Dr Ranjana explores the various layers of human relationships, wishes, longings and disappointments with sensitivity – exclusively for Different Truths.

The retired life of Mr Sharma was in search of Sylvan surroundings, far from the madding crowd of Mumbai. After his retirement, many of his friends suggested that several avenues were available, and he could utilise his skills and experience by getting a positive engagement. Working after retirement was a good idea as it helped stay physically and mentally healthy and provided an additional source of income. He could also find a job in his specialised field. But it was a personal choice, and he didn’t like to continue working after retirement. He didn’t want to go to his son, who had settled abroad. He was aware that a feeling of worry might lurk at the back of his son’s mind for having left his parents in India. So, Mr Sharma didn’t allow his sense of guilt to linger and assured him during a video call:

“Your mom and I will both be secure and happy; don’t worry. Our small city has the facility of air connectivity. We can come whenever we need to. There is domestic help, too.”

It was true that he wished to enjoy the peaceful phase of his life …

It was true that he wished to enjoy the peaceful phase of his life and what could be more inviting and suitable than his native bungalow that abounded in trees and groves. It offered a comfortable and quiet space and the surrounding where he could curl up with a book or pursue hobbies.

There was a time in Mr Sharma’s life, quite a few years ago, when he was fond of city life and used to go into the universe of parties and get-togethers with his wife, Shalini. She was an expert in hosting a dinner party, and they had created a good community of friends. There was little talk about being gluten-free or strict vegetarian then – everyone was happy with traditional barbeques, kababs, sweets, and savoury and tasty bites. Her skill in crafting salads and preparing non-veg dishes compelled admiration. One could only marvel at how she dressed up food and snacks – fine china made them taste fantastic. Also, there was the perfect wine to match them; on these occasions, Shalini used to bring out her crystal goblets and glasses. After the dinner was over, the couple rejoiced in the perfect and fun-filled moments:

“Shalini – the culinary connoisseur!” was the remark of Mr Sharma, and Mrs Sharma answered with a smile: “Well, don’t butter me up, Sudheer!” Mr Sharma knew she chewed his words with great relish in her heart.

Memory, nostalgia, and longing – the triad- played in his mind. The familiar landscape of summer!

Mr and Mrs Sharma were visiting their native place after a long time. The cab had left the airport, and Mr Sharma was enjoying the ride – towards his old home, a series of evolutions and memorable moments! Mango and lychee trees were on both sides of the road, laden with fruits. He grew up in Bihar and nurtured memories of being able to enjoy the luscious fruit almost straight off the tree. The lychee season overlapped the mango season from May- June. Memory, nostalgia, and longing – the triad- played in his mind. The familiar landscape of summer!

“Have you planned the renovation properly!” asked his wife.

“Yes, of course! That day we had discussed the points – remember?” Mr Sharma replied.

“Before we translate our ideas into reality, there are a lot of things to consider – how to find a good contractor, how to mitigate costs, how to revamp a space to make it more functional and beautiful,” Shalini said all in one breath.

Mr Sharma listened to her and responded, “Everything will be done so that our bungalow regains a good condition. I have a variety of decor ideas for this purpose. We should concentrate on choosing a colour scheme because colours can transform a plain room into a unique space. But selecting the right palette sometimes becomes challenging.

“Oh yes! I think the same way,” came Shalini’s thoughtful reply.

The news of the arrival of Mr Sharma spread like wildfire in the vicinity.

The news of the arrival of Mr Sharma spread like wildfire in the vicinity. The caretaker of the bungalow told Sukhram about Mr Sharma’s decision to stay in the house and renovation was needed. Sukhram was a daily wage worker, and his grandfather was a cultivating tenant in the cultivation of land belonging to Mr Sharma’s father. He was one of the favourite persons of Mr and Mrs Sharma because he was sincere and trustworthy. He was excited at the prospect of renovation of the bungalow – the process meant a torrent of wages and opportunities for so many days, nay months. There would be so much to do as a helping hand in construction, cleaning, painting and much more. After the renovation work was over, he could even ask for a suitable job from Sharma Saheb – maybe a gardener’s job.

Sukhram had experience preparing construction sites and loading and unloading materials and equipment. Lean and muscular, he could quickly build and take down scaffolding and temporary structures. But he was apprehensive about the future. His work involved a lot of uncertainty and a lot of risks. He didn’t know much about International Labour Organisation or labour laws in India, but he wished he had money and security in future. How long would the struggle last? His anticipatory anxiety disturbed him, like the sounds of sirens in the night making him wake up multiple times.

