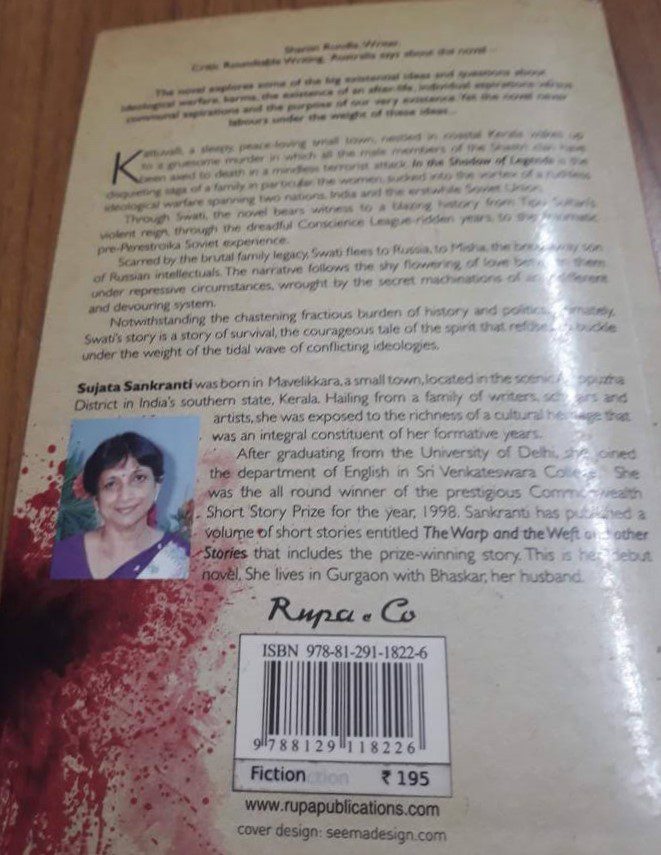

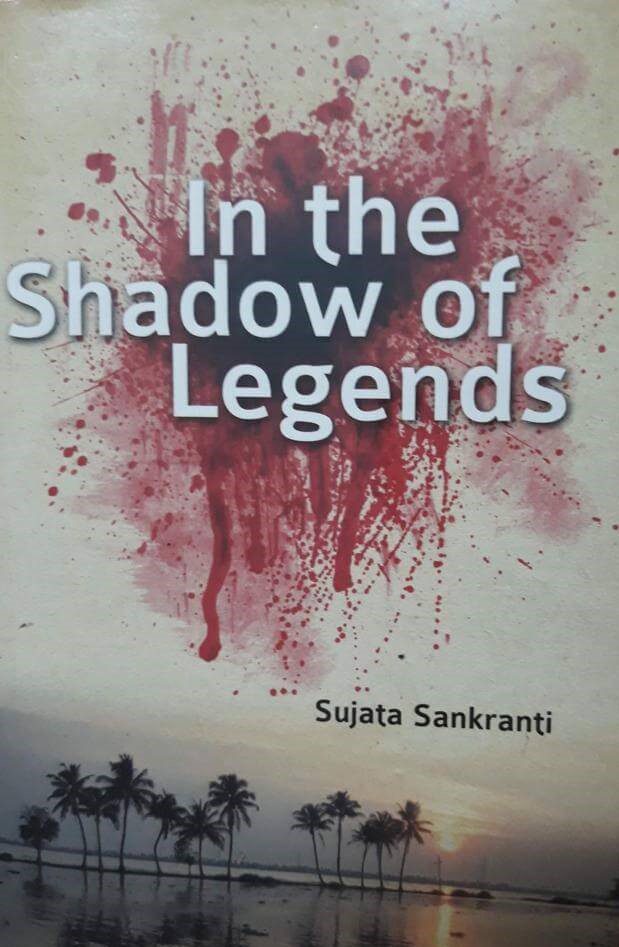

Dr. Roopali reviews Sujata Sankranti’s debut novel, In the Shadow of Legends, that explores an unjust and harsh feudal system, love, loss, rape and murders with subtility and grace. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Sujata Sankranti’s debut novel In the Shadow of Legends is a riveting narrative of a genteel family from Kuttapalli, in Kerala.

The female protagonist Swati takes us into a sleepy town called Kuttapalli. A town that wakes up to the brutal murder of the male members of the Shastri family. The simmering underbelly of a disgruntled left-behind people. People deprived of their land and fundamental rights by a visible and harsh feudal system.

It now rears its ugly head. The slogan, ‘Justice for All’, fills the air and graffiti. Justice for all those who have been quietly and openly exploited. Women too. The communist political upheaval violently uproots the Shastri family, casting a dark shadow on their lives.

The female protagonist Swati takes us into a sleepy town called Kuttapalli.

