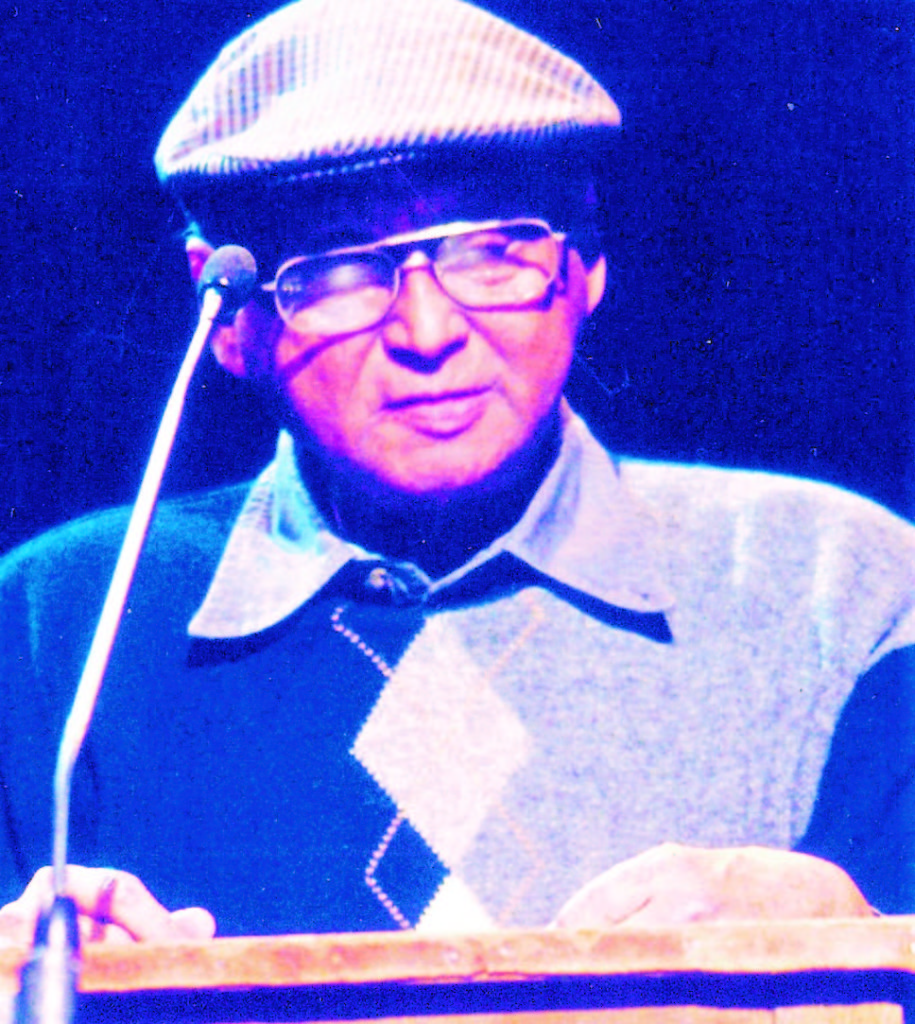

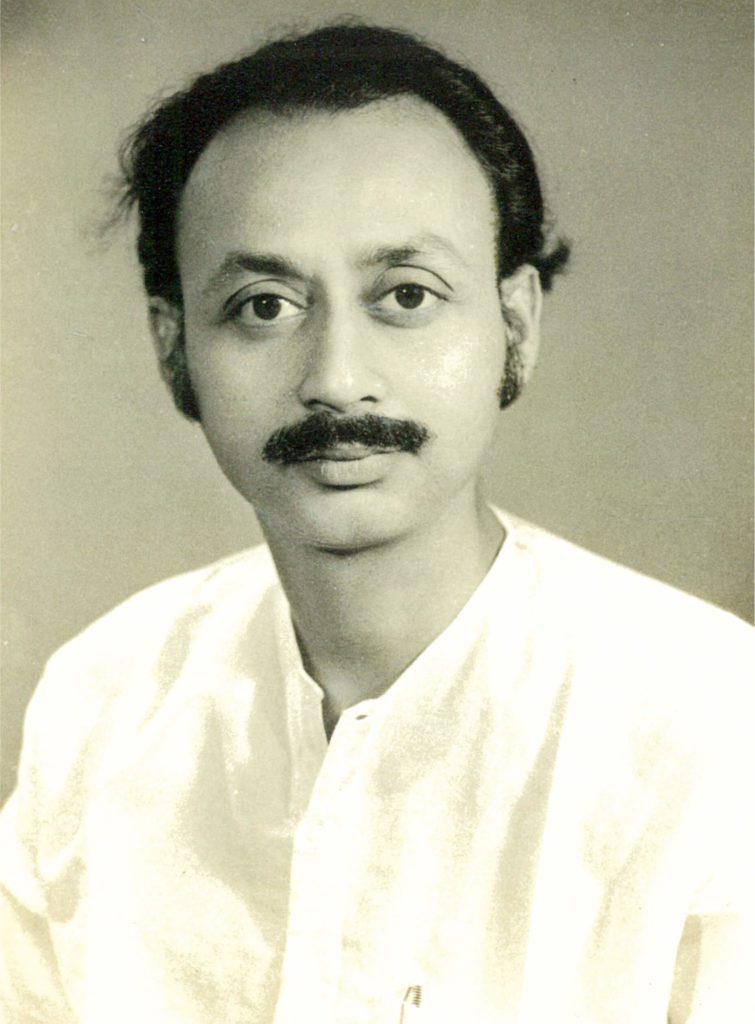

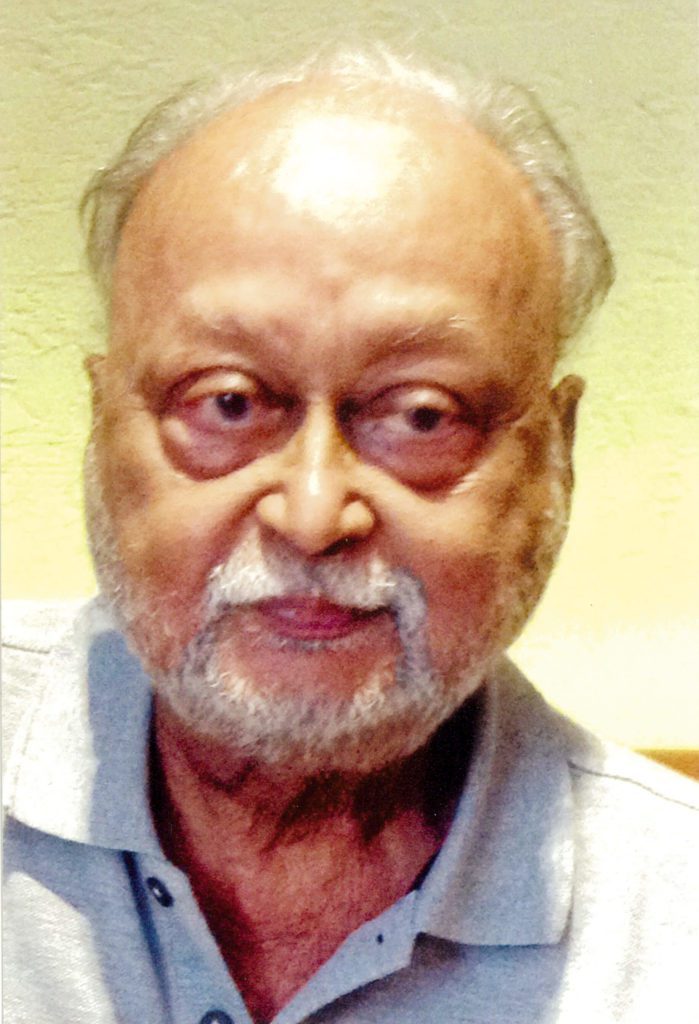

On Sunday, Jayanta Mahapatra (1928–2023), a poet and literary figure of international renown, passed away at the age of 95 while receiving medical care at SCB Medical College and Hospital in Cuttack. He had been undergoing treatment at SCBMCH for pneumonia. We offer him our tribute.

In a soul-baring rendezvous with Urna, he revealed his childhood; the launch of his journal Chandrabhaga; his relationship with poetry, life, his wife, and much more. The celebrated modern Indo-Anglican poet, in his nineties, gave an exclusive interview to Different Truths.

A small, niggling doubt has often crossed my mind. Is it best to keep our heroes at a distance? Worship the writers and poets we admire, from far, far away. Safely seated as they are, on that gilded pedestal, carefully constructed for them, in our heads and our hearts. And what happens if we interact with them on a personal level someday? See them for the human beings that they really are. Would those diamond-encrusted images splinter and crack a bit? And how do we cushion our worshippers’ expectations?

