What Sojourner Truth may have been most famous for, not unlike the firebrand anarchist Emma Goldman, was her public speaking. Illiterate throughout her life, she nevertheless had a remarkable gift for language, and from 1840s onwards, went on several speaking tours with both women’s rights groups and abolitionists. In 1850, she also began speaking on woman suffrage. Her most famous speech, “Ain’t I a woman?” was entirely improvised. Truth’s short, simple speech was a powerful rebuke to many anti-feminist arguments of the day. It became and continues to serve as a classic expression of women’s rights. Truth became, and still is today, a symbol of strong woman. Her speech was feminism’s first speech regarding intersectionality, opines Dr. Ranjana, profiling the powerful Black woman. A Different Truths exclusive.

When Sojourner Truth walked into the predominantly White Women’s Right Convention, in Akron, Ohio, in 1851, three years after the first Women’s Right Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, jaws dropped. Not a sound could be heard. At the Convention, at which Truth had agreed not to speak in order to avoid making harmful associations between the “Negro” cause and the cause of women, it happened that several men were shouting down the beleaguered women speakers. “Women expect right? They ask us to help them down from carriage and over puddles! Women cannot do even manual labour!”

“Look at my arm! I have ploughed, and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me – and ain’t l a woman?” ~ Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth couldn’t hold it anymore. She marched up onto the platform and launched into an impassioned counterattack: “Nobody ever helped me into carriage, or even mud puddles, or gave me any best place – and ain’t l a woman? Look at my arm! I have ploughed, and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me – and ain’t l a woman? I could work and eat as much as a man (when l could get it) and bear the lash as well – and ain’t l a woman? I have born thirteen children and seen ’em most sold off into slavery, and when l cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard – and ain’t l a woman?”

Truth then pointed a bony finger at a nearby preacher and demanded, “Where did your Christ come from…From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with him.” The crowd erupted in cheers. The White feminists, who had objected to her speaking, felt guilty. With this statement Sojourner demanded that white feminists broaden their vision to include the suffering and strength of Black, enslaved, and poor women in the category of women and in the fight for equal rights. Truth was an imposing woman blessed with a powerful voice and driven by deep religious conviction. She spoke English with a Dutch accent; she bore the scars of brutal beatings, the sale of her children, and the loss of her own parents while she was sold off into slavery. Surrounded by affluent, educated white women and their gentlemen supporters, her presence eventually gave rise to awe. The white women at the conference didn’t want to muddy their struggle and demands for women’s rights with the uncomfortable subject of race and the rights of coloured folk, despite their debt to Frederick Douglass’ efforts to keep the controversial issue of women’s suffrage central at the first Convention in Seneca Falls. Yet, when Truth rose to enter into the conversation, her words presaged what would come to be fundamental question of Western feminism: what exactly is a woman?

Sojourner Truth’s short, simple speech was a powerful rebuke to many antifeminist arguments of the day. It became and continues to serve as a classic expression of women’s rights.

What Truth may have been most famous for, not unlike the firebrand anarchist Emma Goldman, was her public speaking. Illiterate throughout her life, she nevertheless had a remarkable gift for language, and from 1840s onwards, went on several speaking tours with both women’s rights groups and abolitionists. In 1850, she also began speaking on woman suffrage. Her most famous speech, “Ain’t I a  woman?” was entirely improvised. Sojourner Truth’s short, simple speech was a powerful rebuke to many antifeminist arguments of the day. It became and continues to serve as a classic expression of women’s rights. Truth became, and still is today, a symbol of strong woman. Her speech was feminism’s first speech regarding intersectionality. What she means by “Ain’t I a woman?” is that sure, she may be Black, but that’s not the only thing that defines her. She is a woman too, and she’s a mother and a former slave as well. This is what intersectionality is: A theory about the ways all people’s experiences of life are created by the intersection or coming together of multiple identities. Intersectionality “describes the simultaneous, multiple, overlapping and contradictory systems of power that shape our lives and political options.” While this theory can be applied to all people, and more particularly all women, it is specially mentioned and studied within the realms if Black feminism. Patricia Hill Collins, a leader in sociology and Black feminism argues that Black women in particular have a unique perspective on the oppression of the world as unlike white women; they face both racial and gender oppression simultaneously, among other factors.

