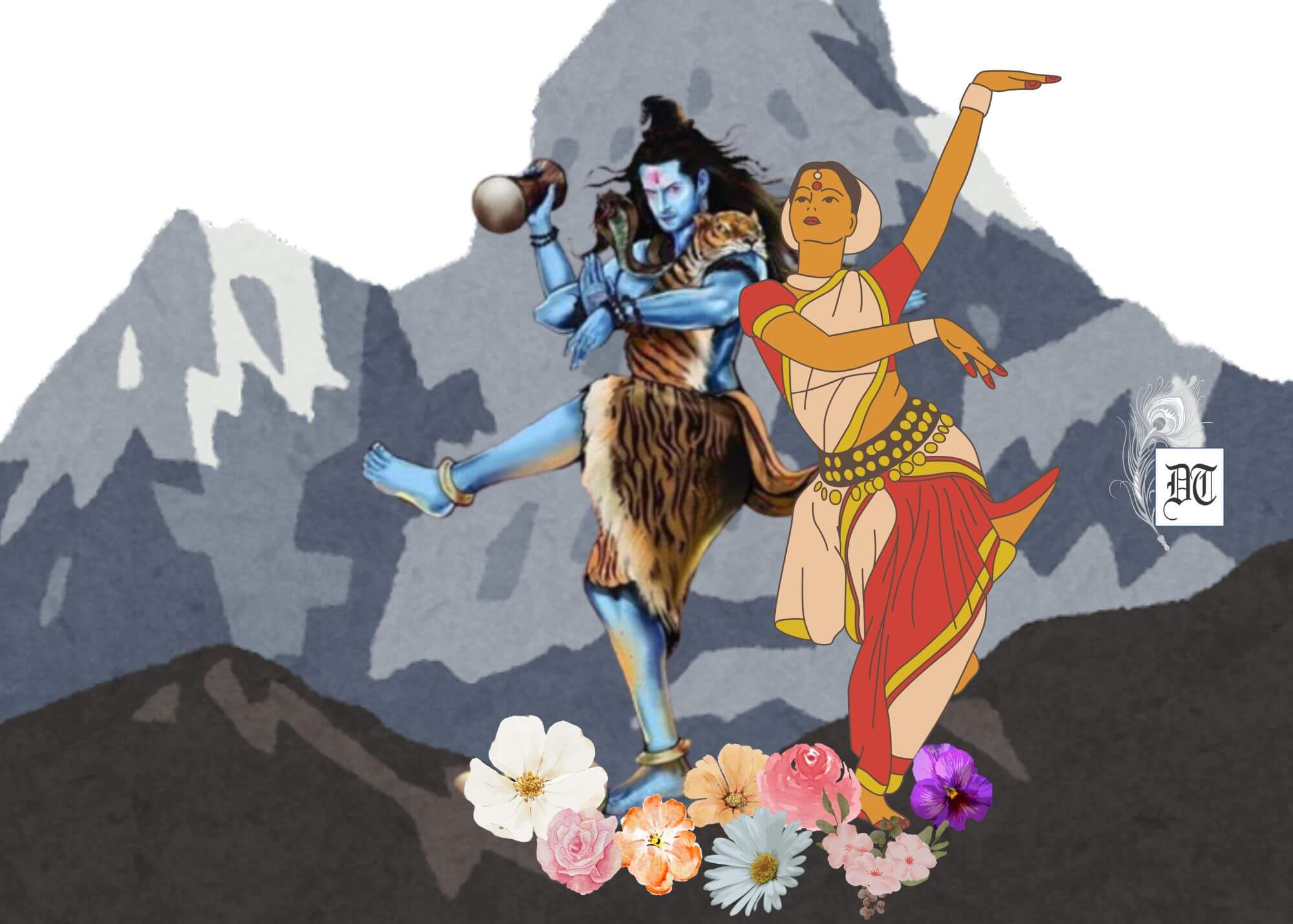

Sohini and Rishi explore Lord Shiva’s connection to Hindu mythology, the origins of music and dance, and the universe’s creation, exclusively for Different Truths.

Lord Shiva, who transcends the constraints of time and space, is the originator of all forms of artistic expression, including dance and music. The damaru (small handheld drum), resembling two triangles, served as the primal instrument that generated the sound responsible for the creation of the entire universe. The two components consist of the male and female, representing the concepts of yin and yang. The symbolic creation of the world commences when the lingam and yoni converge at the halfway of the damaru, and the destruction occurs when they disengage from one another. This contributes to the hypothesis of the Big Bang theory, which explains the origin of the universe as we currently understand it.

Shankarabharanam, which translates to ‘the ornament of Shiva’, is regarded as a therapeutic raga in the field of music therapy. The song is highly esteemed by Lord Shiva, who is revered as the Vaidishwar or deity of physicians. It is believed to evoke a sense of empowerment and overall wellness in those who listen to it. The five primary ragas in classical music, namely Shree, Deepak, Hindol, Megh, and Bhairavi, are thought to have originated organically from the ‘Panchmukhas’ of Lord Shiva.