I have been a diehard fan of Jayanta Mahapatra – I endearingly call him Jayanta-da – ever since I was in class VIII. And having to interview someone who is my Poetry God, filled me with much hesitation, many a nervous twitch. But all my trepidation melted away under the resplendent, sunshiny goodness of Jayanta-da.

Someone who can teach us many lessons about humility, kindness, and what it means to be a colossally gorgeous human being. And as I interacted with Jayanta-da, the real man behind the iconic work and covetous awards, I realised he deserves every bit of the pedestal. Along with the throne, the crown, the velvet cloak, the embellished sceptre, and all that we endow our poetry heroes with.

Urna: Please tell us, your readers, and your fans about some of the earliest influences of your life. People, places, or about the sociocultural environment, so to speak. Some of the earliest influences that you think were crucial to shaping you into the doyen of Indian-English poetry, the icon that so many millions of us admire and look up to.

Jayanta: The gentle British headmaster of my school has been dead years now. Two years back I was standing by his grave in the cemetery by the river, and there was nothing in my mind; the sorrow I felt once had eased into a kind of sleep. But there he was, at the back of my mind, a man who had given away his humility, his learning, to a boy who had not understood these things.

It was from him, and the other teachers in my school, the Stewart European School, that I imbibed the love for a language that would move me so much, that it would become the utterance of my soul.

But school was an unhappy place for me. I was the youngest in class; and the poorest among them. It was my father who wanted me to have an English education, and he did that with the meagre salary of a schoolteacher in a minor school.

Taunted, bullied by my classmates almost all the years I was in school; perhaps because I was good at studies, and then because I looked like a naked little worm, I sought escape in books – books that made me dream. I loved to go into the novels of H. Rider Haggard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Walter Scott, and all my loneliness seemed to go away. But home was no different for me. With my father’s transfer into the interior of Odisha, and I being the eldest, I had to do a lot of chores, again because my mother was ill. Her attitude towards me wasn’t right, I felt. She lied about me to my father when he came back home for short visits, and our home didn’t seem like mine.

Impulsive as I was, I ran away from home, landing in Bombay, sleeping under the stars in an open bench of the Chinchpokli railway station, and with no money. It was my father’s efforts which brought me back. And another time, I spent a hot, muggy night just outside the Howrah rail station, crouched among the many passengers and some destitutes who had no place to go.

Yes, it could be my wrong notion that I clung to, that I was not understood by anyone, but I felt that way. And the days passed by, with few friends, mostly by myself, until I left for Patna University to pursue my studies in Physics. And the railway journeys which I made alone, were almost nightmares in crowded compartments, which I could enter only through the door window, pushed by a coolie – and this happened every time.

All in all, childhood for me is something I don’t want to go back to. Yes, I was unhappy. Freedom was what I craved, which seemed nowhere in sight. My Patna days were no better; most evenings spent alone by the Ganga, near a funeral ground. And those days passed by too. Days of dreams and the pain of my solitude.

But were these days to be, to remain hurts all my life? I cannot say. But each little hurt, when and if it healed, left its scar behind. That’s how I feel. I never, never imagined I would go on to write, and that too, poetry.

Fiction was what I loved. And there was so much to love in books and to learn from. I was immersed in the dreams they provided, in the language, those dreams were woven too. If I feel happy today, living alone, it is simply because books have brought me all I need.

But I have digressed from your question. Well, I did not have the influences you speak of. Nobody ever voiced before me the thrill of writing poetry; I was always thought of as a dumb teacher of physics.

Mainly a wanderer, I did photography and was happy doing it, but then turned to doing research in Theoretical Physics. I left that too. Until, late in life, I began writing poems. Perhaps everything I kept on searching for in life, in the confusion of my heart and mind, awakened, to exist in the writing of poetry.

Urna: Jayanta-da, you were the first Indian-English poet to get the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1981, and then the first Indian-English poet to be made a Fellow of the Akademi in 2019. The Sahitya Akademi Fellowship is perhaps the highest literary honour ever bestowed upon an English poet in India. Share your thoughts and feelings.