Sukhram has had a hard time making ends meet. But he didn’t let his wife work as a labourer. She did the household chores of an old widow as a domestic help instead. Sometimes she did cut and weed in paddy and wheat fields. He was aware of the abuse and sexual harassment of female workers by contractors on sites. Also, he didn’t leave his native place to become a migrant worker because the migrants were more vulnerable to risk and exploitation. He remembered his friend Sampat who had gone to Delhi and never returned – he died after falling from a height, and his family members were hardly informed. His mother kept taking his name and ran on the road wiping her tears: “Sample, my son… my son… how long will I live without you? O, God!” She died soon after. There were a lot more harrowing details to be shared.

It had been boiling since morning, and the heat did not subside even at night.

It had been boiling since morning, and the heat did not subside even at night. Sukhram squatted on the floor beside his wife, Urmila, sweating from the intense heat. Their children were sleeping on an old cot. The mosquito net was torn, and mosquitos were highly abundant. Hundreds of them had gone inside the net, and Urmila could hear the buzzing noise. She was trying to crush them between the folds making little smudges on the net and the faded bed sheet. “A cursed nuisance!” She muttered.

“Urmila, I have good news for you – Sharma Saheb and his wife have come from Mumbai to stay here in Muzaffarpur,” Sukhram said happily.

“So what?” Urmila asked curiously.

“They are going to makeover their old house with modernisation – some new constructions, repairing and painting…easy work opportunity for months. And you know Sharma memsahib is kind enough; she may provide a meal for me if I work there on daily wages,” Sukhram explained to his wife.

Urmila was glad to hear Shahram’s words because they filled her heart with the hope of getting something. She said, “Rinki ke papa, you know, for a long time, I have been thinking of having a few big containers to store the wheat berries and some other foodgrains. No need for rice storage because we seldom have more than a handful of rice. Empty paint buckets are perfect containers – you can also use them for carrying and storing water. Saheb’s bungalow is going to be painted, and you can manage to get a few for me and….”

“Yes, I understand what you want to say,” interrupted Sukhram and added, “of course, so many paint buckets will be empty. Still, I have worked at so many sites and found that whenever painting work is in progress, everyone keeps trying to grab the empty boxes – they are so useful after all – the bigger the bucket, the bigger the fight!”

“Fight?” Urmila asked in surprise.

‘Not really, but all eyes are on the paint buckets – small, medium, and large sized; twenty-litre vessels are in great demand!” Sukhram said, rolling his eyes.

Urmila dreamt of big empty paint buckets till late that night – an array that gave her happiness and relief.

Urmila dreamt of big empty paint buckets till late that night – an array that gave her happiness and relief. Rainwater or moisture seeping through the leaky roof would no longer be a problem. Last year there was fungal damage and caking in grain and flour; wheat had sprouted in the small sack. All the grains that were there were gone. In her childhood, she had seen her mother use a particular earthen container she used to get from the potters in the village, which were very cheap. But now, such things were few and far between.

The day dawned crisp and clear. Sukhram’s old decrepit house was bathing in the soft light. As the rays fell upon the mango tree in his backyard, the twigs and the green raw mangoes sparkled like solitaires. So many shapes were created by the dappled light coming through gaps in the canopy. The sun was going to change its mood at noon – blazing like Titan’s fiery wheel in the sky.

Sukhram was in his backyard looking at the white pinwheel flowers and the red hibiscus planted by his mother years ago …

Sukhram was in his backyard looking at the white pinwheel flowers and the red hibiscus planted by his mother years ago – rugged, aged, and beautiful. He loved tagars and arhuls but was sorry that native flowers were disappearing. Hybrid flowers were fast replacing desi varieties and hence were getting restricted to the landscape of temples and villages. The faint scent of the white tagars was very much there, pulling him close to the memory of his mother, but before he could be lost in thought, he realised that he had to go to Sharma Saheb.

Mr and Mrs Sharma sat on the veranda furnished with brown chairs. They seemed to be relaxing in a pool of shade. Soon they saw Sukhram coming toward them.

“Pranam, Saheb; pranam Memsaheb!” Sukhram greeted the couple.

“Pranam, pranam,” Mrs Sharma smiled at him.

