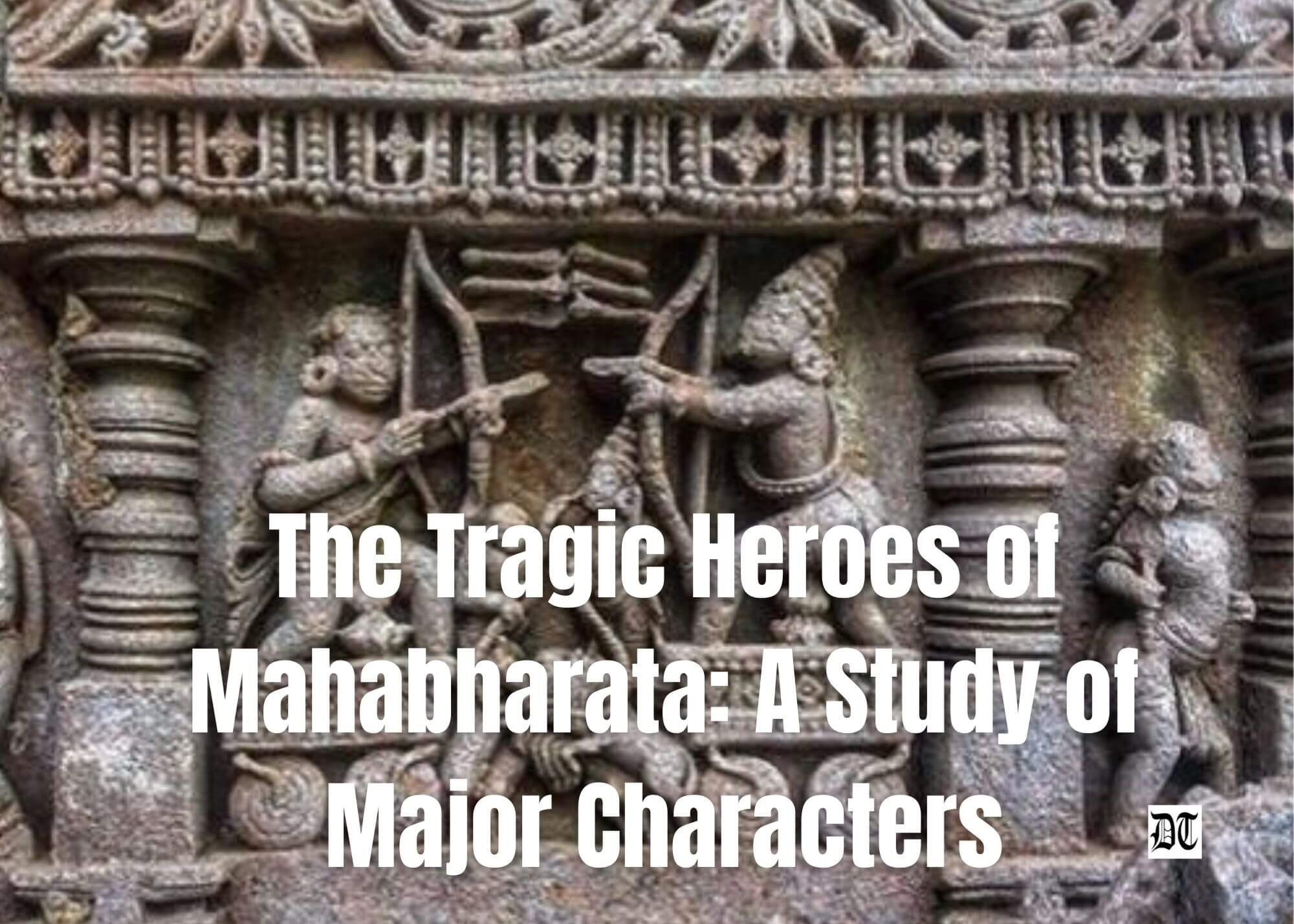

This in-depth article, by Dr. Jernail attempts to venture into a study of the main characters of Mahabharata as tragic heroes. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Mahabharata is the most admired serial on the Indian silver screen, which struck gold for the creators BR Chopra, and now the Star Plus. Originally written by Ved Vyasa, the great epic, also called the Fifth Veda, has held the breath of populations since times immemorial, when people only read it for the sheer joy of reading the Gita. But now, the joy has multiplied with the visual presentation of the great saga. The Mahabharata of BR Chopra had mass appeal, and was conceived less in making billions than in a sense of spiritual joy, as compared to the Star Plus version which is a great commercial success and appeals to modern sensibilities, with highly paid actors and actresses, whose life style has nothing to with their characters. While the content remains the same, it is the personality of the stars which has given each version of Mahabharata a sense of being different and not without a sense of satisfaction for the viewers.

