Tapati talks of navigation now and in the ancient time, telling us about Matsya Yantra, in India, much before the compass that we know now. Here’s an erudite research, in the regular column, exclusively in Different Truths.

As I was idling in my balcony, enjoying the cool breeze of early winter, gazing at the evening sky was a treat to the eyes. The setting sun put a blazing palette unravelling nameless hues; the cotton balls of clouds were soon changing their shapes emerging into newer imageries; the golden layers soon became orange and a blazing red before immersing into dusk when in the dark slate stars appeared like the last glitters of a great firework. In a splash of falling eyelashes, twinkles peeped and splattered and flooded all over the sky. The skyline became a canopy of lighting, a reflection of the past festival of lighting. I stood lost counting the new stars and started recalling the names of the glowing planets above my head; it was an unmindful walk from my childhood memories when we stood among a group of children with eyes fixed on the sky and small fingers pointing at the stars with their names.

The Polestar was the blue diamond on the early setting of dusk and dawn after travelling across the sky; we were told how mariners would decide the directions with a look at it. When we grew up, we tried to locate the direction with the compass and reaffirm the Polestar in a playful mood. A sudden feeling of horror shivered down with a thought of getting lost in the vast universe without any knowledge of direction. Wild imagination drew me being lost in the darkness of a seamless desert or an endless ocean of water and sighting the polestar was such a solace of being not getting lost but showing a direction.

The Polestar was the blue diamond on the early setting of dusk and dawn after travelling across the sky; we were told how mariners would decide the directions with a look at it. When we grew up, we tried to locate the direction with the compass and reaffirm the Polestar in a playful mood. A sudden feeling of horror shivered down with a thought of getting lost in the vast universe without any knowledge of direction. Wild imagination drew me being lost in the darkness of a seamless desert or an endless ocean of water and sighting the polestar was such a solace of being not getting lost but showing a direction.

Today, explorers and adventurers never forget to sight the polestar even while having the modern equipment, a navigator’s compass in their hand. Who discovered the compass I really do not know and started digging into it. Google informed among the Four Great Inventions, the magnetic compass was first invented during the Chinese Han dynasty around 300 and 200 BC. Prior to that geographical positions and directions were determined by sighting celestial bodies and their positions or astronomy. But when the sky was overcast or foggy to cover the sightings, men discovered compass to enable mariners to have a safer journey. Loadstone was discovered and cardinal directions were fixed with its help.

A magnetic compass with needle has been described by Kanad (around 550 BC)

to signify that the iron needle would go towards the magnet.

Milindapanho composed during 4th-5th centuries CE, mentions about an instrument used by the pilot of a ship for steering the ship:

“And again, O King, as the pilot put a seal on the steering apparatus, lest anyone should touch it”. It has been translated as a ‘steering apparatus’ and it Sanskrit it is‘ yantra’, a mechanical devise, just like ‘Matsya yantra’ working on mechanical and accompanied with other principles.

“Historians point out a compass on one of the ships in which Indians of early Christian era sailed out to  colonise islands in the Indian Ocean. The Hindu compass was an iron fish (called in Sanskrit Matsya-yantra or fish machine). It floated in a vessel of oil and pointed to the North.

colonise islands in the Indian Ocean. The Hindu compass was an iron fish (called in Sanskrit Matsya-yantra or fish machine). It floated in a vessel of oil and pointed to the North.

“The early Hindu astrologers are said to have used the magnet, in fixing the North and East, in laying foundations, and other religious ceremonies. The fact of this older Hindu compass seems placed beyond doubt by the Sanskrit word Maccha Yantra, or fish machine, which was named as the mariner’s compass.”

Indians thus had already in use a magnetic compass known as Matsya Yantra for determining direction. The work, Merchants Treasure, written at Cairo by Baylak al Kiljaki mentions the magnetic needle as being in use in the Indian Ocean.

When Columbus took his voyage and all mariners had at that time, was an astrolabe or cross-staff, a rudimentary compass, and inaccurate nautical charts. There was also a basic understanding of how to get approximate latitude by taking an altitude of Polaris, the Polestar. But navigation was dangerous and inaccurate. Columbus’ journal confirms that he could not calculate even latitude properly. Small wonder that he landed up in the Americas looking for India!

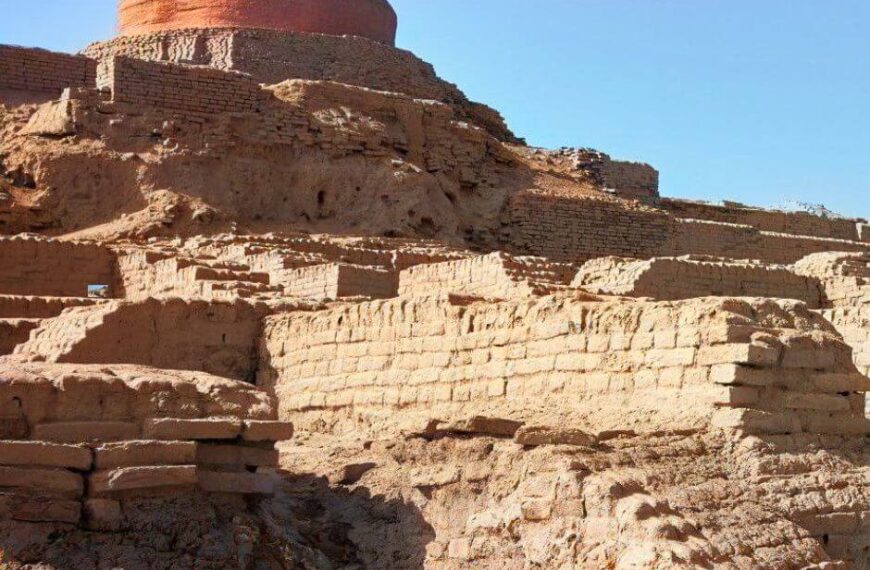

Lothal, one of the old cities of Harappa civilisation presents the world’s earliest known dockyard; the site is situated near the village of Saragwala on an ancient course of the Sabarmati River. From this site, a thick ring-like shell object was found with four slits each in two margins served as a compass to measure angles on plane surfaces or in the horizon in multiples of 40 degrees, up to 360 degrees. Such shell instruments were probably invented to measure 8–12 whole sections of the horizon and sky, explaining the slits on the lower and upper margins. Archaeologists consider this as evidence that the Lothal experts had achieved something 2,000 years before the Greeks: an 8–12 fold division of horizon and sky, as well as an instrument for measuring angles and perhaps the position of stars, and for navigation.

Lothal, one of the old cities of Harappa civilisation presents the world’s earliest known dockyard; the site is situated near the village of Saragwala on an ancient course of the Sabarmati River. From this site, a thick ring-like shell object was found with four slits each in two margins served as a compass to measure angles on plane surfaces or in the horizon in multiples of 40 degrees, up to 360 degrees. Such shell instruments were probably invented to measure 8–12 whole sections of the horizon and sky, explaining the slits on the lower and upper margins. Archaeologists consider this as evidence that the Lothal experts had achieved something 2,000 years before the Greeks: an 8–12 fold division of horizon and sky, as well as an instrument for measuring angles and perhaps the position of stars, and for navigation.

Gazing at the night sky, I wondered why the great wonders remained hidden in pages of history books only.

©Tapati Sinha

Photos from the Internet

#AncientCompass #MatsyaYantra #AncientMaritime #AncientCompassOfIndia #History #AncientCivilisationOfIndia #Lothal #HarappaCivilisation #StoriesFromHistoryBooks #NowAndThen #DifferentTruths

By

By

By

By