“Tell us how you are,” she asked, adjusting her gold frame eyeglasses. She loved the look and feel of light-shimmering glasses.

“So-so… somehow, I’m managing my family,” replied Sukhram.

“How are Urmila and your children? How old are they?” asked Mrs Sharma.

“Memsaheb, my daughter Rinki is thirteen years old, and my son Manish is just eleven. Both go to school and take an interest in studies,” replied Sukhram.

“Very good,” said Mrs Sharma.

“I want that they should complete their studies and settle well in life – never like me!” said Sukhram with a horizontal hand movement.

Indeed, it was the wish of Sukhram that his children must have a promising future.

Indeed, it was the wish of Sukhram that his children must have a promising future. Mrs Sharma was amazed at his care and concern. After a few minutes, he asked, “Memsaheb, when will the work start?”

“Very soon – in a few days,” replied Mrs Sharma. “You will work as one of the helpers on daily wages,” she continued.

Sukhram folded his hands gratefully and requested, “when the bungalow is painted, so many paint buckets will be empty. Memsaheb, please ask them to give me a few ones so that I can store grains and water.”

“O, why not? The area of my bungalow is huge, and the number of empty buckets will be large. I’ll tell the contractor, but you should also tell him about it. You must have had an experience that most people – workers, painters, and everyone else– keep trying to get these containers. When getting my Krishnanagar flat painted three years ago, I told the contractor to give two small buckets to the kamwali bai, but he misled her, and she couldn’t get the dabbas.” Mrs Sharma replied, revealing the facts.

Sukhram continued to give nods of approval as Mrs Sharma talked.

Sukhram continued to give nods of approval as Mrs Sharma talked. Mr Sharma was flipping through his phone messages; in between, he looked at the magazine in front of him on the classic cane table that brightened up the space. He was not interested in Sukhram’s talk – such little things meant nothing to him. He was busy thinking about the scheme of colours for his home – the look and the feel of beautiful blooms!

“Memsaheb, now I’ll leave. It’s so nice that both of you have come here.” Sukhram asked permission to go.

“Come tomorrow to clean weeds and grass of the compound. And yes, Peepal plants have grown at many places on the walls and should be destroyed before they create cracks,” said Mrs Sharma.

“Very well,” said Sukhram, leaving the place thinking about the coming days.

The home repair and renovation went on for months, and painting work was taken up that day – a much-awaited day for Sukhram. Expert painters were working under the instruction of the contractor. Sukhram was there to help them with odd jobs. Before painting and patching, walls were cleaned, and dirt and grease were removed. Steps were being taken to prep the walls to prepare the actual painting. Putty, paint, brush, roller, and other paraphernalia were stacked in a small room to be taken out as needed. Sukhram’s mind was preoccupied with the thought of empty paint buckets – his hands were working, though. He was looking for an apt moment to ask for the same.

The contractor was moving around onsite, giving the impression of being extremely busy.

The contractor was moving around onsite, giving the impression of being extremely busy. Sukhram saw him and cleared his voice to speak, but the words delivered by him were like a premature baby – weak!

“Thekedar Saheb, please manage a few empty paint buckets for me, too – the bigger ones. I have already told Sharma memsahib about it, and she assured me that I would get them,” Sukhram beseeched.

“Sukhram, don’t be jealous. You’ll have them when the time comes. You’re not a special person to whom the stuff should be given. Memsaheb didn’t tell me anything about it. The next moment he added, “Pata nahin kahan-kahan se chale aate hain aise log…” (Not sure from where all such people come).

Sukhram felt like retaliating with equal rudeness, but he knew it would make things worse. Therefore, he pocketed the insult with a calm facade – anger raging inside! He could feel the churn of suppressed anger and resentment: what does the corrupt contractor think of himself?

The selfish community takes advantage of labourers by denying proper wages and often threatens them …

The selfish community takes advantage of labourers by denying proper wages and often threatens them with dire consequences if they open their mouths. That day he was caught sleeping with a construction worker’s wife, Ramsakhi, in the nearby village, but somehow, he managed to get away…The storm continued in Sukhram’s mind, and he was trying to control it. But soon, another verbal attack triggered the adrenaline rush into his bloodstream: “Arey Sukha, what happened? What are you thinking?” The contractor smirked, revealing his stained teeth botched up by gutka.

