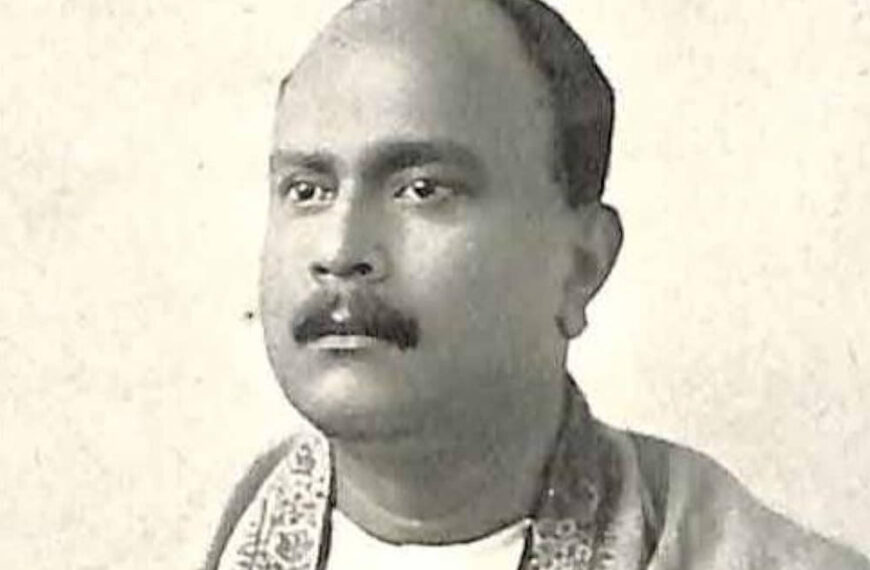

In the third and final part, the author, Azam, tells us that he borrowed two volumes of Khushwant Singh’s History of the Sikhs and Maharajah Ranjit Singh from Sadaqat, a classmate who had a close bond with him – an exclusive for Different Truths.

I borrowed both volumes of Khushwant Singh’s History of the Sikhs and his biography of Maharajah Ranjit Singh. I did an all-nighter with the first history volume, getting told off at the breakfast table for self-inflicted bleary-eyedness, and in Professor Tariq Jilani’s history class for dozing off! In the break, though, he had a big, indulgent smile when I told him why.

I had been delighted to discover — the delight of a work in progress, not the discovery — Khushwant Singh expressing in such seductively clear and scholarly prose what many Punjabis thought.

That the Sikh Khalsa spearheaded a Jatt-led agrarian revolution that threw off the upper-class yoke …

That the Sikh Khalsa spearheaded a Jatt-led agrarian revolution that threw off the upper-class yoke, then turned around to fight Afghans who had raided and levied tribute for a long time like it was their birthright! And the rest, as they say, is history, from the Khalsa triumph at the 1757 Battle of Amritsar to the 1813 Battle of Attock and beyond. After finishing the second volume and the biography of Maharajah Ranjit Singh, I coveted them. I wanted to have them, manipulated some money from my father, roamed all over Lahore, but came back empty-handed.

Despondent.

And then, fate dealt another hand.

Like a thunderbolt, the pea ‘twixt my ears exploded with the name — Sadaqat!

Of course, Sadaqat.

He’d said so.

“When you get married, Gill Badshah, the cardamoms and p’harjai’s Banarasi sari will be on me!”

I had taken it lightheartedly, but his eyes hadn’t been joking. And on and off, he would offer “koi khidmat, Gill Badshah (any service).”

And here’s the how and why of the recurring offer.

Sadaqat was a Gujjar classmate at FC College whose family ran Lahore Cantonment Sadar Bazar’s best and classiest falooda, lassi, milk, yoghurt, and kheer shop. He was the first in his family to go to college, and that, too, FC, which was difficult to get into, but he had obtained the necessary grade by sheer hard work.

