For healthy individuals, evidence suggests that the demand for prevention is affected by the real or perceived risk of infection, suggests Navodita, analysing the economics of infectious diseases. An exclusive for Different Truths.

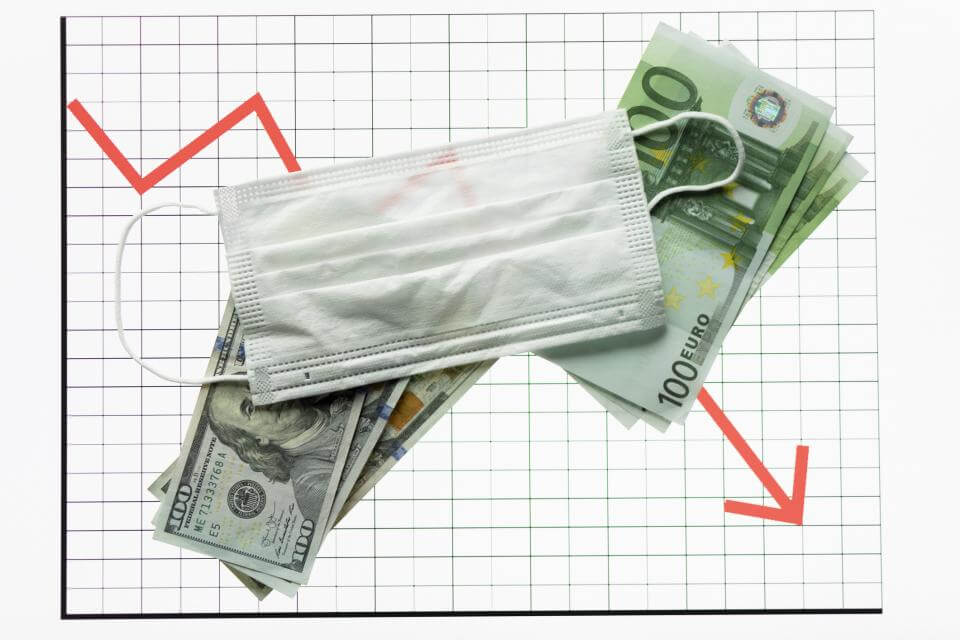

In the wake of Corona economics can make immensely valuable contributions to our understanding of infectious disease transmission and the design of effective policy responses. The one unique characteristic of infectious diseases makes it also particularly complicated to analyse: the fact that it is transmitted from person to person. It explains why individuals’ behaviour and externalities are a central topic for the economics of infectious diseases. Many public health interventions are built on the assumption that individuals are altruistic and consider the benefits and costs of their actions to others. This would imply that even infected individuals demand prevention, which stands in conflict with the economic theory of rational behaviour. Empirical evidence is conflicting for infected individuals. For healthy individuals, evidence suggests that the demand for prevention is affected by the real or perceived risk of infection.

In the wake of Corona economics can make immensely valuable contributions to our understanding of infectious disease transmission and the design of effective policy responses. The one unique characteristic of infectious diseases makes it also particularly complicated to analyse: the fact that it is transmitted from person to person. It explains why individuals’ behaviour and externalities are a central topic for the economics of infectious diseases. Many public health interventions are built on the assumption that individuals are altruistic and consider the benefits and costs of their actions to others. This would imply that even infected individuals demand prevention, which stands in conflict with the economic theory of rational behaviour. Empirical evidence is conflicting for infected individuals. For healthy individuals, evidence suggests that the demand for prevention is affected by the real or perceived risk of infection.

The one unique characteristic of infectious diseases makes it also particularly complicated to analyse: the fact that it is transmitted from person to person. It explains why individuals’ behaviour and externalities are a central topic for the economics of infectious diseases.

However, studies are plagued by underreporting of preventive behaviour and non-random selection into testing. Some empirical studies have shown that the impact of prevention interventions could be far greater than one case prevented, resulting in significant externalities. Therefore, economic evaluations need to build on dynamic transmission models in order to correctly estimate these externalities. Future research needs are significant. Economic research needs to improve our understanding of the role of human behaviour in disease transmission; support the better integration of economic and epidemiological modelling, evaluation of large-scale public health interventions with quasi-experimental methods, design of optimal subsidies for tackling the global threat of antimicrobial resistance, refocusing the research agenda toward underresearched diseases; and most importantly to assure that progress translates into saved lives on the ground by advising on effective health system strengthening.