“Don’t waste time standing and doing nothing…you have to work…go… twenty-litre containers… beggars are not choosers!” Remarked the contractor sarcastically and laughed, “Ha-ha!”

Sukhram felt a colossal rage surging in his chest. He couldn’t help biting back a sharp retort, come what may!

“Stay within your limits, understand?” Sukhram countered, pointing his finger at the contractor.

“Don’t outgrow your jacket, Sukha! I warn you!” He growled.

“You…you don’t outgrow your jacket, what’re you? What will you do? You were a migrant worker a few years ago – hungry and wretched with your wife at the construction sites in Vishwakarma Nagar, Delhi. By dishonesty and cunning, you tried to become a big man… so-called, of course! You lured simple village labourers with the prospect of better opportunities and made them migrant workers on low wages. You earned with the cooperation of the agents…and…” Sukhram’s pitch went higher.

“I said shut up!” The contractor raised his hand to beat him. But Sukhram took a step forward, held his hands tightly and pushed him back. The shouting and ranting went on. Before the ongoing argument turned violent, the painters and labourers came up to appease them. They were afraid that it might affect their work and wages. One of them ran and called the Sharmas, and the fight was resolved after their intervention. But the scathing remark and behaviour of the contractor made him smoulder with resentment; fury kept vibrating through his being, and he left the working site.

Urmila was surprised to see Sukhram come early that day as she opened the door for him.

Urmila was surprised to see Sukhram come early that day as she opened the door for him.

“How have you come so early today?” She asked.

Sukhram didn’t answer and came inside. Urmila was eager to share her thoughts and doings. She said: “You know, I’ve been busy arranging and rearranging the utensils and other things we kept in the kitchen. I wanted to create space for the buckets we will likely get… I’m waiting…waiting…” Urmila chirped, pointing her finger to the small, dark space that served as their kitchen and store.

Suddenly she looked at Sukhram, who had come silently and was sitting on the worn-out charpai (string cot). Her happiness was gone.

“What’s the matter? Tell me; you seem to be in a bad mood. Why?” Urmila asked anxiously.

Sukhram didn’t answer. He looked in the other direction with a frigid stare; his face was grim, and Urmila knew the news wouldn’t be good.

“What happened?” She asked him again.

“Today, I got into a quarrel with the contractor – angry arguments on the verge of violence. I felt like giving him a bash on the face but couldn’t. He never likes me because I know about his evil deeds,” Sukhram stated.

“But… but, what was the reason for the quarrel?” Urmila was impatient to know.

“The bloody paint buckets – yes, the empty ones!” Sukhram spoke loudly and added, “beggars…beggars…beggars… we’re big damn beggars… poor…uneducated!”

Whenever Urmila tried making sandcastles at the beach of her life, they were swept away in the tidal destruction of destiny.

Whenever Urmila tried making sandcastles at the beach of her life, they were swept away in the tidal destruction of destiny. She was lost in the brooding landscape of mind and the curvy roads of heart. As the better half, she had delved deep into the innermost recesses of Sukhram’s heart umpteen times and felt the hidden nerve. Since childhood, he nourished a desire to get an education but remained a middle school dropout compelled to take up the job of a labourer. The dormant desire in the periphery sometimes woke up, and his self-esteem manifested in anger and frustration. She knew he could do much better in life. But there was no point thinking about it.

There was silence for about half an hour, and then Urmila suddenly spoke up, “Why don’t you let me work? I want to take up the job of a daily wage labourer. I still have a lot of time left after doing household chores. What do I get from working at auntie’s house?”

Urmila’s healthy-meaning words were just like fingers on an exposed wound. “What are you talking about, do you know?” Sukhram questioned her.

“Yes,” answered Urmila in a calm voice. “How will this money problem end? Tell me! Children are growing up.”

“Let it not end – I’m not going to let you work with the people rotten to the core!”, said Sukhram sternly.

“But don’t you see we can’t even get essential things in life?”, retorted Urmila.

“How many paint buckets are you pining for? Tell me…tell me! I can manage to procure hundreds of them,” he yelled as a man possessed.

“Don’t behave like a child, Rinki ke papa. It is impossible to even in seven births – jo muh me aata hai aap bak dete hain bina soche samjhe! Dhut! (You utter mindlessly without giving it a thought).”

