Shyamal tells us about the Kantha of Bengal. Its utilitarian aspect for a newborn in a family but also how it acquired the status of high art but is it helping the true artisans, he asks. An exclusive for Different Truths.

The arrival of a new baby is always a matter of rejoicing for the family anytime anywhere. In a Bengali household, the natal paraphernalia usually commences as early as a year prior to the actual delivery of the newborn; it begins when elderly ladies initiate a process of making Kantha to be used for and by the new baby. So goes a saying, that there is no Bengali who has not been wrapped in infancy with Kantha.

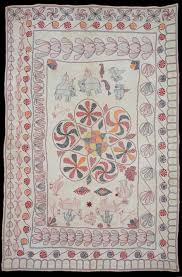

Kantha (in a rustic language called as ‘Tena’) may be most closely described as layers of patched old clothes stitched with a pattern of stitching called as ‘running stitch’ exclusively by the respective household ladies. The making of a Kantha or the art of stitching has remained an ethnic household art of Bengal, including Bangladesh, and parts of eastern India viz. Odisha and Assam.

Kantha (in a rustic language called as ‘Tena’) may be most closely described as layers of patched old clothes stitched with a pattern of stitching called as ‘running stitch’ exclusively by the respective household ladies. The making of a Kantha or the art of stitching has remained an ethnic household art of Bengal, including Bangladesh, and parts of eastern India viz. Odisha and Assam. The stitching of Kantha has been a unique traditional process of reusing old, torn or unusable clothes of the house like saree, dhoti etc. Significantly, the use of base cloth pieces beholds not only the antiquity from third or even fourth generations but also the warmth of ancestral blessings with a stitched Kantha for a newborn child. This X-factor will always be unique in the making of it.

As a practice, old, used sarees are never discarded but preserved with the sole motive of stitching Kantha for any would-be born baby in the house, even at times given to relative or a neighbour`s house as a gift. Normally, stitching is done on layers and pieces of old clothes stitched together with ‘run stitch’ on all sides leaving the centre for non-delicate motif or design; but many a veteran expert ladies would prefer curved stitches and needleworks depicting a nice and eye-catching flower, plants or motifs. Gradually the primary stitch works to be used as Baby Kantha improvised into needlecraft of ‘Nakshi Kantha’. By the way, the preparatory essentials remain the same – thread rolls are prepared by extracting thread lines from the saree borders, to add more colours additional borders would be extracted; to make Kantha puffy more layers of sarees are used. Though this was deemed to be a household craft, a beautiful decorative piece may take months to finish, hence the urgency to begin Kantha stitching, calculating the arrival date of newborn. The illiterate or not so knowledgeable ladies traditionally has been aware of soft support needed to the newborn, that`s why old clothes have always been preserved in Bengali households.

Although the art has two primary styles – Kantha for newborns and the other ‘Nakshi’ for multipurpose uses; the Nakshi gradually has evolved into long quilt type covers to be used during light cold by all. Different patterns of stitching also have come to stay.

Although the art has two primary styles – Kantha for newborns and the other  ‘Nakshi’ for multipurpose uses; the Nakshi gradually has evolved into long quilt type covers to be used during light cold by all. Different patterns of stitching also have come to stay. Bangladesh remains the harbinger for the improvisation, improvement and aesthetics in the traditional art of Kantha stitching.

‘Nakshi’ for multipurpose uses; the Nakshi gradually has evolved into long quilt type covers to be used during light cold by all. Different patterns of stitching also have come to stay. Bangladesh remains the harbinger for the improvisation, improvement and aesthetics in the traditional art of Kantha stitching.

To trace the ethnicity of this art, the scholars in Bengal referred to the mention of this form in Chaitanya Charitamrit by Krishnadas, nearly 400 years old.

With the passage of time and urbanisation, like much other ethnic art and craft, the art of Kantha stitching in the individual house domain slowly has begun dying out due to disinterest or disinclination of current home keepers. An exception has been for ‘Nakshi Kantha’ popular and widely made in parts of Bangladesh,

Since 2008, an official encouragement helped to safe keep some exquisite pieces of Kantha in the gallery of Indian museum, Kolkata and National Craft Museum, Delhi.

As government initiative to protect and promote this ethnic art has been taking shape, commercial hawks have also put eyes on minting money through reinventing Kantha patches or Nakshi art as designer motifs on saree, apparels or other garments.

As government initiative to protect and promote this ethnic art has been taking shape, commercial hawks have also put eyes on minting money through reinventing Kantha patches or Nakshi art as designer motifs on saree, apparels or other garments. It would not have mattered, had these art promoters helped to encourage the household craftsmen/women; instead of promoting these commercial entities have created travesty of this artwork in the name of promotion and profit. It’s a sad facade of an almost extinguished art of household tradition of stitching Kantha. Now, what we come across at Malls, shows or high-end markets as Nakshi Kantha style sarees or kurtas are plagiarised or imitation version of our original ethnic creations. If we desire and look into our own heritage, we may find a way for the revival of the Kantha – a labour of love always.

Photos by the author

By

By

By

By

By

By