The steps our country has made toward justice and equality since King’s death have been partial victories, born of mass collective struggles of the African-American, women’s, labour, immigrant, LGBTQ, disability rights, and other democratic movements. They are neither forgotten nor finished. Here’s a report, for Different Truths.

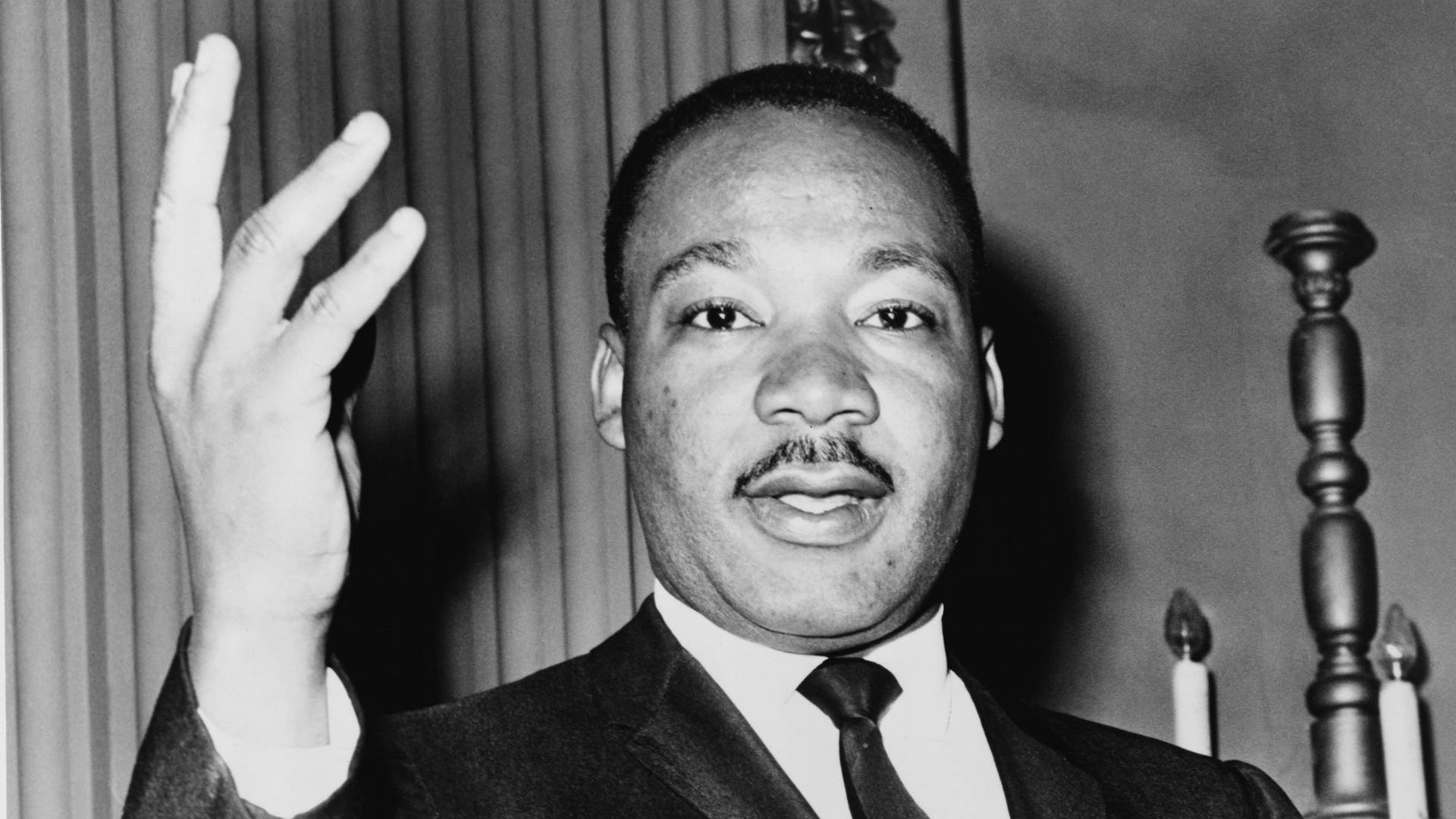

Five decades have passed since the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. In that city this week, thousands gathered to commemorate the civil rights icon’s life. From symposia hosted by the National Civil Rights Museum to rallies under the auspices of the new Poor People’s Campaign, Memphis was filled with activities marking the King legacy.