With a crestfallen face, Sukhram came to his senses and realised the futility of his talk …

With a crestfallen face, Sukhram came to his senses and realised the futility of his talk and temper that had come roaring like a sudden, strong gust of night wind. He wanted to relax and looked through his small window: the blazing midday sun had softened its stance. Sukhram looked at his watch – it was time for the children to get back from school. He reflected on them – his baskets of love and joy, his vessels of rainbow colours! But soon, his mind was filled with clouds of despair – rainbows need sunshine – how much sunshine can be in the lives of poor, struggling people?

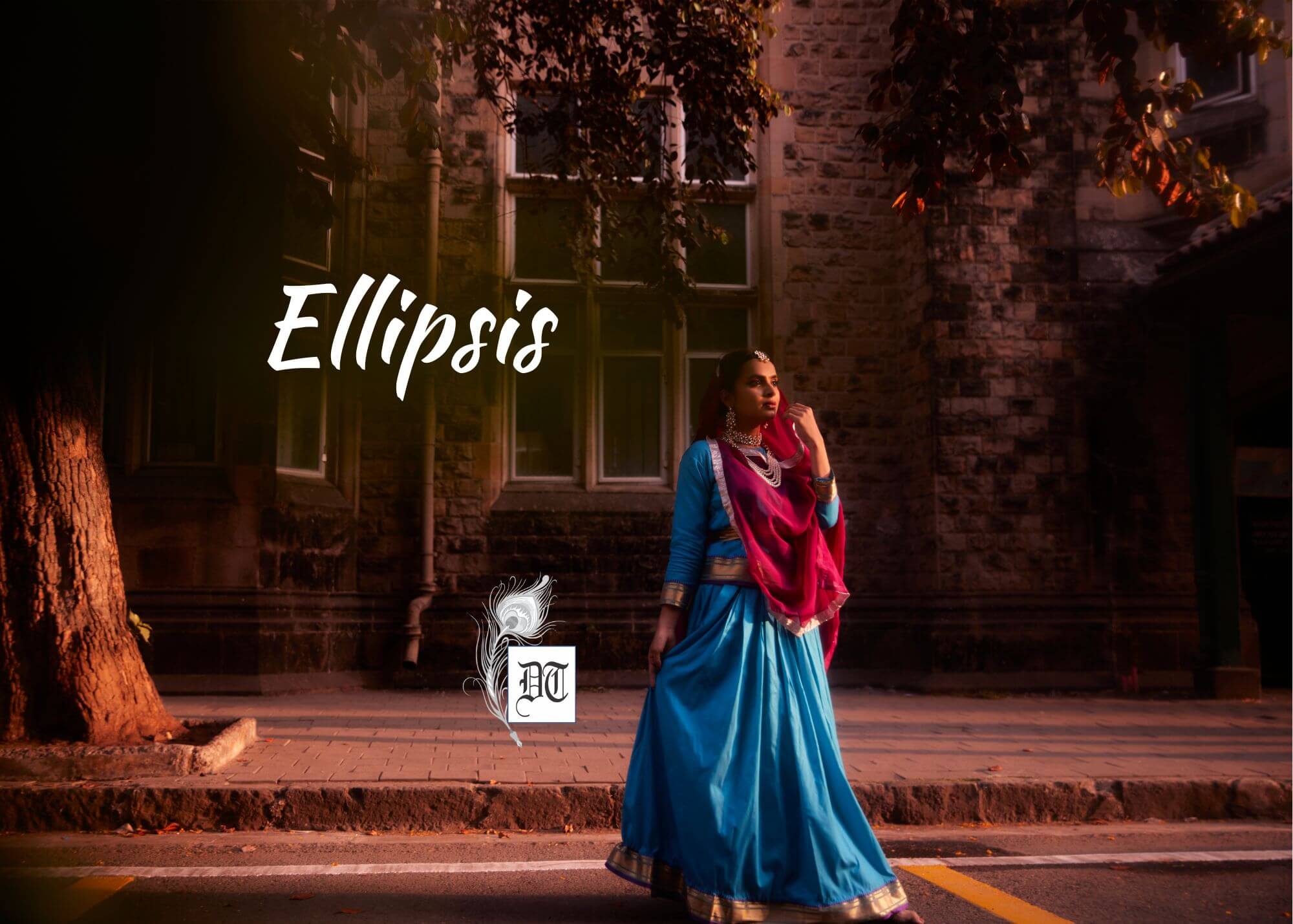

Picture design by Anumita Roy, Different Truths

By

By

By

By