Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca’s memoir, “Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father,” offers a profound exploration of her father’s life and legacy, blending personal reflections. A review by Urna, exclusively for Different Truths.

There are dazzling poems, and there are iconic poems. And then, there are the big daddies of iconic poems.

Poems belonging to the last category are known for smashing to smithereens the proverbial box, exploding the template, shattering the old paradigm, and altering one’s perception in such a way, that you somehow can’t revert to your old self, once you’ve read such a poem.

Yes, I am talking about none other than the iconic Night of the Scorpion by Nissim Ezekiel. Widely taught in schools across India, and an integral part of NCERT and ICSE English textbooks, the Night of the Scorpion not only introduced pyrotechnics of the poetic kind to my young, formative mind but forever changed how a young girl in class VIII viewed poetry. Along with some of my earliest understandings of what makes for a piercingly compelling poem that can look at a society, suffering, and superstitions, unflinchingly in the eye.

“The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled….”

John Berger writes in his seminal work, Ways of Seeing, “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sunset. We know that the earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight.” True to Berger’s words, my lifelong quest to understand the mind of the poet who wrote the Night of the Scorpion, my writer’s need to decode the phenomenon called Nissim Ezekiel, can only feel crumbly and half-baked without this earnest excavation into the stratospheres of Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca’s life, mind and memories, as we get to understand her “father” – the indulgent “Daddy” on the centennial of his birth.

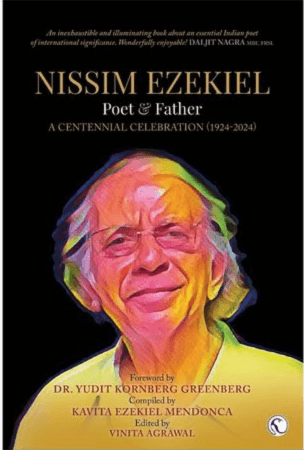

Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924 -2024), written and compiled by Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca, edited by the esteemed poet and editor, Vinita Agrawal, and published by Pippa Rann Books, UK, is everything and more than what one can expect from a work as staggering as this.

The book begins with a resplendent foreword by Dr. Yudit Kornberg Greenberg, the Founding Director of the Jewish Studies Program at Rollins College, Florida, USA, and a gorgeously perceptive introduction by Vinita Agrawal. Agrawal sensitively and succinctly sets the tone, “Memoirs often record the psychological pressures of growing-up years. This one does too. But it does so with amazing courage and fortitude, poignancy and frankness, honesty and originality, making it a particularly rich and rewarding read. Agrawal delicately draws our attention to how, “In intertwining her father’s story with her own, Kavita holds nothing back, leaving the reader marvelling at how much life exacts from mere mortals”.

A memoir always has at its heart, a mist-laden, nostalgia-smeared time travel…

This is indeed a deeply intimate and stirring memoir by the eldest daughter of the “Father of Post-Independence, Contemporary Indian English Poetry” wherein she gently holds our hands and takes us on a trip down a sepia-tinted cluster of memory lanes. A memoir always has at its heart, a mist-laden, nostalgia-smeared time travel, and Mendonca with her poet’s sensibilities takes us back to a time when Mumbai was good-old “Bombay” with samosas served with green chutney at Café Naaz. When soft, fluffy, piping hot naans with Rogan Josh at the Kwality restaurant were the stuff family outings were made of, and a doting Daddy always bought his eldest daughter, the apple of his eyes, orange and vanilla stick ice cream.

An intoxicating tale, Mendonca’s memoir is a reflective meditation on both the ubiquitous appeal and the complexity of Nissim Ezekiel as a poet, public figure, critic, editor, mentor, friend, and family man. But to his eldest daughter, Kavita, he was above all else, the loving father who prophetically gave her the name “Kavita” – a name that would bear within its embryo the trajectory of her lifelong journey of poetry.

