted one

And seek forgiveness.

May it be in the midst of your wild delirium of your brutal civilisation

The last word holy.

(Translation: Dr. Madhumita Ghosh)

©Dr. Madhumita Ghosh

Photos from the Internet

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

The much awaited article finally arrived today. Thank you providing the article during the unsettling times which brings serenity to a worried heart and head.

Best regards

Sincerely