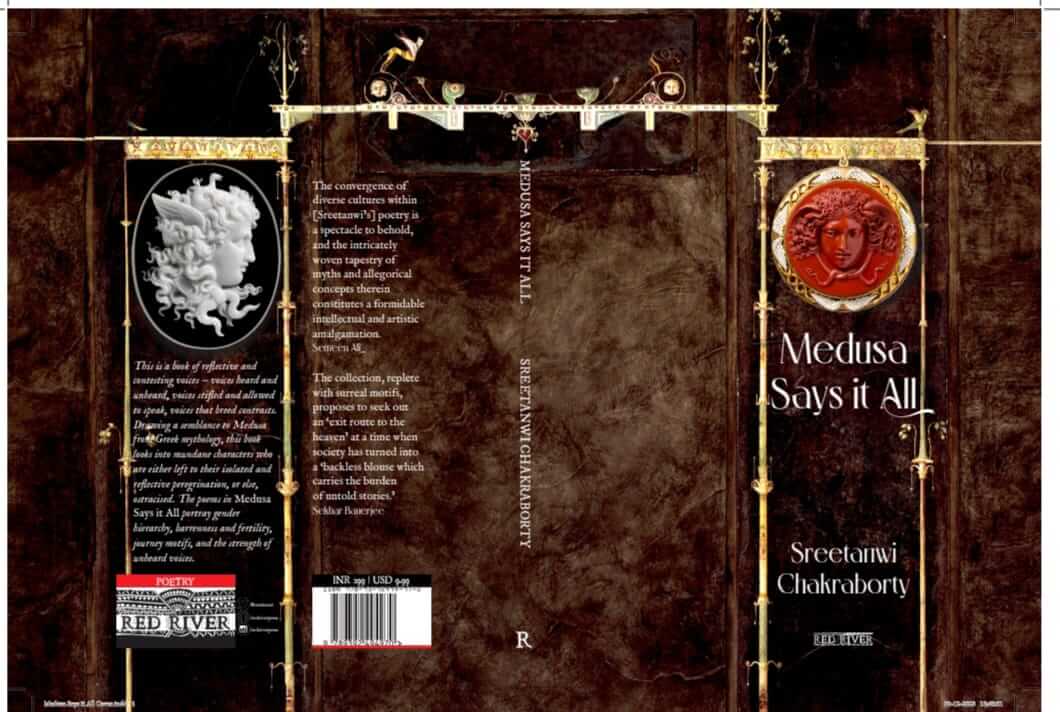

“Medusa Says it All” by Sreetanwi Chakrabarty explores themes of femininity, spirituality, and urban life, featuring vibrant imagery and diverse voices, reviews Dr Ajanta, exclusively for Different Truths.

Sreetanwi Chakrabarty’s latest collection of poems, Medusa Says it All (Red River, 2024), is a rich and intricate tapestry of motifs, weaving ancient myths and modern stories into a primordial pattern of significance. Divided into two sections, ‘The Woman on the Other Side of the River’ and ‘All My Life I Grew Up Wanting,’ the book comes into its own with the mentioned halves complement each other, and creating an overlapping oeuvre in which contexts converge and meanings merge through a mélange of metaphors.

Poet, novelist, reviewer, painter, academic and digital content creator, Sreetanwi wears several hats, her multidisciplinary orientation, helping her to evolve an aesthetics of generic and stylistic amalgamation.

The first section, in keeping with its title, is suffused with divine imagination.

The first section, in keeping with its title, is suffused with divine imagination. Beginning with an evocation of the feminine supernatural, the image of the “Yakshini,” it acquires various manifestations in the poems that follow, becoming in “The Accused,” a witch, an effigy, “the cursed white doll;” the “yogini” in “Shivalik and the Yogini,” who bewitched “many devotees to her shelter,” or alternatively, ” the “lady warrior / on the billboard” on “The Giant Wheel,” who is attributed with building the eponymous contraption facing the squalid cityscape, the wheel that is later identified with the “Pushya nakshatra” even as the “warrior lady/ scoops out belladonna pods,” no doubt, to ease the pain of existential suffering in cities of perpetual unease. From the image of woman as warrior, healer, and sensual siren we move to that of the nurturing mother in “Shivalik and the Yogini,” where she

becomes the primitive mother

with monsoon milk that nourished

an ancient Shivalik regime.

