It is sacrilegious to criticise any work by the triumvirate, Bankim, Sarat and Rabindra, and an immediate fatwa is declared on any ordinary mortal who presumes to do so. Here’s a contradictory view by Soumya, exclusively for Different Truths.

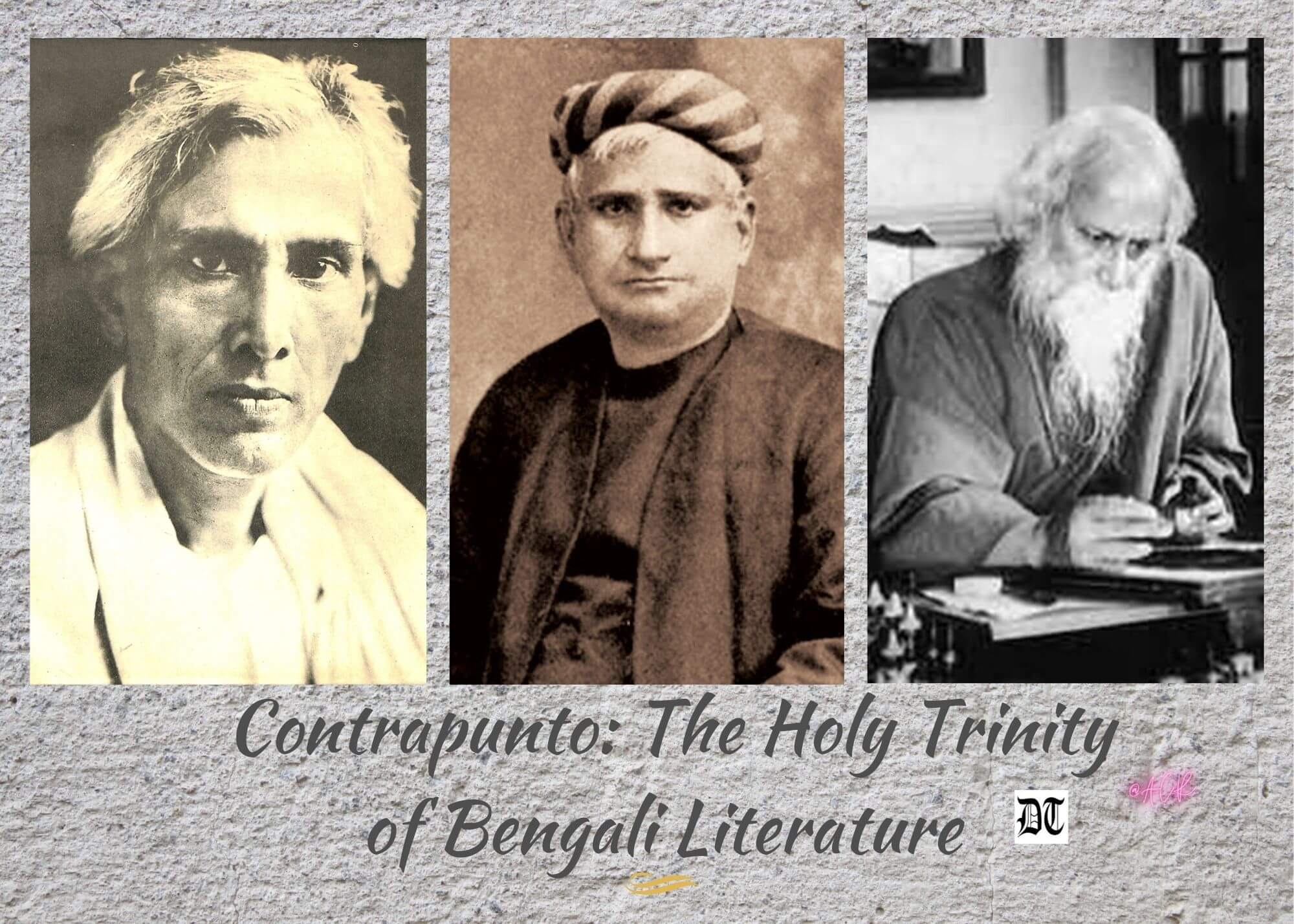

For every true blooded Bengali, whether by birth, adoption or naturalisation, there is a holy trinity of Bengali literature – Bankim, Sarat and Rabindra: The Brahma, Vishnu and Maheswar of the literary pantheon. It is, therefore, by definition, sacrilegious to criticise any work by the triumvirate, and an immediate fatwa is declared on any ordinary mortal who presumes to do so. This has been discovered by numerous contemporary lesser litterateurs and has recurred over various generations. Buddhadev Basu and Sunil Ganguly and other enfant terrible over the ages have suffered this fate.

This fatwa extends to any research into their personal lives as well, unless it is to establish, and they were abstemious saints with impeccable conduct, which would not cause a Victorian matron to frown. Any evidence to the contrary is a work of the devil incarnate.

This fatwa extends to any research into their personal lives as well, unless it is to establish, and they were abstemious saints with impeccable conduct…

Given such a healthy atmosphere of debate, it is no wonder that most criticism is largely emphasising their greatness in life and literature, finding new evidence to corroborate the existing thesis, and sometimes, in less skilled hands, amounting to hagiography.

