Dr. Roopali walks down the memory lane and recollects life of an army brat in a desert. A book extract exclusively for Different Truths.

One day, after six months the tiny Blue Mountain train chugged us away from the giant olive tree under which Porridge and I and Padma of the Pigtails had spent many afternoons. The sun picking olives as big as marbles dropped by. The wind whooshed through its branches full of dark green leaves.

Miss Haley, our tutor, told us that the Greek Gods who live on a mountain called Olympus love the green olive berries. They are not sweet.

Cook, Bearer, Paapa the Sweeper Boy, Chinamma, Paapa’s aunt from his mother’s side, Irti, Shanti, and Dhobiman wore their best old clothes and stood in a straight line on the railway platform at Connor, Wellington.

Say Goodbye

They shook our hands just like English people. They came to say goodbye. Just as the train blew its long “I am leaving” whistle, the straight hand-shaking line broke into weeping pieces of Cook, Paapa, Chinamma, Irti, Shanti, Bearer, Ramulu and Dhobiman.

…they said bye-bye to us just the way we do as Indians. Like when someone has died.

Clutching Mother, touching Dad’s feet, slapping their foreheads where they keep their Kismet, holding Porridge and me to their thin black chests, they said bye-bye to us just the way we do as Indians. Like when someone has died. We cried too. We cried very hard, too.

We were off to where the desert burns like the fire in the choolha in the Cook House built in1856. Little England in the cool-cool Blue Mountains left us. From the train window I could see them run back. I said “stop-stop”, but they just did not.

A Small Desert Town

Dad and his battalion arrived with us to a small desert town. The people here were tall, and the sun had baked them like dark brown chocolate.

The women wore big skirts like Queen Victoria, but they were mostly bright yellow and red.

The women wore big skirts like Queen Victoria, but they were mostly bright yellow and red. Some of them covered their faces. The men had big red and yellow cloth wrapped on their heads making the heads look really big. This way the sun can’t burn holes into their head from where their brains will drop out. Nobody cares if the sun makes holes inside the women’s heads.

An Old Palace

The house we were to live in was an old palace. The old Maharajah’s commander-in-chief, the Senapati, lived here till some ten years ago. The Maharajah now lived in Raj Mahal, the City Palace.

When the English who were King makers went back to their own ice filled land, the Palace had fallen into disuse.

When the English who were King makers went back to their own ice filled land, the Palace had fallen into disuse. The Indian Army used it to train its new soldiers who came in great excited numbers.

Senapati House

The Palace was named Senapati House after the commander-in-chief of the Rajah’s army. A new battalion in town made the palace alive again. Its grounds spread over miles of land. There are no Olive trees here. No squashes or pimentos. Not even the droopy pear-shaped squashes, which hung low behind the Cook House built in 1856. The ones that grow here belong here. They are not strangers in this land. They feel quite at home.

The jungle jalebi with its twisted pink and white fruit is called “angreji jalebi.”

So many neem, guava, amla, shahtoot, sanjana, imli, jamun, and wild nimboo trees grow here. Also, keekar, ber, and karonda. The jungle jalebi with its twisted pink and white fruit is called “angreji jalebi.” The English people couldn’t make a little England here.

To reach the palace you have to run up twenty stairs. The stairs are so wide that 50 people can run up to the palace together! When the Senapati lived here, musicians carried their musical instruments across the desert where there is no water. Their music melted the clouds and brought down some rain, and some bajra grew.

The Palace

Out of the one hundred rooms in the palace only 15 can be used. The others are locked. The floors are made of white marble and the furniture is soft with velvet cloth. The chairs have high backs called Victorian, which the Rajah’s dad, the Maharajah brought with him from England. He would go there every year to meet other maharajahs who would then go to meet the Queen.

Rows of horse houses called stables watched quietly as the palace became a house.

Rows of horse houses called stables watched quietly as the palace became a house. The Senapati’s guests used to stay in the houses around the palace. He loved parties and sometimes invited the Maharajah.

There are dark cold rooms underground where many bats hang upside down. Porridge says the bats can see an upside-down world. Porridge and I flash torch lights on them.

Summer Sandstorms

Summer sandstorms hide the hot sun. Its eyes are full of red blood. The howling winds blow the desert in through windows and doors making small sand hills on the marble floors. Porridge and I run barefoot through the halls. We run past pillars where the scream of the peacock follows the slithering snake. The crow who wore a peacock’s feathers must have lived here. The grass and forest bramble are covered with one eye peacock feathers dropped by peacocks walking about. There are many peacocks and there are many crows.

Langoors with long tails and burnt faces swing from neem tree to keekar tree.

Langoors with long tails and burnt faces swing from neem tree to keekar tree. They love eating the sweet fruit of the bitter neem. The baby monkeys look very old, and they hang under their mothers. The mean dad monkeys have red bottoms, faces black like the coal Cook used in the Indian oven in the Cook House Built in 1856. They walk casually across to the kitchen door to snatch rice, bananas, or bread.

Snakes Sneak

Snakes sneak across to the house and curl up under cosy cool pillows. Flying snakes whoosh fly from one end to the other. Cobras hiss in low tones and Rattlesnakes carry their own rattle at the end of their tail. They noisily announce their arrival. A frightened Porridge makes Mother sleep with her.

“You girls are growing up. You should start reading some school books now,” Mother said. I looked at Porridge. She hasn’t grown an inch. We miss our faraway home in the blue mountains.

There nobody ever said we had to grow up.

There nobody ever said we had to grow up. Here the shady neem tree with its bitter leaves and sweet fruits spreads its branches to give shade.