According to Hinduism, music has its origins in Shiva’s five mouths. Shiva is responsible for the genesis of Saptaswaras (seven fundamental sounds) and musical instruments. According to legend, Goddess Parvati desired to learn about the origin of the Saptaswaras. Shiva divulged the concealed knowledge regarding the genesis of the swaras and musical instruments.

Origin of Music

Music’s origin is linked to Panchanana Shiva, often known as Shiva with five faces. The five manifestations of Shiva are Sadyojat, Vamdev, Aghora, Tatpurush, and Ishana.

The Gandharaswara emerged from Shiva’s countenance, as spoken by Sadyojat. There is a belief that the Earth also originated from this surface. The Mridangam, a musical instrument made from tree bark or animal skin, originated from the Sadyojat form. The Rishaba and Shadjam Swaras emerged from the Aghora face. Agni manifested from this countenance. Musical instruments featuring strings emerged from Agni.

Daivata Swara emerged from the countenance of Vamadeva. Water is thought to have originated from this source. Musical instruments such as the Shankh originated from Vamadeva Shiva.

The Panchama Swara originated from the Tatpurusha aspect of Shiva’s countenance. Air and wind emanated from the countenance of Shiva. Wind instruments, such as the flute, originated from Tatpurusha.

The Swaras Nishadam and Madhyamam originated from the Ishana aspect of Shiva. Space sprung from the countenance of Shiva. Musical instruments such as the Veena originated from Ishana.

Saints Disseminated Music

According to popular belief, the Saints, who acquired musical knowledge from Shiva disseminated it among human beings on earth. Raga Malkaus is a sombre and introspective musical mode. Its mood is sorrowful yet consistently steady as if achieving a sense of closure while reflecting on a significant loss. The raga possesses a straightforward five-note scale that is unique and unmatched by any other.

According to Hindu lore, the raga was specifically created to calm the anger of Lord Shiva, the deity associated with devastation. Sati, a princess by birth, chose to abandon worldly possessions as a tribute to Shiva, whom she eventually wed. The King, unhappy with this, insulted her and criticised Shiva’s character. Sati ultimately succumbed to her rage and transformed into the divine deity Adi Parashakti. The storms erupted, causing her mortal form to ignite, unable to withstand the immense force of the goddess.

Shiva was deeply saddened at receiving the news of his wife’s demise. He became extremely angry, hoisting the burned body of Sati on his shoulders and forcefully throwing two strands of his hair to the ground. The two Manibhadras emerged suddenly, manifesting as powerful warrior spirits with several arms. They brandished swords, tridents, and cleavers as they embarked on a relentless pursuit of revenge. Shiva became engulfed in an eternal Tandav, the dance of annihilation, while the band travelled around the world, beheading the king and massacring his retinue.

Sati and Parvati

The intense anger of Shiva caused much disturbance among the other gods, leading them to beseech Lord Vishnu, the deity responsible for preservation, for assistance. Vishnu reincarnated Sati’s spirit as Parvati, the deity associated with devotion and brought her back to the earthly realm. Parvati endeavoured to locate Shiva, cleansing herself via the act of meditation without clothing in the unforgiving natural environment, ultimately discovering him among the woodland.

According to legend, Parvati is believed to have initially performed the raga, while wandering in the mountains, giving it the name Mal-Kaushik, which means ‘he who wears serpents like garlands’, about a notable portrayal of Shiva. The music pacified his mind, triumphing where all other attempts had been unsuccessful. Shortly after, the couple entered the bond of matrimony. Shiva showed compassion for his defeated enemies by reviving those who were killed and restoring the king to his position of power, albeit with a goat’s head instead of his original one.

Historians speculate that the term “raga” might have originated from a potential amalgamation of “Malavas,” an ancient Punjabi tribe, and “Kaisiki,” a microtonal variation of the note ni (the 7th degree of the musical scale). Regardless, Malkauns is indissolubly linked to its ominously legendary notoriety. Numerous musicians continue to be apprehensive of its paranormal abilities. There is a belief that mishandling it can potentially draw malevolent supernatural beings, as if the essence of Shiva’s Tandav dance is concealed within the raga, ready to be unleashed.

Sarod Maestro Ustad Ali Akbar Khan

Renowned sarod maestro Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, who incorporated Malkauns into his own Raag Chandranandan, advised his students against approaching this raag without the appropriate mindset: “If you are not in a serious disposition, refrain from performing or singing Malkauns. It is imperative that you exercise additional caution when dealing with this raag. This raag is highly favoured by djinns or spirits. If you possess the ability to captivate them – if they appreciate your approach – they will willingly comply with whatever request, you make. If they fail to do so, they will cause your demise. The performer must exhibit patience, striving to maintain a delicate equilibrium that will prevent Pandora’s box from being opened. The devil should not reside in the minutiae. Consider the plight of superstitious performers – while I occasionally feel frightened on stage, I am relieved that failing to execute a modulation would not bring bad luck onto the audience.”