So, when a cursory reading of Bankim by today’s youth gives the impression that it is a series of historical romances for the young adult, although no doubt a pioneer in the genre as far as Bengali is concerned, but already well established in Europe, and not finding much value other than archival, he keeps it to himself and looks for new ways to discover genius.

A similar perusal of Sarat Chandra will no doubt indicate a goldmine of plots for Bollywood and Tollywood tear-jerkers…

A similar perusal of Sarat Chandra will no doubt indicate a goldmine of plots for Bollywood and Tollywood tear jerkers, as they have spawned more screen adaptations than any other body of work, A vast output of soaps on the small screen have the same inspiration. Now, no one has accused soaps or pot-boilers of literary genius, but the prime inspiration is the holiest of holies.

Attempts by a few brave souls to re-interpret the themes to today’s values have been met with war cries by the purists. Although the likes of Buz Luhrmann and his ilk have re-interpreted Shakespeare beyond recognition and our own Vishal Bhardwaj amongst others have undertaken similar projects with great success, even mild digressions of the plotlines of our holy trinity to match today’s sensibilities results in calling for blood from the upholders of our cultural heritage.

This results in condemnation without contemplation of celluloid gems like Dev D or Rituparna’s Chokher Bali.

This results in condemnation without contemplation of celluloid gems like Dev D or Rituparna’s Chokher Bali. Ray, being a modern-day saint of the Bengali cultural pantheon, escapes the worst harangues for his occasional re-interpretations as in Ghare Baire or Teen Kanya.

So today, if a perusal of Bankim Babu or Sarat Chandra leaves the lay reader cold, we blame it on the lack of our intellectual depth, rather than the possibility that although they were pathbreaking works in their time, their value or relevance may have dimmed with age.

Tagore, however, is a different ball game altogether.

Tagore, however, is a different ball game altogether. The genius of his poetry, music, stories, drama, political thought and art have become far more evident in retrospection than was suspected in his lifetime, the Nobel prize notwithstanding.

Even so, in order to understand him and his work from today’s perspective, freedom to criticise is a pre-condition. Tagore himself recognised this and the only contemporary critic who Robi Babu dared was Tagore himself, in the persona of Amit of Shesher Kobita. Here Amit suggests that contemporary poetry – remember, this was Tagore’s own lifetime – should be like that of ‘Nibaran’, who also was a creation of Tagore. Thus, he himself showed alternative styles of poetry under this pseudonym and encouraged his diffident contemporaries to think beyond Tagore.

Despite this clear carte blanche, till today, it takes a brave soul to be publicly critical of Tagore…

Despite this clear carte blanche, till today, it takes a brave soul to be publicly critical of Tagore, a la Amit of Shesher Kobita.

I was, therefore, surprised to hear during a book reading event by the crossword prize winner Neel Mukherjee, who had done an inter-textual interpretation of Ghare Baire from Miss Gilby’s point of view, that he did not consider Tagore a novelist.

This was a view I had secretly held and did not dare to air till, supported by a published author, I will attempt this now.

Tagore’s short stories were brilliant in the classic mould of the short story, but the novels were a different matter.

Tagore’s short stories were brilliant in the classic mould of the short story, but the novels were a different matter.

The traditional concept of the novel, where the interplay of an array of finely etched characters brings out the nuances of their personalities, a drama unfolds, conflict arises and is resolved. Dickens, Hardy, Hugo, Zola, Flaubert, Thackeray, Scott, Collins, Austen, the Bronte sisters, Eliot were the role models and Bankim, Sarat, Bibhuti Bhushan, Premchand were our classic models.

Tagore’s novels, except for Chokher Bali, do not fit in.

Ghare Baire is a brilliant debate on the morality of nationalism and end versus means, and way ahead of its time…

Ghare Baire is a brilliant debate on the morality of nationalism and end versus means, and way ahead of its time, a major critique of narrow nationalism, the Congress, and Gandhi’s methodology.

Char Adhyay is a debate on violence versus non-violence, extremism versus moderation.

Gora is about insularity, prejudice and tolerance, tradition versus reason, validity of ethnicity and race.

The masterpiece was Shesher Kobita – an enquiry into the nature of aesthetics and romance.

The masterpiece was Shesher Kobita – an enquiry into the nature of aesthetics and romance.

However, every character in these books was Tagore himself, with his erudition and his eloquence. This is not an inter-play of emotions but Tagore debating with Tagore, in the absence of contemporary intellects to do so. The result is a timeless tract, great literature, but not the classic novel.

But then again, what is the definition of the novel?

But then again, what is the definition of the novel? Given the wide permutation the novel has achieved post-war, and Tagore’s notoriety for being ahead of time, they can be happily accommodated today. But this still does not take away our right to view him critically.

A foolhardy, but apparently mediocre filmmaker recently attempted a narrative based on Tagore’s relationship. Faced with the ire of the Rabindrik moral police, the film did not see the light of the day. This is something Rabindranath himself would not have condoned.

Let there be irreverence. From debate reverence would arise if deserved. Respect cannot be obtained through coercion.

Visuals by Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By