We are often conditioned by our biases and prejudices. This is what Soumya felt during a visit to Kashmir. A different shade of writing from our humourist, in the weekly column, exclusively in Different Truths.

A few years back, we had gone for a family vacation to Kashmir.

We had the usual apprehension that the perception of the area based on media coverage that most outsiders suffer from.

It did not help matters that the car sent to pick us up from the airport by the owner of the houseboat where we were planning to stay, was driven by a tall lean Kashmiri in black robes, skullcap, full flowing beard and a fierce scowl.

On top of it, he seemed taciturn, giving monosyllabic replies to my enthusiastic queries. We learned that he was to be our charioteer for the duration of our stay, taking us to various parts of the valley, and finally to Leh via Kargil. It was not a cheery thought.

On top of it, he seemed taciturn, giving monosyllabic replies to my enthusiastic queries. We learned that he was to be our charioteer for the duration of our stay, taking us to various parts of the valley, and finally to Leh via Kargil. It was not a cheery thought.

Assurances by the houseboat owner, whom I knew from a previous visit, that our driver was known to him, a good student, whose studies were interrupted by a tryst with militancy, didn’t reassure us much.

When the driver wanted my visiting card to help prepare his bill for the coming Leh trip, I was further worried about disclosing my identity as a government employee, and therefore a prime target for abduction.

Next day, while driving into the countryside, the heavy troop deployment along the highway made it look like we were in a war zone, a constant reminder that we are not in a peaceful tourist destination.

Having covered this route earlier on a road trip with some friends, I kept trying to show off my knowledge to my family, which seemed to thaw our escort, and he too started his guide routine.

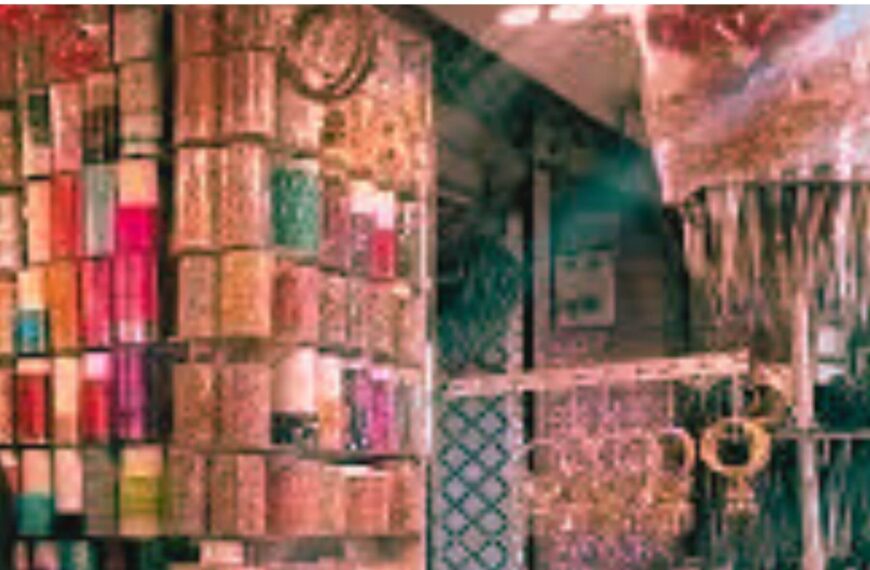

Following lunch at a place that served traditional meatballs and rice, where we were stared at as the only  tourists eating there, he took us to a tea shop which he claimed served authentic Kahwa, and his country cousin tried to sell us the raw material for the same.

tourists eating there, he took us to a tea shop which he claimed served authentic Kahwa, and his country cousin tried to sell us the raw material for the same.

After escaping their clutches, the conversation switched to food and beverages. He explained that the Wazwan we had in Srinagar was something meant only for weddings and feasts, and this meatball rice was more of a staple diet.

Similarly, the Kahwa was a rare treat, and the beverage of daily routine was Noon Chah, or salt tea, which seemed to be something like a cross between a soup and the Tibetan butter tea, having a long and complicated method of preparation.

On enquiring where we could sample it, we were told it is not sold but is always available in traditional homes. I quipped that therefore caging an invitation would be the only way we could sample it.

After thinking seriously for a while, he asked if we would like to sample it in his house. Taken aback, and too embarrassed to turn down the offer, I tried saying we would love to, but that we wouldn’t like to trouble them and needed to get back before dark. He brushed aside any objections and started speaking into his mobile phone in Kashmiri, which we couldn’t follow. Then saying that it’s all arranged, he veered off the highway into a narrow country road.

The idyllic scenery of rural Kashmir was lost on us, as the comforting sight of troops bristling with arms was no longer part of the landscape, making us really nervous. Soon, we parked outside a hamlet with crowded wooden houses and narrow dirt streets, where the car couldn’t enter and be bid to get off and continue on foot.

The idyllic scenery of rural Kashmir was lost on us, as the comforting sight of troops bristling with arms was no longer part of the landscape, making us really nervous. Soon, we parked outside a hamlet with crowded wooden houses and narrow dirt streets, where the car couldn’t enter and be bid to get off and continue on foot.

Terrified, but not knowing what to do, we meekly followed. Our mobile connections, not being BSNL, were useless outside Srinagar.

Our little procession soon drew a crowd of interested onlookers, all following us and chattering incomprehensibly. A fiercely bearded Mullah stopped us and quizzed our host for a while before letting us proceed. Visions of newspaper reports of missing tourists flashed in our minds.

Finally, we entered one of those wooden houses, went up some narrow stairs, and were bid to sit in a  largish room with wall to wall carpeting, a few scattered pillows, and no other furniture.

largish room with wall to wall carpeting, a few scattered pillows, and no other furniture.

After a tense wait, the room filled up with a bevy of beautiful Kashmiri belles, and a gaggle of giggling children, looking like a poster for tourism. Our beaming driver and I were the only males in the room.

A variety of glasses were produced, and a large flask from which the salt tea was served with a flourish, accompanied by homemade bland biscuits. We conversed through our interpreter and learned that we were the first ‘Indians’ they have met, or in fact remember entering their village, except for security men on raids.

Many photographs were posed for, and the ladies were introduced to our host’s extended family, consisting of sisters, cousins, sisters-in-law and their kids.

An hour and many cups of tea later, we returned unmolested to the car, again followed by an army of chattering children.

Darkness fell as we drove back, but it didn’t seem ominous anymore. We returned to the twinkling lights of Dal Lake, our firm opinion that all Kashmiris and all bearded Muslims are potential terrorists gone forever, as our ideas of women in Purdah being the norm in such societies completely changed. We now came to understand that Atithi Devo Bhava is a pan-Indian concept, followed even by people who thought of us as aliens from India visiting their land.

©Soumya Mukherjee

Photos from the Internet

#WhyPigsHaveWings #Kashmir #Aliens #DalLake #Kargil #Prejudice #LehTrip #DifferentTruths

By

By