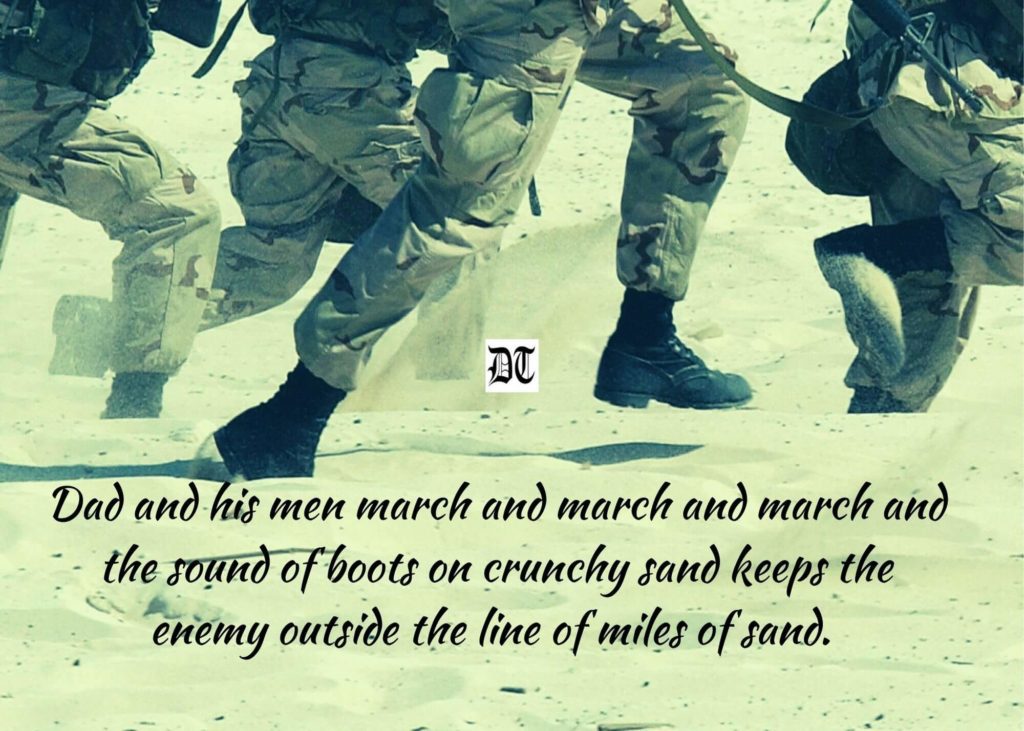

In winter the desert is ice cold at night. Dad and his soldier men march across the sand dunes with their feet like blocks of ice in the kitchen ice box. LeftRightleftRightLeftRightLeftRight they go, leaving frozen footsteps on the icy sand. They return LeftRightleftRightLeftRightLeftRight.

Heavy Black Boots

Mother tugs at the heavy black boots on Dad’s feet and powder dew falls out with tiny heaps of sand. The twinkling stars twinkle happily. Jackals howl in the distance where the sand stretches into nowhere. The shepherds who saw the star when Jesus was born lived here.

Jackals see and hear and smell much. Their ears and nose and eyes can find out if there are other people around in the dark.

The three kings had come across this desert. The enemy isn’t far away. They are just as far away as from where the Jackal howls can be heard. Jackals see and hear and smell much. Their ears and nose and eyes can find out if there are other people around in the dark. They hear the rifles and the powder in the air. That is why they howl a fearful warning to their folks. Dad and his men march and march and march and the sound of boots on crunchy sand keeps the enemy outside the line of miles of sand.

Survival Mantra

Dad’s best friend Uncle Jehangirwala says, “The English have left this festering sore with instructions to nurse it. Both this side and that side. We have inherited it like a deadly disease and nurtured it like a promise. We don’t want to be friends with our enemy across the line. Only by remaining enemies can we survive. That is the Survival Mantra. Friendship will destroy us. It will ruin the reason for our existence. And we have promised to keep it this way. And we don’t want to be promise breakers. Promise breakers burn in everlasting hell fires. Gun fire isn’t so difficult to face. At least there is opportunity for heroism.”

The soldiers must listen to the fat minister.

It is October 2nd, and it is Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday. A fat minister is shouting over the loudspeaker. The soldiers must listen to the fat minister. Dad and uncle Jehangirwala are muttering. “These dhotiwallas will ruin the country!” So many people in white-coloured clothes are wearing topis. They have come with the minister. Porridge says the cap is called Gandhi topi. Some people blame Gandhiji. They say if it hadn’t been for these Gandhi topiwallas this country wouldn’t have got into this mess. Porridge says, “How come people who wear Gandhiji’s Topi are not like Gandhiji?”

Mother cleared this matter real fast. “Because Gandhi never wore any such topi.” Somebody is telling lies. If I wear such a magic topi, I can tell some real good lies and not be caught.

An excerpt from Dr Roopali Sircar Gaur ’s forthcoming novel Porridge & I. The narrator is an eight-year-old child growing up in recently post-colonial India.

Visual sourced by the author and by Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Wish you good luck for your new book Porridge and I.

I have read the excerpts and very much exited to have a copy when the book is released.

It’s a story of what defense children go through in remote areas of a Vast India

with varired flaura n fauna.

I could picture Mom’s reading this out to children, as they slept talking of sand n boots n the round jaleybee imlee

That each of us goes to pluck in our own yards. N above all I loved her friends name-Porridge .

Great reading Roopali,children n parents are going to love this Story

Porridge & I