woman?” was entirely improvised. Sojourner Truth’s short, simple speech was a powerful rebuke to many antifeminist arguments of the day. It became and continues to serve as a classic expression of women’s rights. Truth became, and still is today, a symbol of strong woman. Her speech was feminism’s first speech regarding intersectionality. What she means by “Ain’t I a woman?” is that sure, she may be Black, but that’s not the only thing that defines her. She is a woman too, and she’s a mother and a former slave as well. This is what intersectionality is: A theory about the ways all people’s experiences of life are created by the intersection or coming together of multiple identities. Intersectionality “describes the simultaneous, multiple, overlapping and contradictory systems of power that shape our lives and political options.” While this theory can be applied to all people, and more particularly all women, it is specially mentioned and studied within the realms if Black feminism. Patricia Hill Collins, a leader in sociology and Black feminism argues that Black women in particular have a unique perspective on the oppression of the world as unlike white women; they face both racial and gender oppression simultaneously, among other factors.

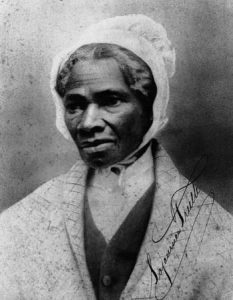

The woman as we know as Sojourner Truth, was born of slave parents owned by a wealthy Dutch patron in Ulster County, New York as Isabella Baumfree. She is remembered for her unschooled but remarkable voice raised in support of abolitionism, the freedom and women’s rights. She was sold several times. In 1843, she took the name Sojourner Truth, believing this to be on the instructions of the Holy Spirit and became a travelling preacher. She was born a slave but she was freed in 1827, when the state abolished slavery. Lack of education did not stop her from travelling to speak to people about God and his hatred to unfair treatment of African and women. She had such a full experience of the wrongs of slavery that she could not believe they were permitted by God. She was sure He must hate them, and would destroy those who persisted in perpetuating them. As for the feminist part of her teachings, she often asked the question: “Was not Christ born if woman?” She answered her own question in her famous speech in Akron, Ohio, saying, “Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part?” If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up again! And now they are asking to do it, the man better let them.”

Truth was the only voice for Black women, and for recognising the link between racism and sexism.

Sojourner Truth not only was an advocate for the rights of the African-Americans, but also stood up for women’s equality. With this statement Truth demanded that white feminists broaden their vision to include the suffering and strength of Black, enslaved and poor women in the category of women and in the fight for equal rights. With the passage, in 1867, of the Fourteenth Amendment giving Black men to vote, white suffragettes were outraged at the lack of reference to women, and most Black activists believed that the suffering of Black make slaves entitled them to receive the vote first. Again, Truth was the only voice for Black women, and for recognising the link between racism and sexism. “There is a great deal of stir about coloured women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. So l am keeping the things going while things are stirring, because if we wait till it is still, it will take a great while to get it going again.” Moving to Washington, D C. in 1863, Sujourner Truth worked on behalf of Black Civil War soldier, nursed and taught domestic skills to freed slaves and visited President Lincoln.

Truth’s “Ain’t l a woman?” speech vividly contrasts the character of oppression faced by white and Black women. While white middle-class women have traditionally been treated as delicate and overly emotional – destined to subordinate themselves to white men – Black women have been denigrated and subject to the racist abuse that is a fundamental element in US society. Since the time of slavery, Black women have eloquently described the multiple oppressions of race, class and gender – referring to this concept as “interlocking oppressions”, “simultaneous oppressions”, “double jeopardy”, etc.

