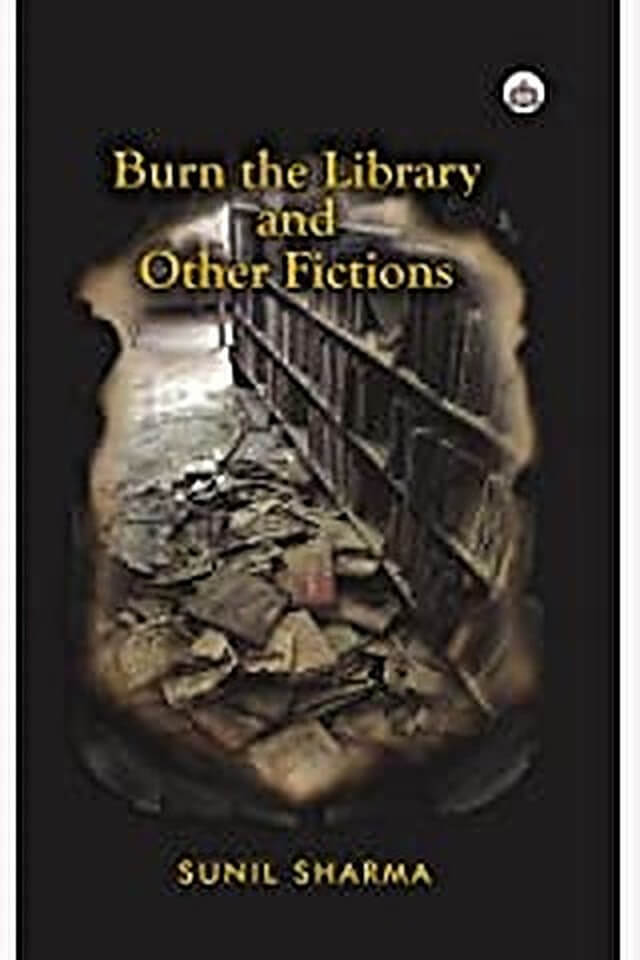

Prof Nandini reviews Burn the Library and Other Fictions by Sunil Sharma, exclusively for Different Truths.

Starting with ‘A Mini Confession’, the camera of this read-at-one-go book is capable of sailplaning you to meadows, woods, landscapes, and cities and then the secret chambers of your heart. Burn the Library and Other Fictions by Prof.Sunil Sharma came to me as a pleasant surprise.

To me, Sunil Sharma is an aficionado of Witness Literature. He is the ‘witness’ to social change, a harbinger of happiness to many a reader and writer. He is no word juggler; he has a social commitment — he believes charity begins at home. I have experienced that more than once when I referred some young writers to him with a small request to help him/her, and without the slightest apprehension, he lend a hand to that person in a big way. I respect him for that, and I admire him for SETU. I read him for his erudite scholarship. I believe his social commitments prompt him to write responsible literature, Witness Literature.

The title Burn the Library and Other Fictions is intriguing. The opening question comes, why does one need to burn the library in the first place? What is this metaphor for burning? There are powerful expressions like “Culture—creativity—reality. If reality sucks, change it. Praxis.” It’s about an app affecting one’s life—virtual reality, endemic cyber navigation clashing the concrete reality. Porn, food porn, selfies—just nothing escapes his eyes. There is a feel of sci-fi in this story. Killing of individual imagination by getting into too much

virtual reality is about ‘burning the libraries’, burning the conscience. Apart from this powerful title story, there are fairytales, fables, and there are here-and-now stories of contemporary truth in this collection. The author is ‘in love with a smile, and his protagonists reflect his personae. ‘Love: Beyond Words’ is a very romantic, very different story. ‘Two Black Stones and an Old God’ is a tale of beliefs and convictions. And there is a

story for the last Duchess—that’s a monologue. Sharma experiments with forms like dramatic monologue — even in his narrative of a short story! The dramatic persona actually recites Browning in the story, and then it has its implications and insinuations. The streets of

Ghaziabad speaks to the author. He certainly is a man of the world. And then, there is the coming of the migrants to the city and the apprehensions thereof. ‘Unseen’ and ‘Skeleton in the Attic’ are multilayered tales. The ‘20-Word Flash Fictions’ are experimental, tentative, novel. ‘New Millennial Love’ is about the post-postmodern scenario. ‘A Story by Teddy Bear’ has some sort of magic realism. ‘The Meeting with Hemingway’ is about age and agelessness—time and temporal. The stories are open-ended—“wolves vs lambs”. After reading the book, I couldn’t stop thinking about Sharma’s characters. They followed me everywhere—to my university, to markets, to malls, to the kitchen, to the garden, to the balcony. I had to; I simply had to write about them to stop them from following me. Sharma has an eye and a versatile pen for flexible, wide-ranging, comprehensive characters. Not a single story has any resemblance with the other—that is the range and scope of Sharma.