“Kavita” which means “poetry” then is not just a name but a revelatory map upholding a poetic destiny, that would unfold across the continuum of time, space, and continents. A sacred covenant planted within the soil of Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca’s identity, that would blossom and ripen as she traversed a long, arduous road from Bombay to Mussoorie to Calgary, Canada.

Mendonca… brings an unfettered kind of courage and refreshing candour to her memoir and opens the throbbing seams of some of her deepest vulnerabilities.

Mendonca, in my opinion, brings an unfettered kind of courage and refreshing candour to her memoir and opens the throbbing seams of some of her deepest vulnerabilities, as she eloquently describes the long wait for her father at her window, on evenings that stretched into expanses of the territory of the blurry uncountable, the fuzzy immeasurable.

“He took the train from Bombay Central Station, a fifteen-minute walk from his home to Churchgate each morning, and was at his desk at promptly nine a.m. After his cataract surgery and even in the throes of Alzheimer’s, he insisted that he wanted to go to the PEN office. “I’m needed there,” he would say. I wonder if he knew how much he was needed ‘here,’ where I waited patiently for him, in what seemed like a lifetime”.

~ Page 29, Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924 -2024)

This idea of the long and restless wait morphs into a poem embodying the slow burn of ache, that can only be written by a daughter who knows that marking time often comes freighted with meaning, especially when a child has to live away from her mother and other two siblings, given the cruel hand that fate hands out, at times.

“Waiting for Daddy

Daddy, the poets have gone home now

They have taken their commas and full stops with them

You must be hungry now, daddy

Let’s have lunch together,

I have brought along my poem

But it can wait,

I can wait…”

~Page 178, Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924 -2024)

Throughout her memoir, Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca doesn’t shy away from addressing the elephant in the room – how does one go about undertaking the mammoth task of writing about a father who is such a larger-than-life personality? “Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca treads this complex ground with wisdom and sophistication as she creates a commemorative volume for Nissim Ezekiel…blending her personal narrative with the public fame of her father” observes Professor Malashri Lal, distinguished poet and Convenor, English Advisory Board, Sahitya Academy.

Mendonca swims through the ebb and flow of this personal tsunami of intense currents, armed with an emotional quotient that is a rare skill as she brings to light revelatory glimpses buried in the isolated crypts of her memory. Adroitly piecing together bits and pieces, sharp edges and jagged corners, resurrected songs and the chiaroscuro of a symphony hall – as the reader soaks in the tunes of the orchestra of Mendonca’s life, her father’s life, and the intermeshed lives of all the people she loves with every grain of herself. Sukrita Paul Kumar, eminent poet and Guest Editor of the Sahitya Academy Official Journal, Indian Literature, talks about Mendonca’s “restraint and the matter-of-fact style” creating “a heartwarming intensity”.

… Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca feels the pulse of pain, her re-visitation of many a childhood hurt acquires the sensibility of art…

What struck me as I got immersed in the pages of the memoir, is that even as Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca feels the pulse of pain, her re-visitation of many a childhood hurt acquires the sensibility of art – transforming the ache into an uplifting magic carpet flight of remembrance, a longing for the way things were once upon a time, a softened understanding, and forgiveness.

“When difficult memories surface, I simply want to turn back time. Knowing the impossibility of doing so, I turn to prayer. Every family has its tragedies, none are spared. Many have suffered greater tragedies than mine, though at the time it was not easy to look at my suffering in that way. Now, I often find comfort in the words of my father’s poem ‘Acceptance’:

I am alone

And you are alone.

So why can’t we be alone together?’

In a broader sense, my father and I were alone together”.

~ Page 47 and page 48, Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924 -2024)

Sensationalism is a much-discussed and examined topic when it comes to memoir writing, and one only holds Mendonca in higher regard than one already does, at the way she takes the bull by its horns. We all, at some level, understand, how any narrative can often be littered with sensationalism, wherein truths are inflated to seem more hyperbolic and dramatic, and fact-telling becomes reductionist in nature, stooping to a cheapened modicum of grabbing more eyeballs and baseless gossip, aimed solely to generate higher ratings, never mind at what cost.