He was probably the only one who pridefully wore the FC blazer every day from autumn to spring, complete with badge, college tie, pocket square and a Cheshire cat smile, rolling his shoulders, hands curled and ready for a grapple. He was a pehelwan wrestler built like one, so no one went beyond smirks or what they thought was a jibe he couldn’t catch. They were wrong, but the only thing was that he couldn’t afford to get into trouble. I was the only one who knew he was on bail for three counts of attempted murder and grievous bodily harm — section 307 Pakistan Penal Code.

On a cool autumn evening, I went to Gulberg main market for a stroll, to meet friends and for a lucky — perhaps — eye-up.

I spotted Sadaqat hemmed in by three superbly muscled attackers, one with a knife and the other with an axe handle.

I spotted Sadaqat hemmed in by three superbly muscled attackers, one with a knife and the other with an axe handle. I didn’t hesitate; we won the fight and found ourselves richer by a knife and an axe handle. The attackers had been pros — rival smugglers settling a score.

Later, there was a negotiated settlement, and they came specially to apologise to me, since I was a ‘civilian,’ complimenting me on my fighting skill, promising there would be no repercussions, and cheekily offering me part-time work, which, of course, I politely declined!

These smugglers called themselves border blackyas or commission agents. They brought gold and watches into India and brought cardamoms and Banarasi saris back. Nothing else — they were upper-crust blackyas and had their pride, principles, and prestige.

This was, of course, still 1968, about the time Mario Puzo was finishing The Godfather, and principled Corleone types thrived in many other cultures.

So, on occasion, I would go to Sadaqat’s family milk shop in Cantonment Sadar Bazar, and this time, as always, I relished the royal treatment.

Sadaqat’s older brother, whom we all respectfully called ‘P’haa jee,’ treated me to all the delicacies and then asked me if I needed anything.

He was shrewd.

I hesitatingly made my request.

There was silence, and then P’haa jee and Sadaqat burst out laughing. Yet, P’ha jee was impressed. “My younger brother,” he said about me. “Look at him. No cardamoms, no sari-shari, no Indian whisky, no ayashi, just two books. In angrezi. Written by a Sikh! Dasso!”

Two weeks later … Sadaqat shyly held out both hard-bound volumes in dust jackets.

Two weeks later, in college, Sadaqat shyly held out both hard-bound volumes in dust jackets. I punched him lightly and ordered tea, sliced bread, butter and shami kebabs. He was chuffed.

One-mum told me to slide them behind the other books — we were Christian, and bad-dad was a civil service officer, so we had to be careful since the author was a Sikh.

But there’s more, as life is prone to take sovereign decisions.

I passed all my Inter Services Selection Board (ISSB) tests to be admitted to the Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) Kakul and eventually, if successful, become a commissioned army officer. I was busy getting clothes tailored, bedding organised (you had to take your own in a canvas bistarband bedroll), and other things. Amid this bustle, a friend who knew I was the proud possessor of both volumes of A History of the Sikhs asked to borrow them.

After receiving my commission, when I went to his house to say hello and recover my prized possessions, his mum told me he’d left for the States to become a croupier in Las Vegas! A kind lady served me tea and peak freens lemon sandwich biscuits while she searched his room but could not find my books. Typically, he must have passed them on to somebody.

Thanking her, I left dejectedly, wondering why fate had dealt me such a cruel hand…

Thanking her, I left dejectedly, wondering why fate had dealt me such a cruel hand, but was rescued by Wasim Afzal, who offered me a double vodka at Faletti’s bar. I shrugged off my loss to destiny, drowned my sorrows in the Russian tipple, and that was the end of it.

Or so I thought, but fate wasn’t done with me.

