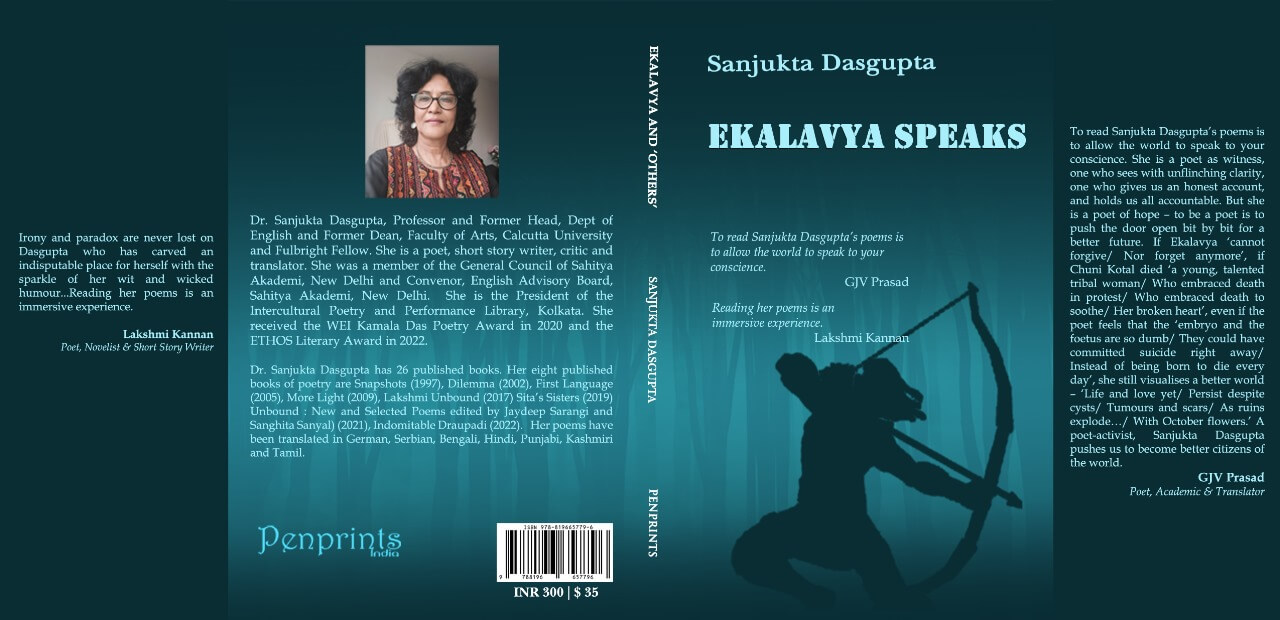

Sanjukta Dasgupta’s latest collection uses ancient myths to expose social injustices, empowering marginalised communities and challenging established power structures, reviews Urna, exclusively for Different Truths.

“Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth's superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —”

~ Emily Dickinson

An elucidation of Emily Dickinson’s classic counsel on the rather complex and multi-dimensional idea of truth-telling per se brings to light the ethos of how one may go about telling the truth. It also illuminates the literary progression of the extended metaphor of comparing truth to the dazzling luminosity, that can only emanate from a gradual yet undeniable opening of the eyes.

Sanjukta Dasgupta’s Ekalavya Speaks takes the leitmotif of the opening of the eyes, many notches higher and leagues ahead, carrying on its able shoulders what it takes to lay bare the foundational truths of our culture, interculturality, and cultural semiotics—the mazes, the alleyways, and the labyrinths. The book deftly moves in and out of how cultural myths shape our worldview, our ideational boxes and behavioural grids, the rotting, decaying detritus of the fabric of Brahmanical hegemony, its belief systems, and why we engage with the world in the ways and manners in which we do.

Ekalavya Speaks spins on the critical hinge of questioning the dogmatic bastions of the unquestionable, the infallible, and the unimpeachable. Dasgupta’s 9th book of poems then is a compelling larger-than-life socio, political, cultural, and anthropological scalpel, an ontological barometer, and an epistemological microscope which through its 86 poems cuts open the deep tissues of subaltern vulnerabilities and humiliations, undertaking a deepened exploration and a scathing excavation to understand the dynamics of systemic otherization.

In her unputdownable introductory note, titled, A Few Prosaic Words, Dasgupta writes, “The received ‘otherisation’ of the subaltern who could never be one of ‘us’ has now been interrogated, deconstructed and redefined. The collective desire and distress of generations of subalterns languishing in the periphery at last has gained significant visibility, dignity, and identity. As a result, it may be hoped that the forms and techniques of discrimination embedded in hetero patriarchy and orthodoxy will be steadily eliminated”.

As a natural corollary, in the eponymous poem Ekalavya Speaks, Ekalavya, who gifts his thumb to Dronacharya and is thus deprived of his essential strength as an archer, is the central mythical symbol, and Dasgupta gives Ekalavya the voice that he had been strangulated of, after centuries and centuries of oppressive silence.