Hence, when Mendonca takes instances of incorrect fact-telling and sets them straight, one is almost rewarded with a sense of firm finality – a semblance of poetic justice. For who else can set the record straight other than the eldest daughter of Nissim Ezekiel, having worn the heavy cloak of the unwarranted and invasive intrusion of populist distasteful speculation and mudslinging, robbing a public persona of his right to personal space and his loved ones that of personal human dignity.

“Every family has its traumas and, for us, my father being a public figure, meant our personal space and his, must remain out of bounds. Or, it descends to the level of speculation

and gossip. The truth is only known to those intimately involved. My father made no mention to anyone, of how or why I was sent to live with him as a young girl. Those who knew it were relatives, close friends and neighbours.”

~ Page 39, Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924 -2024)

Mendonca’s memoir has fluffed out into a much larger, layered, and all-encompassing in its dynamicity and wingspan…

In my opinion, Mendonca’s memoir has fluffed out into a much larger, layered, and all-encompassing in its dynamicity and wingspan, than the memoir she set out to write initially. For as we climb up the dainty steps of this carriage of “time-travel” of Mendonca’s journey, seated along with her, witnessing her life through her mind’s eye, one image pixelating into another, like as in the movies playing in Bombay’s Regal Cinema, one cannot overlook the love and sheer grace with which Mendonca acknowledges the role of the entire extended family, in making her who she is today.

“At the Retreat I was raised by the proverbial village. Extended family, cousins, friends, and neighbours filled my lonely hours with the fun and love a child craves.”

~ Page 59, Nissim Ezekiel, Poet & Father: A Centennial Celebration (1924 -2024)

She acknowledges, validates, and doffs her hat poetically to everyone inhabiting the spectrum of her life. Her memoir is a re-telling of everyday complex human events and kind gestures tinged with an immersive visual urgency and also doubles up as a map of extended family dynamics and the cruciality of uncles, aunts, and cousins in glueing the cement of one’s childhood.

She talks about her grandmother’s home, ‘The Retreat’ – built in the days of the British in 1894 and how different it was from Breach Candy, with its large garden outside the ground floor rented flat. The starkness of the imagery reiterates a young girl’s longing and perception of “home”, and yet Mendonca stretches the yarn of grace further and further as she acknowledges every uncle, every aunt, every cousin, every friend who comprised a thread or more in the stitching of the all-too-human, the all-too-tender fabric of her childhood.

Perhaps, this sense of community that we find ourselves happily partaking in almost leap-frogs into the qualitative pulse of the book as the gears shift from Mendonca’s intensely personal memoir to a collective memory holder, the keeper of all that is sacred and sacrosanct for the poetry collective as a whole, as the book also includes essays and notes from fellow-poets, mentees, friends, students and family.

Adil Jussawalla, iconic poet and critic remembers Nissim Ezekiel fondly as he writes, “My leftist assertions didn’t suit Nissim…”

Adil Jussawalla, iconic poet and critic remembers Nissim Ezekiel fondly as he writes, “My leftist assertions didn’t suit Nissim, and they sometimes got in the way of our friendship. But that friendship never broke. He was warm, understanding, and precise in his manner and speech until Alzheimer’s struck him. I owe him a lot and continue to think of him as an indispensable friend and guide”.

Alan Mendonca, Nissim Ezekiel’s son-in-law, married to Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca shares some heart-warming nuggets that convey so much about the man behind the larger-than-life persona called Nissim Ezekiel, in Verses from a Poet’s Life. Alan Mendonca writes, “Kavita and I spent a sabbatical at Oxford in the early nineties. During that year, Nissim was invited to read his poems in England. He decided to first stop off at Oxford to spend a few days with us. I wrote him precise instructions on the bus service from Heathrow to Oxford. At the appointed time, I set out for the bus station on my bicycle with my daughter to receive him. After waiting for two hours, I decided to head back home, since Nissim had not turned up. There he was, in our living room, having a cup of tea with Kavita. When I asked him how he got to our place, he told me that a lady on the plane had offered to give him a ride to Oxford (she would be passing through) and drop him off at our home. She said she had met him on one of his poetry reading sessions on a boat ride on the Thames ten years earlier. ‘Wow!!’ we said admiringly. ‘Who was she? What’s her name’? Nissim replied, ‘I don’t know; I can’t recall meeting her’”.