Jayanta: Yes, I felt good when the Sahitya Akademi gave me the award in 1981, but it didn’t match the thrill when I received the second prize at a worldwide poetry contest, held by the Who’s Who in Poetry, in London, in 1970. I was beginning to write then, and this award really helped me to build my confidence.

What was exceptional about the Sahitya Akademi Award was that it was the first time when it was being given for poetry written in English.

I must confess that it was an occasion for celebration; and it was, more for my wife, Runu, whom I kept neglecting in the course of my writing.

But for me, Urna, it became a burden, a sort of weight on my shoulder, and I am never free from it. And it was the same for the other awards that came in, including the latest Fellowship from the Akademi.

Wasn’t Sir Winston Churchill right when he remarked that a medal glitters, but it also casts a shadow?

Urna: In the late seventies, there were very few standard magazines for Indian poetry. One had to send one’s poems abroad for publication, and that was neither easy nor affordable, most of the time. Tell us a little about the birth of your trailblazing magazine ‘Chandrabhaga’, which became a dazzling, inclusive platform for new as well as established poets.

Jayanta: In 1979, my young friend, Dev persuaded me to start a journal, which would cater basically to poetry. Running a poetry journal in India was not an easy thing. But there was a dearth of poetry magazines, and the ones that were there did publish a lot of weak stuff. The idea excited me, but to produce a quality journal was a matter of concern.

Two points held me. One, as editor, I had to select the best that was offered to the magazine by poets all over; and secondly, to present the magazine in a format that allowed the reader to see exactly how good the poems and stories were. And Chandrabhaga was the outcome. The magazine was something I loved to do.

I felt that the serious reader would be happy with it. And, to my surprise, it did make its mark in literary circles. The material was indexed in places that matter, both in the US and India.

I felt content. Strong work kept coming in, but less of it. And the magazine did help writers starting out. A case in point that makes me proud, is that we published Amit Chaudhari’s work in 1980 when he was an unknown.

But it was difficult to keep it going. Chandrabhaga had to stop publication because we couldn’t get enough subscribers. It was also such a serious publication that few poets could find a place in.

However, my restlessness could not be curbed. In 2000, once gain, Chandrabhaga appeared in a distinctive, enviable format, and was published regularly for eight years. But although my wife had nothing to do with it, her death the same year somehow upset all schedules. I have always been foolish, impulsive, temperamental. And Chandrabhaga, once again, stopped appearing in 2008.

Two years back, I brought out the magazine again. But only one issue appears in a year, and very soon, Chandrabhaga #18 should be out. My foolishness has no end.

Urna: What life takes away from poets and artists, does it come back in some way, in their works? There are many examples, but a case in point was Tagore’s personal life, which was full of upheavals. Your comments?

Jayanta: Frankly, I wouldn’t know how to answer this. The poetry I wrote, like my own life, has always kept me on the defensive. The world outside has bruised me. The writing of a poem has been a painful act, perhaps leaving me lost and desolate. But the need for writing poetry is strong, regardless of its effect on what happens. And poem by poem, it goes on to reveal the life of the poet. And, at the same time, poetry makes the poet react in a more authentic way to life and to the world around.

My own experience isn’t something I’d like to talk about. When you are into poetry, you are into thought, taking you away from reality. You don’t notice the little things that make your day. And affections, and concerns.

Today I suffer from a strong sense of guilt because Runu was far from my thoughts through my writing years. Periods of abandonment and indifference. Maybe I forgot the existence of Runu, or it was a deliberate straying of affections, I can’t say.

But do you know, Urna, and of this I am sure, that although one’s poetry, the writing of it, creates a sort of chasm in the family; poetry by revealing the person behind the poems, binds the poet to other people. In other words, poetry presents the opportunity for him to be loved by others, making him social at the same time.

Urna: You had once said in an interview, “I fell in love with English. I played with words, turning them over and over again until they were heavy with meaning.” From physics to poetry, tell us a little about your love for words? And finally, a steaming hot cup of tea or a delicious mug of frothy coffee? What is your favourite writing companion?

Jayanta: I don’t think it was an impulsive outbreak when I said that I loved to play with words. My love for language goes back to my school days, when I would find a quiet corner with a book to escape the ragging that shamed me. I’ve been with books ever since; fascinated by the English language, I did experiment with words whenever I felt like it.