Today we witness a paradigm shift in the literary scene, where we question ourselves, is literature all about stimulating the senses? Or does it have a serious and responsible role to play in empathising with the spirit of the common man? Literary studies affect society; it is a generous contrivance that can bring about transformation if literateurs convene on a common platform and make responsible literature. What use literature is during such times of unrest—is the point of debate. Literature is an umbrella term denoting art, culture, intellect, opinions, ideas and thought. Well, the role is remarkable! It can stimulate thought processes and create sharper opinions against or for general apathy. I believe that the written word is the writer’s structure of activism. Too many voices are making a chorus now, leading to pandemonium and mayhem. The politicians, journalists, historians, celebrities, teachers and the new age students—everyone seems to be speaking loud and clear—which is good indeed. So, is the writer’s voice lost in this cacophony? Yes, it would definitely be lost if the voice is impotent, meek and mild. Euphony is the sound of literature, not meekness. The murky links of politics and literature—power politics, the desire to be politically correct—can make literature impotent. The first step to overcome this syndrome is self-doubt. The writer has to be critical about his/her pen and pose the question—does my writing make an impact on anyone at all? During a time when the voice of the mob is overpowering everything else, will my single voice be heard? During an age when the divisions of caste damage society, religion and class, can my pen contest this and be the fabric to connect the disjointed threads? If yes, I must write. If not, it’s better to be the onlooker. Literature is the “inward testimony” of the witness. Witness literature addresses the depths of discovered implications in the pressure of susceptibility, passionate kindness and approachability to the lives of the subjects whom the writers bring into play as the source of their art. Kafka wrote that the writer discovers among ruins “different (and more things than the others)… it is a leap out murderers’ row; it is a seeing of what is really taking place”.

Definitions of the word ‘witness’ in the Oxford English Dictionary is: “Attestation of a fact, event, or statement, testimony, evidence; one who is or was present and is able to testify from personal observation”—thus giving the witness a very responsible and responsive role in any given situation. The term ‘Witness literature’ was used by Nadine Gordimer. In December 2001, Stockholm celebrated the first Nobel Prize’s centennial. On this occasion, the Swedish Academy organized a symposium on the “Witness Literature” theme. Lectures were delivered by speakers from Asia, Africa and Europe, including three Nobel laureates in literature, Nadine Gordimer, Kenzaburo Oe and Gao Xingjian. It is a reasonably new concept in the literature that examines the complex association between the author and the reader. Witness literature entails a harmony between the reader, the text and the writer –which is practically not possible in other forms of literature. It creates a genre of events that expects witness, as opposed to simple surveillance, or even simple understanding, from the part of the writer. The writer has the capacity to blend his/her personality with the chronological essentials of an event and create witness literature.

The critics may question whether there is a loss of creative autonomy in witness literature. Is it too much didactic literature minus any artistic liberty? Is art only for life’s sake? What about art for art’s sake? What about the cerebral pleasures in art? What is the difference, then, between art and theosophy? During a time when social media, TV and the Internet have taken over, are reading habits still intact for us? Can literature practically help to overcome the chaos that we are facing now? Is literature bridging the cross-cultural

segregation? Why is the uncomplicated country India missing from the literary scenario? Are the writers truly empathetic witnesses to the life surrounding them?

Burn the Library and Other Fictions by Prof. Sunil Sharma addresses some of the above questions—he assimilates art and life in the most balanced way while taking care of the aesthetic value of art. After reading his short story collection, the food for thought comes to me from Albert Camus: “The moment when I am no more than a writer, I shall cease to be a writer.” Sunil Sharma is not just a writer; he is certainly much more than that—he is the ‘witness’ to social change, towards a healthier and better knowledge society.

Works Cited:

- Sahu, Nandini. Responsible Literature, Witness Literature, CSR VISION, Vol. 4, Issue 12, April 2016

By

By

By

By