Elkana Ezekiel, Nissim Ezekiel’s son and the youngest of the three children, gives us a glimpse into the birthing of poems, in his piece, For Me He was Just ‘Dad’, “In our home, we learned to recognise the signs when Dad was writing something new. He would grow silent and engage in several tell-tale activities. Some pranayama, loud enough to frighten away the neighbourhood stray dogs, a few lines, a walk in the garden, a few lines, lying down with a crumpled hanky across his eyes, a few lines. Till finally it was done”.

Fiona Fernandez, revered journalist and author writes… about the importance of legacy, “Kavita is keen to keep his legacy alive….”

Fiona Fernandez, revered journalist and author writes in her eloquent piece, about the importance of legacy, “Kavita is keen to keep his legacy alive. She discusses his poetry with today’s younger generations of poets, who might not be acquainted with it.” Fernandez too traces the process and technique of writing a poem, as observed and chronicled by Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca in her poem, How Daddy Wrote His Poetry.

Gayatri Mazumdar, eminent poet, writer, and publisher, remembers with equal parts, fondness and admiration, “In retrospect, I recognise what a large-hearted magnanimous person he was! He made each one of us feel special and important and treated us all equally. Apart from this, he also made himself available to every visitor who dropped by at Theosophy Hall. Nissim could be extremely involved yet detached, persuasive yet tender in a strange sort of way. His door was always open for whoever came in. He also had this delectable sense of humour.”

Gieve Patel, venerable poet, playwright, and painter recounts with affection about Nissim Ezekiel’s interest in education per se. Patel writes, “It is quite possible that this was derived from his closeness to his mother, who was a school principal, and who had a life-long association herself with school education. Nissim showed a great deal of interest in primary and high school education. I have a memory of him, after he returned from a trip to Goa, asking me to visit a school there. His eyes shone as he said: ‘This is grassroots education, the school has evolved from the very soil around’.”

Jeet Thayil, renowned poet, novelist, and editor writes in his unputdownable piece, 14 Attempts at a Tribute, “In time he would come to define Bombay as much as the city would define him. It is a looming presence in his poems, a kind of purgatory, or a far circle of hell. He wrote about it without resorting to easy sentimentality, and he sometimes evoked the tormented images of Baudelaire and Dante. From ‘A Morning Walk’:

Barbaric city sick with slums,

Deprived of seasons, blessed with rains,

Its hawkers, beggars, iron-lunged,

Processions led by frantic drums,

A million purgatorial lanes,

and child-like masses, many-tongued

whose wages are in words and crumbs.”

Kamal Balsara-Bacha, who was a student in … Mendonca’s class at Woodstock International School, talks about “serendipity.”

Kamal Balsara-Bacha, who was a student in Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca’s class at Woodstock International School, talks about “serendipity.” Balsara-Bacha says, “Serendipity. It’s a word I first learned in Mrs. M’s AP English class. Since then, it has come to define many aspects of my life and the intricate way life threads its way back, almost like a honing device…” And then, “some years later as a teacher I had the honour and privilege of teaching his ‘Night of the Scorpion’ to my 10th-grade class. I began the session by telling them I had to be the luckiest person there. I had not only had the privilege of meeting and interacting with him but had in large part become a teacher because of his daughter who I was serendipitously now back in touch with.”

Menka Shivdasani, esteemed poet, editor, and journalist articulates the essentiality of craft and gives us a close peek into Nissim – the mentor. In Shivdasani’s words, “As I got to know him better, I realised that this was someone who truly cared about nurturing good poetry, who was generous with his time and advice when he thought someone had potential. I think people sometimes take this for granted. I remember a teenage boy once walking into the PEN office and demanding to know if Nissim had read his manuscript. Nissim sheepishly mumbled that he hadn’t been able to do so, only to be angrily told – “But you’ve had it for a month!” Instead of throwing him out, Nissim apologized and promised to look at it as soon as possible.”