The yogini develops from the prurient to the parturitating female, whose fecund body, expansive like land or poetic text, sustains humanity with the monsoon of the skies and the imagination. In “The Transistor Radio,” she is “the radiant Goddess Durga,” emanating cosmic cadences of love and power.

She is, at the same time, the “madwoman selling/fate line on the laterite pathways” in “Amaltas and the Water Hyacinth,” even as in “Reflection on the Asylum,” incarcerated in a madhouse and constrained within “the last bend of the blind alley,” she may also be identified with Devi Sarpamasta, an indigenous version of Medusa. Myths tangle across epochs and traditions in the potpourri ofperfumes, that is Chakrabarty’s poetry. In “The Art Connoisseur,” the painting in question depicts the body of “a woman / a mother, a goddess, / a beloved under the vernal sky, / a secret paramour with a leopard tattoo / on her plump thighs,” teases viewers/readers with its ambiguity, challenging them to identity it as it blurs distinctions, not only between the mythical and the mortal but within the latter subset between the “mother” and the “paramour,” two polar opposites in popular perception. She is also the “belligerent woman” in ‘The Woman on the Other Side of the River’ whose dark brown eyes turned men into stone. At the chilling end of the poem

she gazed and gazed

but nobody was alive

to be turned into stone.

The second section, by contrast, has to do with the chaotic, contemporary scene, dwelling as it does on the cityscape, predominantly that of Kolkata but also considering the urban landscapes of Mumbai and Uttarakhand. It comes alive with a dozen frenzied tongues expressing its horror at the sordid and soul-killing transactions of modern, metropolitan life – “death, disillusionment/ and rat-eaten spinal cords,” along with “blood, phlegm and sweat,” (“Alternative”) and a home that is “mildewy, unventilated, and dismal.” (“The Tarot Reader”).

One of the strains that unites the two sections is the search for spiritual salvation.

One of the strains that unites the two sections is the search for spiritual salvation. The sublime and the surreal are resonantly captured in the mundane and the momentary. Siddhartha’s absence as he negotiates nirvana is emotionally located in the absence of the truant lover in the poem “Days When You Stopped Calling:”

You were the Buddha, Sujata's Amitabha,

bent on the path of transcendence,

you disappeared.

Such unlikely equivalences, through their balancing of distances between the mystical and the quotidian, serve to steady the throbbing rhythm of a poem in mesmerising motion.

Images of enlightenment tantalise the spirit with their elusive hints in both sections, suggesting an Elysium eagerly sought but rarely obtained.

Images of enlightenment tantalise the spirit with their elusive hints in both sections, suggesting an Elysium eagerly sought but rarely obtained. In the first section, these intimations cohere in “the tunes of the broken flute” that the snake charmer played in the poem “The Woman on the Other Side of the River,” the all-cleansing ‘Vaitarani River’ in “The Golden Minaret, and “the buds of Nirvana” in “The Retrograde Venus,” not to mention the world reposing in Nataraj’s eyes in “Inscriptions on the Brihadeshwara Temple,” to cite a few examples.

Instances of the same in the second section are, by no means, absent, appearing as they do in several poems, haunting the verses with their hints of a higher reality beyond the scope of ordinary human experienceexperience, but the real here largely replaces the mythical.m “Breathing Through the Veins of Eternity—Darjeeling,” for instance, the elemental union of river and sea symbolises the ultimate communion of man with his Creator:

… the Teesta flowed

into the vestiges of eternity,

in a timeless current, embracing...

whispering secrets of cyclical grace

and the sacred dance of life.