Malkauns elicit a wide range of responses. Spiritual healers claim that it can alleviate headaches and abdominal discomfort. According to reports, some individuals have used it to carry out peculiar experiments on farm animals. For instance, cows housed in shelters were exposed to the Malkaus raga but did not produce additional milk. Nevertheless, the animals exhibited increased levels of activity. The deities of its creation legend were famous for their rigorous acts of self-control, forsaking society and retreating to the wilderness. For many individuals, the raga serves as a summon to pursue a life of austere seclusion. However, for others, the symbolic indicators suggest the other direction. Parvati employed it to stabilise Shiva’s thoughts, assisting him in reconnecting with the real world instead of evading his sorrow.

Malkauns, regardless of the environment, captivates the listener, diverting them from impulsive and deceptive thoughts, and guiding them towards a state of suspended contemplation. It achieves a harmonious equilibrium between serenity and harshness, pacifying Shiva’s destructive dance and prompting him to contemplate the agony he had inflicted. Due to its ambiguities, this piece is distinct and still holds the attention of contemporary audiences.

Rudra Veena

The creation of Rudra Veena is attributed to Lord Shiva, who is believed to have crafted it as a homage to the exquisite allure of Goddess Parvati. According to legend, this instrument, purportedly first played by the deity Shiva, is thought to possess spiritual abilities. There was a belief that the Rudra Veena was too burdensome for the delicate shoulders of a woman. Consequently, women were prohibited from playing it. The Rudra veena has its origins in northern India and is named after the Hindu deity Shiva, who is also referred to as Rudra.

According to certain beliefs, the fabled ruler of Lanka, Ravana, constructed this musical instrument called veena as a gesture of respect for his cherished deity and gave it the deity’s name. According to another account, it is said that Shiva personally crafted the instrument, drawing inspiration from the exquisite appearance of Parvati, his companion. In ancient times, serpents endured numerous hardships. They harboured a fear towards other creatures. They were compelled to find sanctuary in the hermitage of sage Saraba. The sage was a genuine worshipper of Lord Shiva. He would worship Shiva by singing lovely songs. As he sang a certain raga, the snakes were very enthused and commenced to dance.

The serpents gradually developed a close relationship with the sage. They transported water for the puja by holding it in their lips. They excreted a unique fluid that caused the blooms to adhere to their bodies. The sage was greatly surprised by the assistance provided by the snakes. Due to their proximity to the sage, the sarpas implored him to assist them in obtaining a divine audience with Lord Shiva. As per the sage’s desire, Shiva manifested in the guise of a Kapalika and resided in the ashram.

The serpents’ music and dancing persisted. The snakes served the Kapalika because they saw him as a devoted follower of Shiva. Shiva was greatly pleased with the captivating music that mesmerized the snakes and granted them a divine audience. Snakes serve as adornments for Lord Shiva. He is expected to have embellished himself with Naga.

The sage’s singing of a particular raga fascinated the nagas, leading Lord Shiva, also known as Shankara, to designate the raga as Sankarabharanam.

The Saptaswaras

The raga Sankarabharanam is believed to symbolise the adornments of Shiva through its saptaswaras. Sa represents Sarpa, Ri represents Rudraksha, Ga represents Ganga, Ma represents (deer), Pa represents pushpa, Da represents damaruka, and Ni represents nishakara (moon).

This raga provides abundant opportunities for further elaboration. In the 13th century, this musical composition was referred to as ‘Ranjani’. Sankarabharanam is often referred to as the ‘monarch of ragas’. The comparable term in Hindusthani is ‘Bilawal’. In Western music, it is synonymous with the C major key. In Thevaram, this raga was referred to as ‘Pazham Panchuram’. Sankarabharanam has a total of 35 janya ragas, which are its derivatives.

Panini Formulated Sanskrit Grammar

Tanjore Narasayya, a prominent figure in the 18th century, was commonly known as ‘Sankarabharanam Narasayya’. Panini endeavoured to formulate and systematise the principles of Sanskrit grammar in a manner that would endure the effects of time. During his concentration, Lord Shiva manifested himself and rhythmically played his damaru 14 times. Panini, being a genius, comprehended the entirety of Shiva’s message.

Panini recorded the auditory vibrations produced by the damaru and converted them into distinct units of speech known as syllables. These sounds gave rise to 14 syllables, which Panini used as the foundation for developing the rules of Sanskrit grammar. The collection of 14 poems is commonly referred to as the “Maheshwara Sutras” or “Maheshwara Sutrani” in the Sanskrit language.

These verses consist solely of sounds, and when said aloud in one continuous breath, they closely resemble the rhythmic patterns of drumbeats. Due to their origin from a Divine source, these principles of Sanskrit grammar were so flawless and comprehensive that Panini could develop, collate, and codify them in a manner that has remained unaltered to this day.

Co-author Rishi Dasgupta

Rishi Dasgupta, a Masters in Economics from the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, is a millennial, multilingual, global citizen, currently pursuing a career in the UK. An accomplished guitarist and gamer, his myriad pursuits extend to the study of the ancient philosophies and mythologies of India. ‘Adi Shiva: The Philosophy of Cosmic Unity’ is Rishi’s second book as co-author.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

A civilizing read and a reference for the lay reader: thank you.