Mahabharata is “the longest poem ever written” having 1,00,000 slokas or over 2,00,000 individual verse lines.

Traditionally, the authorship of the Mahabharata is attributed to Vyasa. The text of the epic reached its final form by the early Gupta period (4th century CE). Mahabharata is “the longest poem ever written” having 1,00,000 slokas or over 2,00,000 individual verse lines. With 1.8 million words in total, the Mahabharata is roughly ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined, or about four times the length of the Ramayana.1, 2. W.J. Johnson compares the importance of the Mahabharata in the context of the world civilisation to that of the Bible, the works of William Shakespeare, the works of Homer, Greek Drama, or the Quran.3

We look upon various characters only with admiration. The great Bhishma, the great Guru Dronacharya, and the great Karna. The most intriguing thing about these three figures is that even though they were fighting on the side of Kauravas, who are identified with evil, nobody has ever looked upon them as epitomes of evil as we often do with Duryodhana, Dushasana, and their kinsmen Kamsa and Ravana. Herein lies the idea of this article because it is possible to discover in them all that goes with Aristotle’s perception of the tragic hero.

According to Aristotle, a tragic hero belongs to the royal class, is essentially a good man, but has a weakness in his character…

According to Aristotle, a tragic hero belongs to the royal class, is essentially a good man, but has a weakness in his character, and then, due to an error of judgement, takes a wrong course, and finally meets his end. With his death, there is a flood of relief, and a catharsis of the feelings of pity and fear. Pity and fear are the emotions which are aroused when we see Karna dying, Bhishma on the bed of arrows, and Dronacharya relinquishing his desire to ‘be’.

Looking upon Bhishma, his own Pratigya (solemn vow), his great vow to protect Hastinapur, is still looked upon as a great resolve as he decided to remain unwed and possessed the boon ‘to die at will’. He was a great warrior and military general of the Kuru empire. His tragic flaw was his blind love for Hastinapur. His resolve was great in conception, but poor in execution. It was this vow which forced him to keep shut when he must have spoken in favour of the Pandavas. It is not that he does not speak up, he does, but it lacks will.

Tragic characters are not flat characters. They are extraordinarily complex creations.

Tragic characters are not flat characters. They are extraordinarily complex creations. What imparts him Hamletian touch is his mental and physical division within and without. One may never see a man so divided against himself. He loves the Pandavas, he is against Draupadi’s (their wife) disgrace in the royal court. He does speak, but then, he is outsmarted with Shakuni’s wit, and Duryodhana’s foul language. He turns a meek spectator to the worst spectacle in living memory. He was a good soul, but here, he had to support evil, masquerading as dharma only in name, and he knew it. This choice was his error of judgment, which led to his moral fall, and rest of his life, including the great battle he fought with Arjuna, was only a long series of self-inflicted pain, because he loved them so much, yet fought them so much, and ultimately, suggested to them, how he could be vanquished. He was a warrior who fought for an empire in such a complex manner that his support engineered its very fall. If he had stood up against Duryodhana, and the blind King Dhritarashtra, he could have stopped the great war which claimed millions of lives on both sides, including the killing of great warriors. But he didn’t. Or, better, he couldn’t. And once started, we see him helplessly drawn into a bloody battle, in which he blesses the Pandavas with Vijayshree (victory). His fall due to his error of judgment actually raises him in the eyes of the spectators, and he stands before us as a great tragic hero, even when he was killed fighting on the side of evil. After Oedipus, it is difficult to find another tragic hero among Shakespeare’s tragic heroes, who could match the enormity of the tragedy that he suffers, before he finally says: die. The moment of revelation and glory for him, at last, struck when Lord Krishna made him realise the hollowness of his Bhishma Pratigya, which was justifiable as an individual, but stood in the way of public good.