The Mountaintop Conference, organised by AFSCME, the union that represented the striking sanitation workers King was in Memphis to support in 1968, is giving special attention to the synthesis of the class struggle and the fight for racial justice that was the centerpiece of King’s work in his later years.

The conference is reminding workers and activists that, as King said, the needs of African Americans are “identical with labor’s needs—decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children, and respect in the community.”

While we look to Memphis this week and remember the greatest mass democratic leader in our nation’s history, we must also keep our attention on places such as Sacramento. There, activists are forcing the country to again confront the continued rush to lethal force by police officers during their encounters with (often unarmed) Black men.

The case of 22-year-old Stephon Clark, gunned down by Sacramento police in his grandmother’s backyard on March 18, proves once more that the United States has a long way to go when it comes to achieving equality before the law—let alone actual, lived equality.

The autopsy commissioned by Clark’s family concluded that he was hit by eight bullets—six in the back, one in the neck, and one in the thigh — and took between three and 10 minutes to die, undermining the Sacramento Police Department’s claim that he was facing officers when they opened fire. Already the contention that Clark was holding a gun has been jettisoned by the department, which now admits he had nothing more than a cell phone in his hand at the time he was killed. Whether Clark might have survived had officers immediately provided medical aid after shooting him rather than waiting five minutes will perhaps never be known.

The killing of Stephon Clark was followed by the announcement in Louisiana last week that no charges would be filed against the Baton Rouge officers who shot Alton Sterling in 2016. It showed that the eagerness of too many cops to pull the trigger is matched by the reluctance of too many prosecutors to pursue justice for those murdered by police. Coming back-to-back just before the King assassination anniversary, it can sometimes feel as though America hasn’t moved much in fifty years.

The injustices extend far beyond police violence, however. From restrictions on voting rights to a new census policy that threatens to erase millions, and from our under-funded and segregated education system to the continued school-to-prison pipeline, there is plenty to cause despair.

But resignation was never part of the King strategy; the only constant struggle was. “A final victory is an accumulation of many short-term encounters,” he wrote. “To lightly dismiss a success because it does not usher in a complete order of justice is to fail to comprehend the process of full victory. It underestimates the value of confrontation and dissolves the confidence born of partial victory by which new efforts are powered.”

The steps our country has made toward justice and equality since King’s death have been partial victories, born of mass collective struggles of the African-American, women’s, labor, immigrant, LGBTQ, disability rights, and other democratic movements. They are neither forgotten nor finished.

Mike Cody, a lawyer who worked with the Reverend in his final campaign, said a few days ago that if King were alive today, “he’d be in people’s face” about issues relating to race, poverty, and inequality.

King would probably also “be in people’s face” with the truth that he came to realize while in seminary in 1952—the fact that “capitalism has seen its best days.” No social institution can survive, he wrote in his notes, when it has outlived its usefulness. “This,” he said, “Capitalism has done.”

If Dr. King were with us now, he’d be marching—in Memphis, in Sacramento, in Baton Rouge, in Washington, and beyond. He would also be telling us all to march to the ballot box in November and make another step toward justice. Many have tried to tame the radicalism of Martin Luther King, Jr. over the past fifty years; rekindling his legacy today means joining the fight for a radically different future.

John Wojcik

The writer is the Editor-in-Chief on People’s World

©IPA Service

Photo from the Internet

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By