“I was born shorn of privilege

I was born to bend and cringe

I was born to suffer and cry

My being born a tribal prince

A matter of mirth and ridicule

I was born a slave they said

Slavery was my birthright”

(Ekalavya Speaks)

Dasgupta takes her unflinching pen which, figuratively, and metaphorically transforms into a mighty sword of Damascus steel and aims with bulls-eye precision to pierce into the palpable heart of the conscience of the reader, her poetic craftsmanship at par with the unrivalled archery of Ekalavya himself.

Consequently, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” is no longer a rhetorical question suspended and stymied in our collective conscience reeking of the stench of pride and prejudice, for Dasgupta makes the subaltern speak, giving him words of defiance wrapped in seething agony and discrimination.

The foreboding concluding lines: “The Sun Also Rises for us/ I may claim your thumb some day” makes the boiling cauldron of injustice spill over into a new day, asking of its reader the need to awaken to a new world order or else pay the price of a collective outrage as the dominoes start getting tipped against an age-old perpetration of marginalization.

“Sir, why did you take my thumb away

Sir, why did you dwarf yourself

Sir, you are no longer my Godly guru

Sir, you are now my target

Sorry Sir, I cannot forgive

Nor forget anymore.

The Sun Also Rises for us

I may claim your thumb some day”

(Ekalavya Speaks)

Every poem in this collection published by Penprints, India acquires a transformative agency as Dasgupta with her ardent eyes feels her way through the transitoriness and the hollowness of Hindu myths and mythical heroes. Take for instance her astute representation of Dronacharya and the archetype of the irrefutable guru.

“This teacher

Treacherous, traitorous

Equivocator, a pet puppet

Of kings and princes

An Alsatian mind

Guided by his master’s voice”

(Dronacharya: The Teacher of Princes)

Wendy Doniger writes in The Hindus: An Alternative History that “Kautilya makes Machiavelli look like Mother Teresa”. Perhaps to reiterate the irony of it all, Dasgupta’s poem is titled Dronacharya: The Teacher of Princes, making the reader probe into the machinations of kingmakers and the gurus who shaped the career trajectories of princes, often put on ruby-studded pedestals.

Sigmund Freud regarded dreams as “the royal road” to the unconscious, and dream interpretation has thus been an important psychoanalytic technique. Dasgupta helps us analyze the grave underbelly of Dronacharya’s guilt and constructs a haunting imagery of Dronacharya’s sleeplessness, for not even time can blur the ghastliness of some injustices.

“Since that day of mutilation

The treacherous teacher

Could not sleep. Some said

The nagging nightmare of

Hundreds and hundreds

Of blood-smeared thumbs

Spiralling around him

Kept him awake all night.

(Dronacharya: The Teacher of Princes)

Dasgupta takes our deeply entrenched past and brings it to a seismic boiling point, with Chuni Kotal’s Query – a Dalit Adivasi woman from the tribal community of Lodha Shabars of West Bengal, the first woman to graduate from a tribal community, with her searing representation of Chuni Kotal’s voice.

“Ekalavyas and Shambukas

Were depressed victims

Nothing has changed

We are depressed now”

(Chuni Kotal’s Query)

Few poets can capture the fluttering irony of our everyday consciousness and the things that we’d rather conveniently blind ourselves to, like Dasgupta. For in her Hunger in the Metropolis “The stray child and the stray dog” sit side by side on the footpath and share the darkened, abysmal destiny of “Staring unblinkingly at the shelves/Full of enchanting food that they/Would never taste.”

Dasgupta pushes the poetic purview of Ekalavya Speaks, weaving in irony and paradox, and assiduously holds up the swaying crenellations of the challenges of the roles assigned to women, a plethora of gender issues, and the complex notion of identity and the self. To Adrienne Rich is an urgent plea to understand gender far beyond the simple geometry of gender binaries and the reader is reminded to take strident steps “beyond borders” and “to laugh at barbed wires.”

Brian W. Aldiss wrote, “There are two kinds of writers: those that make you think, and those that make you wonder”. Dasgupta makes the reader think and wonder, both, but along with that, question and introspect at a deep, subterranean level as well. Take for instance, when Dasgupta employs the fascinating idea of time travel as Shakespeare and Kalidasa meet, and elevates the poem Shakespeare and Kalidasa to an immersive experience as she unravels the hellish netherworld of a virulent virus, “invisible and ever-present” – a dictator by the name Patriarchy.

Ekalaya Speaks is a tour de force for our times and Dasgupta offers a largesse of intelligence, emotion and invention as she dips her stirring pen into the thickened blood of generational pain through her poetic overt and covert subversion of Hindu mythology and its predominant library of “gospel truths” that have been fed to us systematically as a nation, albeit its shameless perpetuation of caste hierarchies and the employment of “sly-cunning” and “guile” to keep the varnas and castes tightly in their grooves.

If poetry signifies the times we live in, Dasgupta’s poetry embodies the vastness of honesty, the piquant sharpness of accuracy, and the spearhead of fidelity to the searing flesh and the crumbling bones of the human condition.

Dasgupta’s poetry pivots on this quality of utter fearlessness, and as she gradually – poem by poem – pushes past medieval fortresses of mythologies and their archetypes, her poetry transmutes into a catalyst of giving the subaltern a mighty, roaring voice that shakes up the jungles of calcified otherisation. As the African proverb goes, “Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter”.

Book cover photo sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By