“If women are allegedly passive and fragile, then why are Black women treated as ‘mule’ and assigned heavy cleaning chores…” ~ Black feminist Patricia Hill Collins

In Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Political Empowerment, published in 1990, Black feminist Patricia Hill Collins extends and updates the social contradictions raised by Sojourner Truth: “If women are allegedly passive and fragile, then why are Black women treated as ‘mule’ and assigned heavy cleaning chores? If good mothers are supposed to stay at home with their children, then why are US Black women on public assistance forced to find jobs and leave their children in day care? If women’s highest calling is to become mothers, then why are Black teen mothers pressured to use Norplant and Depo Provera? In the absence of a viable Black that investigates how intersecting oppressions of race, gender, and class foster these contradictions, the angle of vision created by being deemed devalued workers and failed mothers could easily be turned inward, leading to internalised oppression. But the legacy of struggle among US Black women suggests that a collectively shared Black women’s oppositional knowledge has long existed. This collective wisdom, in turn, has spurred US Black women to generate a more socialised knowledge namely Black feminist thought as critical social theory.

In Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Political Empowerment, published in 1990, Black feminist Patricia Hill Collins extends and updates the social contradictions raised by Sojourner Truth: “If women are allegedly passive and fragile, then why are Black women treated as ‘mule’ and assigned heavy cleaning chores? If good mothers are supposed to stay at home with their children, then why are US Black women on public assistance forced to find jobs and leave their children in day care? If women’s highest calling is to become mothers, then why are Black teen mothers pressured to use Norplant and Depo Provera? In the absence of a viable Black that investigates how intersecting oppressions of race, gender, and class foster these contradictions, the angle of vision created by being deemed devalued workers and failed mothers could easily be turned inward, leading to internalised oppression. But the legacy of struggle among US Black women suggests that a collectively shared Black women’s oppositional knowledge has long existed. This collective wisdom, in turn, has spurred US Black women to generate a more socialised knowledge namely Black feminist thought as critical social theory.

Almost one hundred years later, Truth’s questioning can be heard in Simon de Beauvoir’s challenge to claims that the meaning of womanhood is self-evident.

Almost one hundred years later, Truth’s questioning can be heard in Simon de Beauvoir’s challenge to claims that the meaning of womanhood is self-evident. In her ground-breaking and canonical work, The Second Sex (1949, 1st English Trans, 1953), Beauvoir set the course for the study of the “Woman question” in the West by putting the issue of gender into focus. Responding to male discontentment that French women were losing their femininity and were not as “womanly” as they believed Russian women to be. Beauvoir wondered if one is born or whether, in fact, one must become woman through various socialisation and indoctrination processes. This critical perspective led her to challenge the usefulness of the category of woman altogether and to ask whether it was, in fact, helpful as a term representing all the experiences of the so-called member of “Second Sex”. Perhaps nothing better illustrates Beauvoir’s concerns regarding the legitimacy and effectiveness of the category of “woman” than the development of white, US mainstream feminist thought in relation to challenges posed by woman of colour, poor, immigrants and women from “Third World nations”.

The phrase, “Ain’t I a woman?” was first introduced into North American and British feminist lexicon by an enslaved woman. It is worth learning in mind that the first woman’s anti-slavery society was formed, in 1832, by Black women in Salem, Massachusetts in the USA. Yet Black women were conspicuous by their absence at the Seneca Falls Anti-Slavery Convention of 1948, where the mainly middle-class white delegates debated the motion for women’s suffrage. Several questions arise when we reflect on Black women’s absence at the Convention. What, for instance, are the implications of an event which occludes the Black female subject from the political imaginary of a feminism designed to campaign for the abolition of slavery?

Biographers of Black women such as Sojourner Truth reveal that many of them spoke loud and clear. They could not be caged by the violence of slavery even as they were violently marked by it. Truth’s oft-quoted speech of 1851 very well demonstrates the historical power of a political subject. She campaigned for both the abolition of slavery and for equal rights of women. The words of Sojourner Truth had an enormous impact at the Convention and that the challenge they expressed foreshadowed campaigns by Black feminists more than a century later.

Photos from the Internet

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

What a remarkable journey of a beacon of strength, courage and substance.

Regards

The question raised by Sojourner Truth gave a new turn to, what we call, feminisms. The question is not only a call for self awareness to the women but a big challenge to the dominantly prevalent patriarchal hegemony. A good piece of writing by Dr. Ranjana ji