Mohana Rao, who was also a student of Mendonca at the Woodstock International School, beautifully writes about the stars lighting up the Himalayan skies, “Setting the stage for a lone poet fighting his fatigue to compose his immortal verse, concluding his poem by juxtaposing two shining teenage stars against the greying man on the moon. The man who today through his lyrical artistry is the glistening star, he once scribed late into the night under the shimmering midnight sky.”

Olinda Belt, another student of Mendonca at the Woodstock International School tells us about her cherished possession – the poem called Lost and Found in Mussoorie. Belt writes, “I have carried this treasured, handwritten piece of poetry to twelve different cities, three different continents and numerous different homes. This was an effortlessly written piece of poetry by Mr Ezekiel, but for me a little bit of the past captured and preserved.”

Rose says, “I felt that Nissim was a kind man. I could see that in his face. But I also knew that he was a demanding artist….”

Raul da Gama Rose, a well-known poet, and music critic, talks about Nissim, the man, and Nissim, the artist. Rose says, “I felt that Nissim was a kind man. I could see that in his face. But I also knew that he was a demanding artist. After all, he didn’t get there by dashing off the first things that came to his mind. At a subsequent meeting, he told me, ‘The gift of writing makes you an artist, but you have to develop the attitude of a craftsman. And you can only do that if you work at the gift… chip away at the extra bits, trim the rough edges… chisel away at the words…’”.

Saleem Peeradina, a distinguished poet, writer, and editor takes the reader through a little story about Ezekiel’s spectacles, which he had been wearing for 25 years. Peeradina writes in detail about how the spectacles “tilted precariously on the bridge of his Jewish nose, their glass surface smudged and scratched, their rivets caked with the rust of a quarter-century. This was the pair that Ebrahim Alkazi, an old friend and Ezekiel’s contemporary in the theatre, had found for him, escorting him to the oculist”.

Salil Tripathi, esteemed journalist, editor, and author talks about having lunch with Nissim. Tripathi shares delectable tidbits, as he narrates how “Nissim used to eat lunch every day at Sanman, a restaurant next to the American Center, the American library, in Bombay. I knew him as a college student (I studied at Sydenham, which was nearby). And during those long summer months…some of us would go to Sanman for lunch. I would meet Nissim often then – he had read my early poems, and we often talked about literature. If my staple diet was idli-sambar, his was boiled vegetables with mayonnaise.”

Shalva Weil, renowned author and Senior Researcher throws light on Nissim’s evolving mindscape in the context of the Bombay cultural milieu. In Weil’s words, “Of course, Nissim wasn’t only a poet. I followed his development avidly. He was a playwright, a reviewer and more. Since my major interest was Nissim as a Bene Israel, my favourite poem was and is ‘Jewish Wedding in Bombay’ with references to Jewish law and custom, as well as real insights into ceremonies and what we call “love”. However, today I realise one has to view Nissim in a wider perspective against the backdrop of the evolving Bombay cultural scene”.

Shanta Acharya, respected poet, and novelist writes about how, as a young poet, “publication in the Indian P.E.N. seemed like a miracle of sorts as I had sent my poems without any hope of an acknowledgement, let alone publication. Taking into account the erratic postal service and mysteries of the publishing world, I had no great expectations. Imagine my surprise when a reply arrived within a week! Signed by Nissim Ezekiel, it said my poem ‘Caligula’ would appear in the forthcoming issue… That is how I ‘met’ Nissim Ezekiel”.

Subodh Deshpande… writes an achingly beautiful poem about the loss of a mentor, in his poem I Lost My Nissim Ezekiel.

Subodh Deshpande, a reputed poet and brand consultant by profession, writes an achingly beautiful poem about the loss of a mentor, in his poem I Lost My Nissim Ezekiel.