But Physics was a subject I liked and did well in, both in school and university; and my first-class master’s degree got me a lecturership. However, I spend my spare time reading, mostly fiction. And I loved to wallow in the words. This meant I was also learning at the same time. And Physics never interfered with my love for literature.

When I started writing poetry, and that too at a late age, I felt my English would be the right medium to express my emotions, and I wasn’t wrong. Higher physics and poetry said the same thing: the chaos in the universe and the ambiguity, the uncertainty in life. Physics was the poetry of the intellect, and poetry the science of human emotions. And there could be no contradictions between them.

I couldn’t give up writing poetry. My poems began appearing in leading literary periodicals abroad. And I felt good.

Today, I still write. I don’t have any specific times. I don’t need tea or coffee. All I want is the sunlight to come through my window and the tremble of the wind in the trees beyond.

***

***

Five Poems by Jayanta Mahapatra

POEM #1

I am Today

I am today. I write a poem whose words fall to pieces before the poem is made. The oriole does not call, I know I’ll never hear it again. It’s a name now in a child’s picture book. I remember the dead sparrow I picked up one early spring morning, and how it made me human as I held on to the little sorrow. Today, I am. No one quite knows my heart, It’s inside a petrified loneliness of its own. All the visible we’ve loved once: the love of frog riding frog in the rain the fruit bats swinging in the deodars and the colour of darkness that could put out the light. I am today. Walk through it, its smells of blood and paint, petrol and cement, lipstick and factory waste, and the death murmur of trees. Cry, children cry the silence of the earth as you drift down without echo the silk-stockinged sleepless city.

POEM #2

The Hour

Someone looks around for somewhere to go, when my heart flutters heavily in my chest, the sick blue tuberose can hardly beat its wings against the breeze, as old men go out to sit by themselves, assuming the manners of each other. This is where the light does not belong to those passing through, to those who do not belong in the moments where the light, unable to climb onto a poem and build itself into the art of death, lies down righteously in a patch of grass. Time and the sky roil into signs of night, the prophet with his scrambled dreams loses himself in the turns of the world, and squab pigeons fly free somewhere out there, look down, pushing through a shadow in the air into another world. (After my son’s death, March 10, 2018)

POEM #3

Sickles

Dust seems in no hurry now, sailing the air. A ten-year-old girl runs after her home-bound cows through the ingenious sunset hour, glancing briefly as we pass by but gives no sign that she has seen us. The day’s last light surprises us, leaving everyone suddenly on an endless, desolate shore. And a small desire to make love then. Women returning home from fields of ripe grain carry sickles in their tired hands. The cut paddies cling to their quiet perches. How little I understand myself, among children who are mothers before the floods come, wetting the reeds on the shore; among women desired, even as we are indifferent to happenings by which they are possessed. How the sickles shimmer with the reds of sunset hidden in the twilight of their veins.

POEM #4

A Still Winter Morning

A still winter morning, and a sullen mist playing with the pallor between its fingers. The only door to an exhausted village hut opens noiselessly like a tongue hung out. Just the shadow of a woman comes and goes through it into the little vacant yard. In a corner the scanty, harvested paddy is wet with dew. Guavas glow green everywhere with adolescence. From far down her body, grief, death and widowhood peer at the woman’s old father, like a lost sheep huddled away from death. The odor of rats sticks to the sagging floor. Hunger looks from the middle of a breath. Once again, it has nowhere to go. On this still winter morning. What light there was, has not entered her eyes. Just a woman’s shadow up against a wall of that home of hers so inviolate it has never opened inside her.

POEM #5

A Missing Person

In the darkened room a woman cannot find her reflection in the mirror waiting as usual at the edge of sleep In her hands she holds the oil lamp whose drunken yellow flames know where her lonely body hides.

Photos from the poet sourced by the interviewer and visuals by Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By

Truth as it should be told

Informal and Insightful interview with the great poet.

Never knew till I read the poems by Jayant Mahapatra shared by you that poetry can be such a painful act. This is poetry at its acutest. Shakes you to your core. Thanks for a most valuable interview with Da.

Acknowledge your appreciation. Thanks.

Many thanks for your kind words. All writings, particularly poetry, makes the writer/poet vulnerable.

Dear Urna, your questions are so intelligently and sensitively formatted. The answers of Jayanta Mahapatra expresses his greatness and transparency. Loved how he said, “Perhaps everything I kept searching in life, in the confusion of my heart and mind, awakened to exist in the writing of poetry”.