Abu portrays a group of poor passengers in a shared auto and a haughty rich woman, on a cold Sunday evening, in this short story. An exclusive for Different Truths.

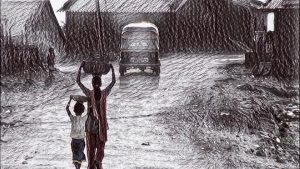

It was a December Sunday evening, foggy, chilly, and bitter. Air was biting hard, and yonder Jaldapara forest, famous for its one-horned rhinos, lay asleep under the quilt of dew. I visited a village, enjoyed daylong the beauty of the forest. Fatigued, in the evening I came back to Galakata haat, adjacent to the forest, drank tea at a crowded shop, made a round around the haat, and surveyed peasant men and women selling and buying grocery, vegetables, fish. Some were burning woods, some smoking, chatting, drinking tea, and abusing the harsh day. Next, I waited for an auto to return home at Falakata.

It was a December Sunday evening, foggy, chilly, and bitter. Air was biting hard, and yonder Jaldapara forest, famous for its one-horned rhinos, lay asleep under the quilt of dew. I visited a village, enjoyed daylong the beauty of the forest. Fatigued, in the evening I came back to Galakata haat, adjacent to the forest, drank tea at a crowded shop, made a round around the haat, and surveyed peasant men and women selling and buying grocery, vegetables, fish. Some were burning woods, some smoking, chatting, drinking tea, and abusing the harsh day. Next, I waited for an auto to return home at Falakata.

Ten minutes passed. My sweater was soggy with dripping dew. I looked at sides and waited anxiously. Just then an auto jerkily stopped before me. It was almost full.

An Adivasi peasant woman with her half-naked child was stealthily dozing off. Next to her haughtily sat a wealthy, educated lady whose child, bundled with woolen clothes and all, was snoring peacefully at her lap.

An Adivasi peasant woman with her half-naked child was stealthily dozing off. Next to her haughtily sat a wealthy, educated lady whose child, bundled with woolen clothes and all, was snoring peacefully at her lap. Auto was running fast, street empty, icy air fiercely kicking and slapping us.

A tiny timorous bulb was dangling overhead. Its light was hazy and could hardly make us visible to one another.

Suddenly at the whisk of a wind, the woolen cap slipped a bit out of the child’s head. And the panicky rich mother shouted, “Driver, driver, stop.”

“What, madam?” warily asked the driver.

“Stop. My heart will catch cold, her head is bare,” she hastily said and began to adjust the beautifully designed cap on her sleeping child.

The auto stopped with a hitch. Passengers, aged men and women, were shaken to the bone, looked red and abused the driver by calling his father’s and grandfather’s names.

The auto stopped with a hitch. Passengers, aged men and women, were shaken to the bone, looked red and abused the driver by calling his father’s and grandfather’s names.

The child’s head was fully covered. The rich mother was at ease. She randomly kissed the child, repeatedly examined her darling’s socks and gloves, and as an extra protective measure tightly covered her with the red Kashmiri shawl she wore. Satisfied finally, she ordered the driver to move.

The sky was dull. Surroundings were foggy. Not a soul on the street was visible. Not a dog was barking or a bird calling or a child crying. It was a gloomy, cheerless evening. The only solace I had was to watch the leaping fires at the yards of the sleepy houses. Peasants sat on their haunches around the fires and baked limbs before retiring to bed.

Passengers called the driver to run slow, but he hardly paid ears to his daily passengers. They were uncouth, boorish, lowly weaklings —masons, daily labourers, carpenters, fish sellers, paan sellers, vegetable sellers, umbrella repair men, wood cutters and the like.

Again, the wind began biting hard. Passengers called the driver to run slow, but he  hardly paid ears to his daily passengers. They were uncouth, boorish, lowly weaklings —masons, daily labourers, carpenters, fish sellers, paan sellers, vegetable sellers, umbrella repair men, wood cutters and the like. It was a regular affair, and he was dead with such complaints, requests, and demands from these poor sops.

hardly paid ears to his daily passengers. They were uncouth, boorish, lowly weaklings —masons, daily labourers, carpenters, fish sellers, paan sellers, vegetable sellers, umbrella repair men, wood cutters and the like. It was a regular affair, and he was dead with such complaints, requests, and demands from these poor sops.

Hardly a stop was crossed, the rich woman again shouted and the driver again stopped with a sudden brake. The passengers were thrown out of their seats, and this time they abused the driver with more vehemence. It, however, hardly moved the driver. He was nonchalant. His face was vacant.

“What madam?” asked the driver while painstakingly combing his bald head in the cracked rear mirror.

“I want an extra seat. I’ll pay for it. I cannot go home like this. Such poor things! Rotten! ” fumed the lady.

“Why, madam? Any problem?” casually he asked.

“I want another seat. I’ll pay you,” with a reproachful look she asserted.

The driver sensed a trouble. He scratched his head, squinted eyes, and made his mind with the flash of a light.

The driver sensed a trouble. He scratched his head, squinted eyes, and made his mind with the flash of a light. “A rich lady! She must be served. Regulars could be managed. They would howl and growl and be silent soon. But the lady…” thought the driver himself. But he feigned.

“Where can I have extra seat, madam? It’s packed like a tin of sardines. Please bear trouble a while. In the next stop it will be empty as a frozen field.”

Passengers were annoyed. After the day’s gruelling work they were hungry for home. But how could they argue with a sophisticated lady? So they furtively exchanged glances and stayed resigned to their posts.

Passengers were annoyed. After the day’s gruelling work they were hungry for home. But how could they argue with a sophisticated lady? So they furtively exchanged glances

“Do you offer an extra seat or not? I’ll buy it. It’s simple. Okay, it’ll not work. I’m calling my husband. Do you know my husband? He is a BSF officer, posted at Chengrabandah border,” warned the irate lady, and she fumbled her lather satchel for her android set.

“Madam, please stop. I’ll be ruined. I manage. One minute please,” pleaded the driver with folded hands. His face was pale, and his legs stirring. Beads of sweat decked his temple. He behaved as if a fire caught him.

“Hey! Filthy fellows, move, keep legs pressed, hands tight….Madam, please,” apologetically the driver said. “Hey! Sukhi. Make a room for madam. Move to extreme left,” hollered the driver.

Bare footed Sukhi had no woolen clothes, no cotton chadar either. Her child had a running nose, a pale whitish face and dry limbs. She was shivering. Her child, like a dead piece of flesh, lay pasted to her dry breast.

Bare footed Sukhi had no woolen clothes, no cotton chadar either. Her child had a running nose, a pale whitish face and dry limbs. She was shivering. Her child, like a dead piece of flesh, lay pasted to her dry breast.

Bare footed Sukhi had no woolen clothes, no cotton chadar either. Her child had a running nose, a pale whitish face and dry limbs. She was shivering. Her child, like a dead piece of flesh, lay pasted to her dry breast.

Sukhi moved to the extreme left without a word. She bore no grudge against the driver. It was a daily affair. She worked in a tea garden, ten miles away from her hut. Her husband was an idle drunkard. Last year, he died of liver ailment.

“Hey, old haggard! Move to right end. It’s not a private car,” blasted the driver pouring a packet of gutka into his mouth.

An aged man was sized to the far right. The lady took her extra seat and smiled a victory.

The auto ran again. The icy wind slapped us fiercely. Sukhi chattered, and her little messy piece of flesh lay cuddled to her breast as a log of dry wood.

Photo from the Internet

By

By

By

By