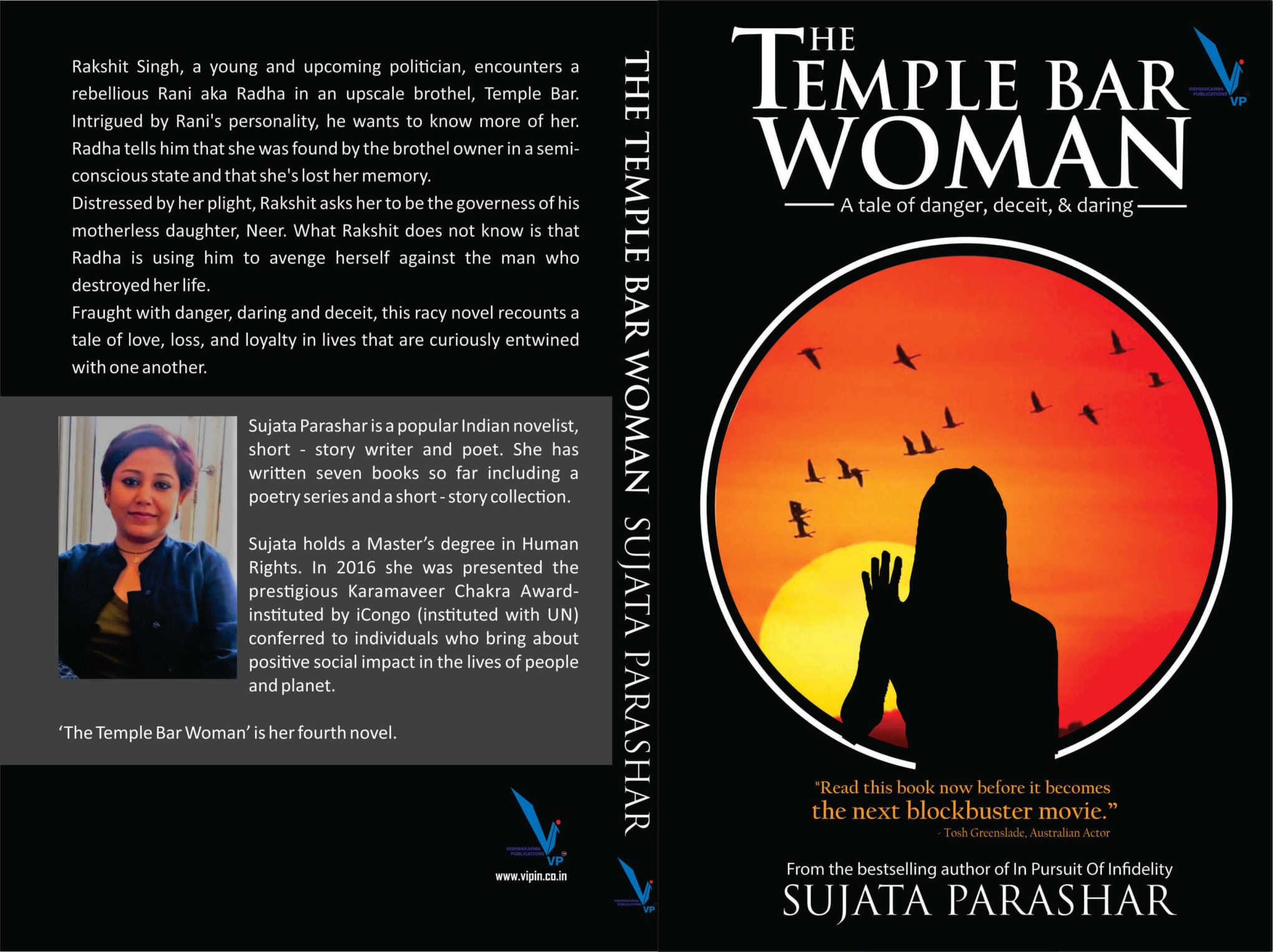

A prominent humour writer, Rachna’s fifth book, ‘Band, Baaja, Boys!’ has received rave reviews in the national media. The back cover of the book says, “She would like to work towards world peace after eliminating people who write ‘ossum’.” Here’s an excerpt from her latest book, published by Amaryllis Publishing. Beginning this Saturday, Different Truths introduces a new weekly column, Book Extract. We wish to promote authors and writing in English, as a Global Participatory Social Journalism Platform.

Brajesh Bajpai sold bras in Manphodgunj. Perhaps his destiny was sealed the day Babuji named him Bra-jesh. Under normal circumstances, Brahmins were not supposed to be businessmen. But Kumud Bajpai had brought along a hosiery shop as dowry and there was no looking back. Only front.

One glance and Brajesh could estimate, ‘Madam, 38D will be perfect.’

‘But I always take C only na, bhaisaab.’

A short trip to the cardboard-walled trial room and the customer would be wowed. And feel obliged to buy some panties as well.

‘Matching ones, madam?’ he would charm her off the matronly ones.

‘Nice, but elastic becomes loose very fast with few washes,’ she would blame the water instead of her waist.

‘No, no, this is imported,’ he would persist. And then add a personal endorsement. ‘Even my missus wears these.’