“I lost my Nissim Ezekiel in

a hotel lobby in Istanbul

I was on the edge of discovery

That bit where he talks about

writing good poetry

My enlightenment deficient

My halo incomplete

like a half-eaten donut

I feel like:

…my mentor turned his back on me

…I gave up tennis just as I was

mastering my backhand...”

Sudeep Sen, an eminent poet and editor writes an evocative Haiku Triptych for Nissim Ezekiel.

“Handwriting

linked-haiku tercets

fingers hold the pen

firmly, guiding the gold nib

in wild cursive scripts —

lines delicately

etched, perfectly pitched with the

stylised slant of a

fine and practised hand —

letterforms and words

bloom, come alive — spell”.

Sujatha Mathai, the deeply revered poet writes about Nissim, wearing the editorial hat. Mathai shares how “Once he gave me a lovely bit of editorial wisdom. I had a line –“held together by sacred bonds”. He suggested I change the word “sacred” to “secret”. I immediately accepted it as “just right.” It was the most innately apt editorial advice I ever received”.

The book fittingly ends with detailed, in-depth interviews for the deeply invested reader. When renowned poet and reviewer Jaydeep Sarangi and prominent poet and academic Basudhara Roy ask, “A large number of critics opine that modern Indian English

poetry started with your father. What do you think about it?” Mendonca summarises and puts things into perspective especially the legacy of Indian English Poetry. Mendonca writes, “This has been a widely acknowledged fact, and I am humbled and proud to be the daughter of a man who dedicated his life to poetry, and to tirelessly mentoring so many younger poets and writers.” Yogesh Patel, MBE, award-winning and widely recognised poet, and author also brings up this point – the overwhelming weight of the “legendary legacy to Indian English Literature”, as Nissim Ezekiel certainly was a foundational figure and has been called “The Father of Modern Indian Poetry in English”.

Usha Kishore, renowned poet, and editor, in her interview, digs deep into the question of the Indian Jewish identity…

Usha Kishore, renowned poet, and editor, in her interview, digs deep into the question of the Indian Jewish identity and how it “cannot be considered in a Western context”. And Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca talks about how Nissim’s poetry was “no ‘dialogic response’ to any faith”. And instead, how “the writing of poetry was central to his life”. And it is this quality of Nissim Ezekiel – his unquestioned lifelong dedication and devotion to poetry, that continues to fuel the unextinguishable hearth-fire, inspiring generation after generation of poets writing in Indian English, across India and the diaspora. Amritjit Singh, Langston Hughes Professor,

Ohio University states, “More than ever before, we can identify today with Ezekiel’s India instead of Naipaul’s and appreciate the “backward place” he chose to be part of”.

In conclusion, the word “memoir” carries with it the unuttered burden of the narrative being underpinned by the intersectional intensity of the personal and the autobiographical. Yet Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca upholds through her memoir’s sensitised rendition, of what can only be described as the Light of the Sabbath. Replacing being with interbeing, as Thich Nhat Hanh would say, distilling to the reader gleaming rubies and sapphires of discernment…having been there, seen that, done that.

Truth be told, the spectacular, the sacred, the poetic, and the magical cannot be captured in mere words, but at best through a liminal kind of world-building. And, this is the kind of immersive cosmos that Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca assiduously stitches into a singular variegated assemblage with her trademark fluidity and the poise of her attentive being.

At the epicentre of this cosmos, we stumble upon, as we read her memoir, a certain kind of Holy Trinity – that of Release, Resolution, and Redemption. And thereby, what starts as a personal memoir billows out into the full-bodied, golden harvest of a collective memoir, where friends, family, fellow poets, students, mentees, and obsessive fans of Nissim Ezekiel congregate at a sun-lit bower. Bringing to this bower, souvenirs and keepsakes from their own personal memory boxes, to bring alive, laugh, cry, sing, celebrate, join hands, and raise a fitting birth-centennial toast to Nissim Ezekiel.

Feature image designed by Anumita Roy and cover photo sourced by the reviewer.

By

By

By

By