To an economist, all individuals make active choices about preventing infection. They may get vaccinated (flu, measles, yellow fever), avoid being in confined spaces with others (TB), install sanitation (diarrhoea), wear protective clothing (Ebola), boil drinking water (cholera), use mosquito repellent (dengue), or sleep under insecticide-treated bednets (malaria). In making those preventive choices, individuals trade off the costs of prevention against the benefits of not getting the disease in future. Costs and benefits can be both monetary and non-monetary, and if they occur in the future, individuals discount them to the present day. Discount rates vary across individuals with different time preferences, and they can be time-inconsistent (e.g., a trade-off made between days 1 and 2 is different from one made between days 30 and 31). In order to predict the benefit of prevention, individuals must estimate the expected cost of disease and their personal risk of getting sick. Because the risk of getting infected is uncertain in most situations, the prevention decisions are affected by individuals’ risk preferences, with risk-averse individuals more likely to demand prevention. The trade-offs underlying preventive choices are not generic to infectious diseases. What is unique in comparison to non-communicable diseases is the fact that the risk of getting a disease is directly related to how many other individuals have the disease and that the preventive choice made by one individual impacts on the risk of others getting the disease.

What is unique in comparison to non-communicable diseases is the fact that the risk of getting a disease is directly related to how many other individuals have the disease and that the preventive choice made by one individual impacts on the risk of others getting the disease.

Many other factors affect the demand for prevention, most of which are not generic to infectious disease. In a review, poor delivery of preventive services, lack of information, or more subtly wrong information provided to the wrong target groups, lack of education, social learning or peer effects, and present bias or competing for mortality risks whereby people who expect to die young from other conditions have weak incentives for prevention. Related to this point, the availability of effective treatment reduces the demand for prevention because it lowers the expected costs of being sick.

Many public health interventions are based on the assumption that individuals are altruistic. For example, interventions that aim to improve coverage and uptake of HIV testing are at least in part motivated by the assumption that upon learning one’s status, infective individuals will make efforts to prevent transmission of the disease to susceptible individuals. The infective individuals bear the costs of their behaviour, but the benefits are enjoyed by somebody else. Classical economic utility theory considers such altruistic behaviour as irrational. The standard assumption is that individuals do not consider in their utility function the benefits of their preventive choices to others, giving rise to negative externalities. This explains why prevention is low if its provision is left to private markets. Although susceptible individuals will demand prevention even if they are not altruistic, they only consider their private benefits and not the social benefit, which is higher.

It is difficult to estimate the difference between private and social benefit because it is highly dependent on the characteristics of the disease and the intervention. This is probably why the issue of altruism among susceptibles is rarely analysed in economic studies.

It is difficult to estimate the difference between private and social benefit because it is highly dependent on the characteristics of the disease and the intervention. This is probably why the issue of altruism among susceptibles is rarely analysed in economic studies. Most empirical studies on altruism among susceptibles have analyzed vaccination decisions against seasonal and pandemic influenza among healthcare professionals. When healthcare professionals lacked the belief that getting vaccinated protects patients or relatives, the perceived risk for others due to the disease was low, or when the perceived risk of transmission was low, vaccine uptake was low. Pregnant mothers were found to be altruistic toward their unborn child. However, there was no evidence of altruism among the elderly, chronically ill patients, or parents of children under 5 years of age.

An important question is whether a country should push for and support international efforts to achieve global eradication, aim for elimination within its borders, or attempt optimal control, which involves moving into and sustaining a steady-state with a positive level of infection. It is very difficult to identify the welfare-maximising policy, and recommendations need to rely on projections of uncertain benefits far into the future. If a disease is already controlled at a very high level, for example by vaccination, then a steady state with a positive level of infections is maintained at comparably high costs, and just a slight increase in the vaccination rate would cause the disease to be eliminated or eradicated. Eradication would increase costs in the short run, and the marginal costs of the last prevented case are probably very high. If public vaccination policy is (partially) crowded out by market behaviour under the assumption that the private demand for vaccination is prevalence-elastic, then economic theory suggests that eradication may only be achievable as time goes to infinity.

Hence, concerted efforts to fight Corona alone can help all countries in the long run.

Photo from the Internet

By

By