Dronacharya, the great guru, whom the Kauravas and the Pandavas held in high esteem, suffered nearly the same fate. Internally and emotionally, he too was divided against himself. The inside was divided against the outside. He was a military strategist who loved the Pandavas yet fought on the side of evil. His tragic flaw was Ashwathama, his son, whom he had ill-groomed, and who stood by Duryodhana, in the fight, and had a barbarous bringing up, lacking all-natural respect for his father’s wishes. It was Ashwathama whose insistence to stay with Duryodhana, forced Dronacharya to fight on the side of evil, always unwilling to fight and kill the Pandavas. He too was a split personality, a complex character, but a victim of his own tragic fate, because he could not cope with his own son’s partiality for evil Duryodhana. Ashwathama was his tragic flaw, and the evil trio forced him to create a Chakravyuh which claimed the life of young warrior Abhimanyu. While characters like Duryodhana and Dushasana had nothing to do with the moral situation, Dronacharya was a great loser, because it pitted him against the general good, and he emerged less as a tragic hero and more as an evil character. But, at last, he too receives the vision of reality imparted by the Lord, and the revelation makes him realise how foolish was his passion for his son, and how he was driving himself at breakneck speed into the depths of unsustainable human behavior, when he decides to relinquish his war-arms and is beheaded by Drishtamnyu. There is a flood of relief when Guru Dronacharya finally dies, ending a painful existence, due to his tragic flaw, his love for his son. One wonders if great characters like guru Dronacharya had such foolish passions even when they had grown up to great stature as a Guru.

Another character who defies denotations and towers the list of tragic heroes is Karna.

Another character who defies denotations and towers the list of tragic heroes is Karna. He is the most deprived character, ‘Sut Putra’, as he is called, and the epithet of ‘Ang Raj’ that he receives from Duryodhana is no consolation for him. He was deprived of his ‘Kavach’ [safety shield, which was a part of his body] by god Indra, because the divine forces had engineered his fall, before Arjuna. He had a passion to prove to the world that he was the best archer (dhanurdhar) in the world, and better than Arujuna. Indira, who took his safety shield, had, as a compensation, blessed him with a ‘Brahm Astra’ [a divine strike power] which he could use only once at an enemy who was in front of him. Lord Krishna, who represented divine forces, which wanted establishment of a good dispensation in Arya Varta, engineered bringing in Ghatotkach, Bhima’s son from Hidamba. He started killing the Kuru army and spitting fire. He picks up Duryodhana like a toy in his hands. At this, Duryodhana forces Karna to use his ‘Brahm Astra’ against Ghatotkach. Lord Krishna succeeds in divesting Karna of his supreme power, and he falls to the mortalising strike of an arrow from Arjuna, while trying to pull out the mud-struck wheel of his chariot.

What makes him a tragic hero is his tragic flaw of being a great Daanveer, the great giver. Indra made use of it when he asked for his safety cover. The second major issue which snapped his will to kill any of the five adversaries was the revelation that he was their eldest brother, and he gave word to his mother Kunti, that at the end of the war, her five sons will remain alive. His death in the lap of his mother Kunti brings up the essential ‘Karuna’ (pathos) of his situation. How he fought against himself. He was a truly tragic character who was divided so much against himself. He was Duryodhana’s best friend, on whose strength the latter had initiated this great war. Lord Krishna tells Duryodhana that it was Karna’s great fighting powers that were behind Duryodhana’s reckless and rash conduct with the Pandavas. In this way, Karna becomes the ultimate cause of the war, his powers are misused by Duryodhana, but no historian, however biased he may be against Karna, can club him with the evil rampant in Hastinapur. Even when he stood by Duryodhana, and declared his resolve to fight a great battle against Arjuna, he retained his grace as a gentleman, and he fought with the full knowledge that he would never win. He was great in his life, and in his death too. And, his end, though conceived in treachery, finally brings out a flood of relief. A tortured soul ends its tumultuous journey.

It is tempting to look up to Duryodhana as a strange character, cast in the western model of a Macbeth.