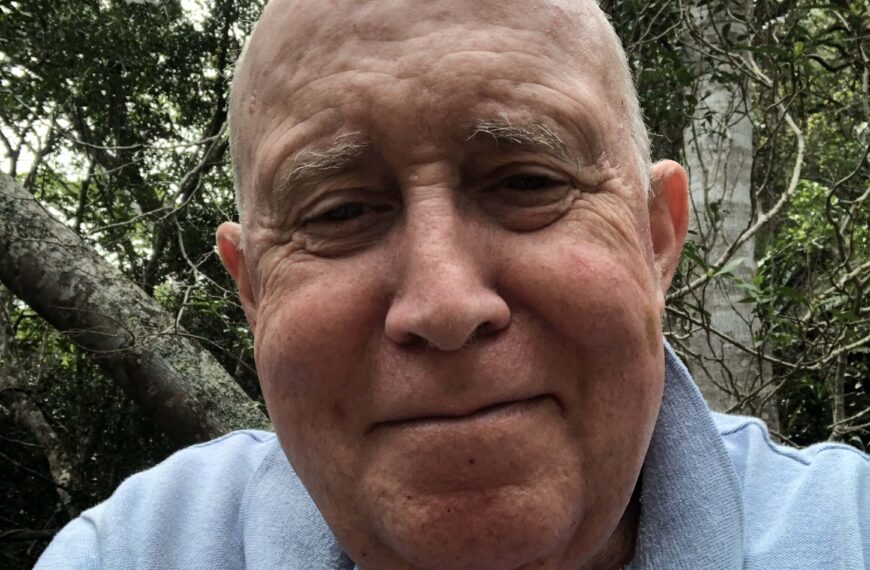

The army divorced me via a field general court martial (FGCM) for assaulting my CO on a matter of my troops’ honour. I served my prison sentence in Kote Lakhpat Jail, obtained my MA in English Literature with distinction, worked at the British Council Library, started writing, and did a short stint in the Middle East! Sanjay Suri, my charming and cultured neighbour, was a former Sub Divisional Officer (SDO) from New Delhi.

We often talked books, and he was delighted to hear me wax eloquent on the writings of Khushwant Singh …

We often talked books, and he was delighted to hear me wax eloquent on the writings of Khushwant Singh, especially Train to Pakistan and the A History of the Sikhs, which is also a history of Punjab. He felt my loss and promised to send me replacement copies of A History of the Sikhs. I reminded him not to post them from India! On this promise, I returned to Pakistan and got caught up in other things, and Sanjay Suri’s promise receded, then faded, though not his friendship.

Due to my authorship of Army Reforms and Jail Reforms, I had to leave Pakistan in a bit of a hurry, entered France on an asylum visa and joined the French Foreign Legion as a self-demoted private, bewildered by the language but not by the profession of arms in which I had training and experience way beyond what was required of a private.

Three months into the Légion’s training depot, I got a letter from one-mum (still in Pakistan) informing me that they had received hard-bound copies of A History of the Sikhs from a Mr Suri in the Middle East, and she wondered what was going on!

Engineer Sanjay Suri had kept his word, my family got the books, and thank you, Suri p’hai, wherever you are: respect!

And there’s still more.

When the rest of my family was leaving Pakistan, A History of the Sikhs joined Padree Thakurdas’ sitar…

When the rest of my family was leaving Pakistan, A History of the Sikhs joined Padree Thakurdas’ sitar and dadee-jee Surinder Kaur’s spinning wheel, charkha. Padree Thakurdas was one of Pakistan’s top sitarists, and Bad-dad, his apprentice, who had inherited the sitar which my Apa-jee, Ustad Ghulam Bheek’s student, played with bhaijan on the tabla, who was Ustad Qadir Bakhsh’s student. The sitar had occupied an honoured place in our living room, next to my grandmother Surinder Kaur’s charkha. They had to be abandoned to their ancestral soil, which one-mum, bhaijan and apa finally renounced.

So, the sanctity of a Hindu’s bachan might have seemed a fitting end to this erratic story, but then there’s the matter of this little addendum.

A configuration of favourable circumstances put me in a position where I found myself the first French Foreign Legionnaire let loose at a university to do a PhD. That happened summa cum laude, then I finished my Légion contract and finally started reconstructing my life which the court martial had deconstructed. I started teaching, getting published, falling madly in love, married, had children, and bought a house where books began appearing in trickles. Then, finally, I was able to, once again, reunite with trusted friends like Khushwant Singh, James Jones, Hemingway, Faulkner, Gerald Seymour, Manohar Malgonkar, and the rest of the gang. I am finally in a substantial, unobtrusive, available and sagacious company.

Concluded

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Fascinating

Thank you!