This was a lie. Kumud would never fancy panties that cost four hundred rupees apiece. She was still a middle-class girl at heart who made wipe-cloths out of Brajesh’s old vests. Born Kumud Shukla forty-eight years ago, she had grown up in the moss-walled Shukla Compound in Allahpur. She, like all her female cousins, grew up learning how to cook and embroider in preparation for marriage. In due course, she was betrothed to BA-pass Brajesh who looked like a startled Navin Nischol, with big eyes that popped out like dahi-vadas from their bed of spiced curd. Post-marriage she adjusted quickly to his eyes as well as Manphodgunj.

On some days Kumud would get Brajesh’s lunch to the store and use the opportunity to pick some stuff for herself. Pretty and petite, she had a katori face that looked like it belonged to an angel – only stung by bees. Soon enough, weight crept around her waist too and slithered down her back. Her bra straps dug into her flesh like belts around a bulging canvas suitcase, Brajesh noted disapprovingly. She worked hard to keep the focus on her face – ivory foundation, blue eye shadow, tomato-red lipstick. It worked. Till the henna-tinted hair took over in a livid orange blast.

‘Binny came here?’ would invariably be her first question.

‘Yes, she wanted some money,’ would be the usual reply.

Their twenty-year-old daughter was who they lovingly called a ‘happy-go- lucky’ girl: happy to spend her father’s money while different fellows got lucky.

When she’d turned nineteen she accepted sweet peas from the gardener’s son Roopchand, whose humongous nostrils made him look like he could smell things others couldn’t. He had worn his polyester shirt and crotch-squashing jeans for the occasion. She had rubbed his hairy knuckles while accepting the flowers. Till the buttons on his crotch almost popped out.

The encounter with Munna, her cousin from Almora, was brief. Or, to be more specific, in briefs. She had pulled his shorts down while he was busy on his phone. Playfully, like a toddler would. And then she had run around the house giggling. He had chased her and grasped her from behind. Instead of working towards escaping his grip, she had wriggled her butt closer to him, protesting, ‘Save me, save me!’

Munna-in-briefs was briefly stunned. And swollen.

Binny was now an undergraduate student and classmate Gajendra-going-bald was in love with her. He used to sit sideways on the front bench, the crook of his arm on the back of the chair, turning his head to look at her and smile and smile.

She never smiled back at him, but that did not deter him and he continued smiling. One day he went missing. Then she spotted him again, smiling at her from the window of the adjacent classroom. For he had flunked the exams and was now in a class junior to her. She had felt sorry for him, and one day at the lab, leaned over his workbench, letting her dupatta slip to allow a peek at her cleavage and pouted, ‘What is in your hands?’ A lot was in his hands later that evening.

Deep down Binny was nothing but the girl next door. She taught her maid’s children in the evenings, volunteered at Viklang Kendra, cared deeply for her parents and always stood by her friends. But the minx in Binny was brought out by those haughty Civil Lines girls.

She who had everything going for her, turned many a heads as she walked down the road to get her phone re-charged, had long luxurious frequently shampooed hair, and went only to Diana Beauty Parlour (air-conditioned), was nothing in front of those convent girls.

They were the ‘it’ girls – with short hair, readymade clothes, eyeliner on eyelids and lip gloss on lips. One could spot them cycling to school, their trendy socks folded down to their ankles and their pleated skirts rising shyly with every push of the pedal. Several diligent schoolboys would take a rather long, circuitous route from their homes to school to pay their daily respects to this rousing sight.

Those who missed the sight would go on to bunk school and head to ‘Haathi Paarak’ to sit atop the tiger there. The tiger, a rather grotesque creature made of cement and painted bright orange and black, was erected at the highest point of this undulating park. Sitting on its back, the boys could get a delicious peep into the convent school’s playfield, where the girls would be running races. On a lucky day even somersaults.

Girls like Binny, from Hindi-medium schools, never got that kind of attention. And did that make Binny mad or what? She resolved to show the boys how dumb they were. Sometimes the shows were fleeting glimpses like a jut of the hip, or a flutter of her eyelashes. Select audiences got more: it depended on how neglected she felt.

For Kumud and Brajesh, however, Binny was their innocent little China doll, made of one hundred percent pure baby laughter.

Author’s Bio:

A humorist and cancer survivor, Rachna Singh is one of India’s leading Organisational Development and Gamification experts and has consulted with leading organisations extensively within the country and outside. She has worked with Tata Motors, Infosys and Dell Computers. She writes in the areas of humour, love and organisational development. Rachna is currently writing a tongue-in- cheek diary on her battle with cancer and counselling those grappling with the big C. Her humorous debut novel, ‘Dating, Diapers and Denial’, remained on the bestseller stands for over a year. ‘Band, Baaja, Boys!’ is her fifth book.

(Contributed by Megha Parmar, Sr. Marketing Manager, Amaryllis Publishing).

Editor’s Note: Book Excerpt is reproduced as received. DT has not edited it.

Publishers, authors or literary agents may please send Book Extract (fiction and nonfiction in English language), in not more than 3000 words, including Author’s Bio. Send it to different.truths2015@gmail.com, marking Book Extract in the subject line.

©Rachna Singh, 2016

Photo sourced by the author.

By

By