Kerala to the Soviet Union

The second half of the story moves from lush Kerala in India to Moscow and Leningrad in the Soviet Union. The author, who is from Kerala’s elite families, lived in the Soviet Union for several years. The novel is thus a well-researched and authentic piece of literary work.

Sankranti’s strength as a storyteller is clearly seen in the novel.

Sankranti’s strength as a storyteller is clearly seen in the novel. A Commonwealth Short Story Prize Winner, she writes with immense subtlety and grace.

God’s own country Kerala and its many cultural skins peel slowly before our eyes. The Russian Matryoshka nesting doll with its many layers is a trope in the narrative. Kerala’s cultural and subaltern life interweaves to create a tapestry that is colourful, fascinating and real.

The first chapter establishes the flavour of a multi-faith society.

The first chapter establishes the flavour of a multi-faith society. Joseph, who is a frequent visitor to the house is learning Sanskrit. The Christmas Cake is a telling metaphor. Joseph takes great care not to step on the Kolam rice powder patterns on the porch of a Hindu household drawn by its women. This little detail points to the respect and reverence enjoyed between communities in India. Stories of Santa Claus narrated by young Swati are laughed away by a rational Joseph.

“On Eid soon after sighting the moon Ravuthar would visit us….” Hindus and Muslims and Christians live in peace. Once, not long ago they were tenants on the Shastri estates. Influenced by Mahatma Gandhi and Vinoba Bhave, Shastri ‘freed’ them from their tenancy. The land was given away in the Bhoo Daan movement. Giving way to an equitable and peaceful relationship. But feudalism had created a divisive social fabric.

Disruptive Happenings

The appearance of the feudal and entrepreneurial maternal uncle Vishnu sets the stage for the disruptive happenings in an otherwise happy household. His proprietorial claim as son-in-law creates further upheavals in the family. This, in turn, has a long-lasting impact on familial and social relationships. Exploitative and harsh, he is a contrast to the gentle Gandhian, Shastri.

Sankranti sets the stage at the outset for us to for us to understand why and how things change.

Sankranti sets the stage at the outset for us to for us to understand why and how things change. She finely defines the relationship between each of the characters. She leaves out no details, and we find ourselves in an intimate partnership with the Shastri household. We are also active participants in religious processions, illicit affairs, and even a diabolic conspiracy! The reader is deeply moved at different levels. Such is the power of her words.

The story moves forward spinning a web of tragic circumstances. The Shastris are not a part of a slow decadent world where nobility and fortunes are on the wane. It is a cataclysmic end. Sankranti draws on a real-life incident.

The violence is perpetrated with the active help of Janardhan, an unacknowledged member of the Shastri lineage.

The violence is perpetrated with the active help of Janardhan, an unacknowledged member of the Shastri lineage. His reason being his deep unreciprocated attachment to the rebellious Mini.

Pathos and Sadness

Tremendous pathos and sadness hang low and palpable throughout. But humorous details, satire and real life snippets keep the story moving. The cinematic effects are abundant. Sepia colours, black and white montages, and technicolour collages. All constantly emerging and reemerging.

The women in the Shastri family are exceptional.

The women in the Shastri family are exceptional. They are traditional and respectful of their elders with a strong mind of their own. Fearless and caring, they grow up among books and discourse. The learned head of the household, and the library of books enrich their minds. Slowly and imperceptibly political changes begin to change the minds of the members of the family.

The feudal structure finds visible resistance. Mrinalini or Mini as she is known, openly resists customary marriage to the maternal uncle. She talks of justice and the right to free thinking. Cutting off her hair to defeminise herself is her open act of defiance. Her path is uncharted and though we do not see her much, we hear of her and there is a tragic note in her disappearance.

Perhaps that too, is her individual choice.

Swati leaves Manda and Pavani for Russia.

Swati leaves Manda and Pavani for Russia. Here in Russia for a brief period she finds love and peace with Misha only to lose him to a mechanical and exploitative system. The Babushkas (grandmothers) are a powerful image of an ageing nation. They have seen and suffered much and now eke out a cramped existence. Swati returns to India to take charge of the mute Pavani. She is an adolescent who has been raped and is the mother of a baby boy. The story ends gently but strongly.

Social Justice

In conversation about the title of the novel Sujata Sankranti says, “Because the so-called theories for social justice have now become legends foreshadowing us or giving us a shade for survival, we live in the Shadow of Legends either to take shelter in or to be forever shadowed by them.”

A lucid tale of two countries. The dedication reads, “For all those men, women and children who history owes recall.”

Photo sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Astute reviewing is a rare and special accomplishment. This review is one such. Thank you, Roopali, for this insight into a singular fictional composition.