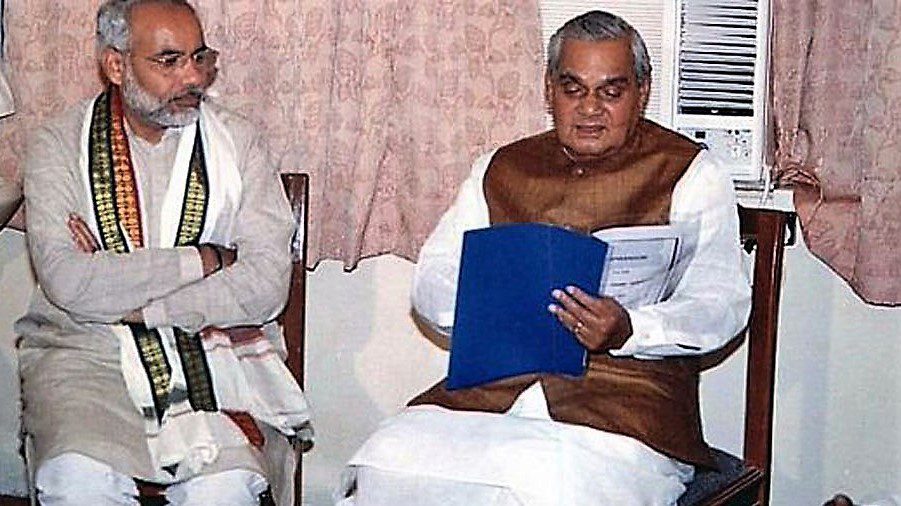

Behind the current proximity between the party and its mentor is the attitudinal difference between Vajpayee and Modi. Unlike Vajpayee, Modi has always belonged to his party’s more hawkish sections, a reputation which was highlighted by the Gujarat riots when Vajpayee had counselled the then chief minister of the state to adhere to the raj dharma of rulers of being fair to everyone irrespective of caste or creed. An analysis for Different Truths.

History will see Atal Behari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi in completely different lights for being almost diametrically opposite to one another.

The differences between the two BJP prime ministers related mainly to their temperament and outlook, which, in turn, guided their approach to governance where it concerned coalitional politics.

There is little doubt that Vajpayee established a record of sorts by running a mammoth coalition comprising 24 parties, which had never been accomplished before and is unlikely to be achieved by any of his successors in the future.

This remarkable exercise in togetherness between parties, which had little in common in terms of ideology could last for more than three years from 1999 to 2002 because of Vajpayee’s Nehruvian breadth of vision, who instinctively appreciated the multifaceted “idea” of India notwithstanding his saffron lineage.

It may be recalled that Vajpayee had described India’s first prime minister as Bharat Mata’s “favourite prince” and Nehru, too, saw in the young Jan Sangh M.P. as one of his successors.

It will not be out of place to say that in the “new” India of today, Nehru is routinely excoriated by those in the corridors of power at the centre.

It is not surprising that Vajpayee’s coalition began to fall apart in the wake of the 2002 Gujarat riots when, among others, Farooq Abdullah and Ramvilas Paswan, walked out. Two years later, when the BJP lost the general election and the Congress came from nowhere to score a surprise victory, Vajpayee blamed the riots for the BJP’s defeat.

After all, he had laid the foundation for the alliance when in the aftermath of his inability to form a government after trying for 13 days in 1998, he said that the BJP would shelve the three key points on its Hindutva agenda – the building of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, the introduction of a uniform civil code and the scrapping of Article 370 of the Constitution conferring special status on Kashmir.

The moderation which he displayed in this act of taking a step backwards, tactical though it may have been, is worthy of emulation by any party which seeks to scale the height of power.

In the context of Vajpayee’s success in forging a mahagathbandhan (grand alliance), it is not surprising that doubts are being expressed today as to whether the BJP will be able to form a coalition in case the party falls short of a majority in the next general election.

The reason for the doubts is Modi’s seemingly temperamental aversion to carry along others in a coalition, which has led to the Telugu Desam’s departure from the present government, the Shiv Sena’s constant carping against both Modi and the BJP and the Akali Dal’s patent uneasiness on the grounds of being neglected.

Even if Vajpayee’s quality of gentleness made his critics like Sadhvi Rithambara describe him as “half a Congressman” and other less trenchant say that he was the right man in the wrong party, the former prime minister always remained true to his beliefs even if this made his detractors in the RSS like K.S. Sudarshan call for his ouster.

If the RSS today is far more favourably disposed towards Modi, the reason obviously is that there is now a meeting of minds between the BJP and the RSS, which wasn’t there in Vajpayee’s time.

Behind the current proximity between the party and its mentor is the attitudinal difference between Vajpayee and Modi. Unlike Vajpayee, Modi has always belonged to his party’s more hawkish sections, a reputation which was highlighted by the Gujarat riots when Vajpayee had counselled the then chief minister of the state to adhere to the raj dharma of rulers of being fair to everyone irrespective of caste or creed.

Vajpayee is believed to have even considered calling for Modi’s dismissal till he was dissuaded by other BJP hardliners, which included L.K. Advani.

But it is the tenets of raj dharma, which have again come to the fore at a time when the minorities are feeling insecure, as a former vice-president Hamid Ansari has said, and “mobocracy” is evident as never before, persuading the Supreme Court to intervene and the government to consider enacting a special law against lynching.

In contrast to such near-anarchic conditions, as a petitioner in the Supreme Court has said in the context of the violence involving the gau rakshaks and kanwariyas, Vajpayee’s period in power appears in retrospect to be an oasis of peace except for the Gujarat riots.

Even in the matter of economic reforms, which is supposed to be Modi’s forte, Vajpayee’s initiatives relating to the “strategic sale” of a number of PSUs including Modern Foods, Balco and Hindustan Zinc, were more noteworthy than at present when the government is unable to find buyers for Air India.

From all possible angles, therefore, whether moderation or accessibility which marked Vajpayee out as a thorough gentleman, he leaves behind a legacy which will not be easy to match, especially by those whose conduct is characterised by arrogance.

Amulya Ganguli

©IPA Service

Photo from the Internet

By

By

By

By