It is tempting to look up to Duryodhana as a strange character, cast in the western model of a Macbeth. He has a singular passion: the throne. It was so with Caesar too. But Caesar had his good points. Duryodhana lacks complexity. He never entertains any ideas inimical to his passions. Reflection is not his forte. If he does not find evil, he starts searching for it, and then holds research on it, and honours himself with a doctorate in evil. His maternal uncle Shakuni was just a foil, so was his father Dhritarashtra. His brothers were an abstraction, just like his wife and his sons, if he had any. Even as an action hero, he lacks convincing power. One wonders why sensible parents would name their son Duryodhana, which means a brave warrior gone the evil’s way. The same question sticks to Dushasana also, which means an evil administrator. Their very names, like Oedipus’s, tell the viewers that these are flat characters, evil in their conception, and evil in their execution. Still, I find one aspect of Duryodhana’s character which needs special mention.

Looking at Duryodhana as a tragic character would appear to be a crude attempt bred in extreme partiality. But as an independent observer, it is not difficult to look into his mind. He is almost like Macbeth, crude in the execution of his ambitions. Yet, there is one aspect that imparts a touch of tragedy. It is the split personalities, divided loyalties, and uncertain jerks of conduct among major warriors who fought under his command. What can be more tragic for a Crown Prince if his General does not confer on him the boon of Vijayshree? Bhishma, who fought on his side, actually fought himself, and finally died at his own behest. The other major figure on whom Duryodhana set his stock was Karna. After Karna’s death, Duryodhana comes to know that he was the eldest of the Pandavas, he never killed even one of them. Nobody in the court was on his side, and a part of his plans, except his father, who too was often divided. Guru Kripacharya and Guru Dronacharya both were against the disrobing of Draupadi in the royal court. Still, they fought on Duryodhana’s side. Balram, Lord Krishna’s brother, believed in a non-partisan relation, whereas the latter was batting all out for the Pandavas. So, in all, it was a battle, which was entirely out of proportion. From the very beginning, it was tilted towards the Pandavas. Only bodies of great warriors like Karna, Dronacharya, and Bhishma fought on Duryodhana’s side, while their sympathy, their empathy, and their blessings remained with the Pandavas. However, one could have counted Duryodhana at least half in the league of the tragic characters, but for the foul play by Shakuni, who was a tragic joker of this whole bloody spectacle.

Looking at the ideas of tragedy and comedy in the Indian context, the Indian mindset is not made for tragedy.

Looking at the ideas of tragedy and comedy in the Indian context, the Indian mindset is not made for tragedy. Indian ethos is transcendent in conception, and all great battles, fought in mythology, like the Ramayana, and even Mahabharata, ended at an affirmative note, the establishment of the good, after uprooting the evil. This belongs essentially to India’s mindset, to look for the seeds of the good even in the worst that is happening around. The fight between Rama and Ravana too had all the elements of tragedy, yet, what happens at the end is the establishment of Ram Rajya. In Mahabharata too, killings of millions of people become fodder for a happy state of affairs, establishment of a Bharat Rashtra based on goodness of human conduct. The Indian ethos is the ethos of hope, creativity, and goodness and tragedy do not have sway over the human urge to spring back to life, joy, and start it afresh. Mahabharata and Ramayana, both have their dark phases, but finally, they end with a resumption of happiness and joy. But, it is not so with Oedipus. It is not so with Dr. Faustus. And can one ever imagine a tragic hero like Macbeth, even in his last moments, coming to the realisation of his nonsensical passions? Here, I find a contrast between the eastern and the western value systems. And it contrasts the two modes of living. One is the mode of action (west) and the other is the mode of reflection (east).

References

1. Spodek, Howard. Richard Mason, The World’s History Pearson Education: 2006, New Jersey. 224,0-13-177318-6

2. Amartya Sen, The Argumentative Indian, Writings on Indian Culture, History and Identity, London: Penguin Books, 2005.

3. W.J. Johnson (1998). The Sauptikaparvan of the Mahabharata: The Massacre at Night, Oxford Univ. Press, p. ix, ISBN 978-0-19-282361-8.

Visuals by Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By

Congratulations Dr Anand for your beautiful analysis of the well known heroes of the great epic Mahabhart. Nevertheless, there are lesser known characters like Hidimbi and Ghatothkacha whose role might be considered not lesser heroic.