The last stanza of “Alternative” sums it up with a profound sagacity often overlooked for its beguiling simplicity of lilt and langue:

I'll seek sanctuary

in the farthest reaches

of the world,

after being drenched

in the downpour.

The image of the “broken asphalt arteries” heading to “heaven” in “Kaleidoscope” is similarly expressive of the fragmented and the fractured achieving fulfilment through the transcendence of its material limitations. The notion of the journey, scaled down in this section from its exalted aspirational momentum in the earlier one to the recognisable elements of a humdrum commute, is yet invested with symbolic overtones:

The commuters jostle across a steady passage,

on to the stairs of an illusory platform,

waiting for the carriage that will take them

to some unknown destination.

The divine saviour, too, is bathetically visualised as the “deliverer in the driving seat” in “Streetbuses.”

Interestingly, the ultimate reward for incessant spiritual striving is couched through striking paradoxes in both sections.

Interestingly, the ultimate reward for incessant spiritual striving is couched through striking paradoxes in both sections. It is the “myth laden city scavenger’s bag” in “Edifices of Shadows,” the “bowl of dumbfounded dreams” in “The Woman on the Other Side of the River,” and the love stories of Shyama and Junaid locked up in the weaverbird’s nest in “Amaltas and the Water Hyacinth.” The poignant, powerful, and plangent imagery in a poetic landscape awash with sensuous colours, shapes and textures create a swirling cornucopia of forms caught in a dynamic synergy.

Beneath the apparent diversity and diffusion, there is an underlying principle of unity which seeks to impart a focus to the collection. Love is one such strain that unites the two sections through its delirious dialects of desire and dream. Love as emotion, ideal, act, song, and dream – laces this cultural concoction with its inebriating essence. Rising from the earth, mingled with the seasons, and pulsating in the plasma of pain, it fills the veins of the present body of poetry with the precious ore of an ineffable intuition that transcends all previous experiences.

Whether it is the Yakshini “rubbing kewda attar into the/ cleavages of picketed time* in the first poem; “the raucous numbness of love” in “Love’s Scent in the Metropolis,” or the “droplets of love dripping / into the cashew nut navel of eternity” in “Harmony,” love, in this collection is a heightened expression of felt experience in its multitudinous manifestations. The speaker in “The Retrograde Venus,” for instance, finds “purgatory and the whole samsara” in the lover’s “chaotic charm,” stitching “cedarwood kisses” in her arteries.

Chakrabarty in Medusa Says it All is unabashedly the priestess of passion…

Chakrabarty in Medusa Says it All is unabashedly the priestess of passion – be it the frankly senuous exploration of romantic love, at once virginal and voluptuous, a tactile sensuality for poetry and its words and rhythms, or an iridescent infatuation with beauty in its various forms. Images come pouring out of her in a prodigal profusion of forms and finishes that tease the mind with its kaleidoscopic configurations.

Yet, within this lush euphoria of excess and extravagance, there is somewhere a quiet recognition of life’s low points that forces one to acknowledge the negatives of the human condition. The poem “The Voyagers,” expresses this organic awareness of the directionless modern man by comparing him to “a voyager / with a compass in his hands / and nowhere to go.” The poem “Marathon” organises the sense in a similar manner, visualising a time of day (morning) as a train: “As the morning gets ready / to jump on the fishplate of life.” In the poem “How are you, Afroz?” the image of the “tattered tarmac of a body” speaks of the weariness and passivity of the human, particularly the female body, which absorbs the shocks of innumerable touchdowns.

It is precisely between euphoria and epiphany that Chakrabarty’s poetry takes shape…

It is precisely between euphoria and epiphany that Chakrabarty’s poetry takes shape, as she says of a maturing vision in “A Road Trip to Manali,” it burgeons between” cacophony and carnival, / claustrophobia and carcasses, / clowns and chandeliers… creating a constant, undying litany.”

Cover photo sourced by the reviewer.

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By