Renowned author and poet, Abha, shares her experience of interacting with the students in the hinterland of India, in Kishanganj, Bihar. She attended the Seemanchal International Literary Festival (SILF), on Nov. 17-18, and participated in a couple of panel discussions to do with gender, literature and writing the short story. But what really excited her was that she would be facilitating a creative writing workshop with school children of classes 9th to 12th , from various schools of Kishanganj. The venue was Insan School, celebrating its 50th anniversary, where the first edition of the SILF was held. Here’s an exclusive report, in Different Truths.

I attended a wedding recently when the discussion of the day was pollution in Delhi, with a big ‘P’. Demonetisation had yet to make its mark on the psyche and become the prime focus of anyone’s talking circle. I mentioned, when some friends asked me what I was up to, that I would be participating in a literature festival within the next two weeks. Their eyes ignited at the idea of a literature festival, and they asked if I was going to Jaipur. No, I said, this one is the Seemanchal International Literature Festival (SILF), in Kishanganj, Bihar, on 17-18 th November. The ladies, one from Delhi and the other from the US on holiday, nodded, their eyes in withdrawal mode. Bihar was so completely out of their radar. Talk turned to pollution and the smog all over again. They didn’t even bother to ask what I would be doing there.

I would be participating in a couple of panel discussions to do with gender, literature and writing the short story. But what really excited me was that I would be facilitating a creative writing workshop with school children of classes 9th to 12th , from various of Kishanganj. The venue would be Insan School, celebrating its 50th anniversary, where the first edition of the Seemanchal International Literature Festival was going to be held. Zafar Anjum, the brain behind the publishing house Kitaab and also the founder-director of SILF, had studied at Insan School, and wanted to bring back to his roots the flavor of literature gatherings common to the metros, but unheard of in remote places like Seemanchal. [According to Wikipedia, Seemanchal region is the northeastern part of Bihar consisting of four districts – Araria, Purnea, Kishanganj and Katihar, which altogether ranks as one of the most backward region of India.]

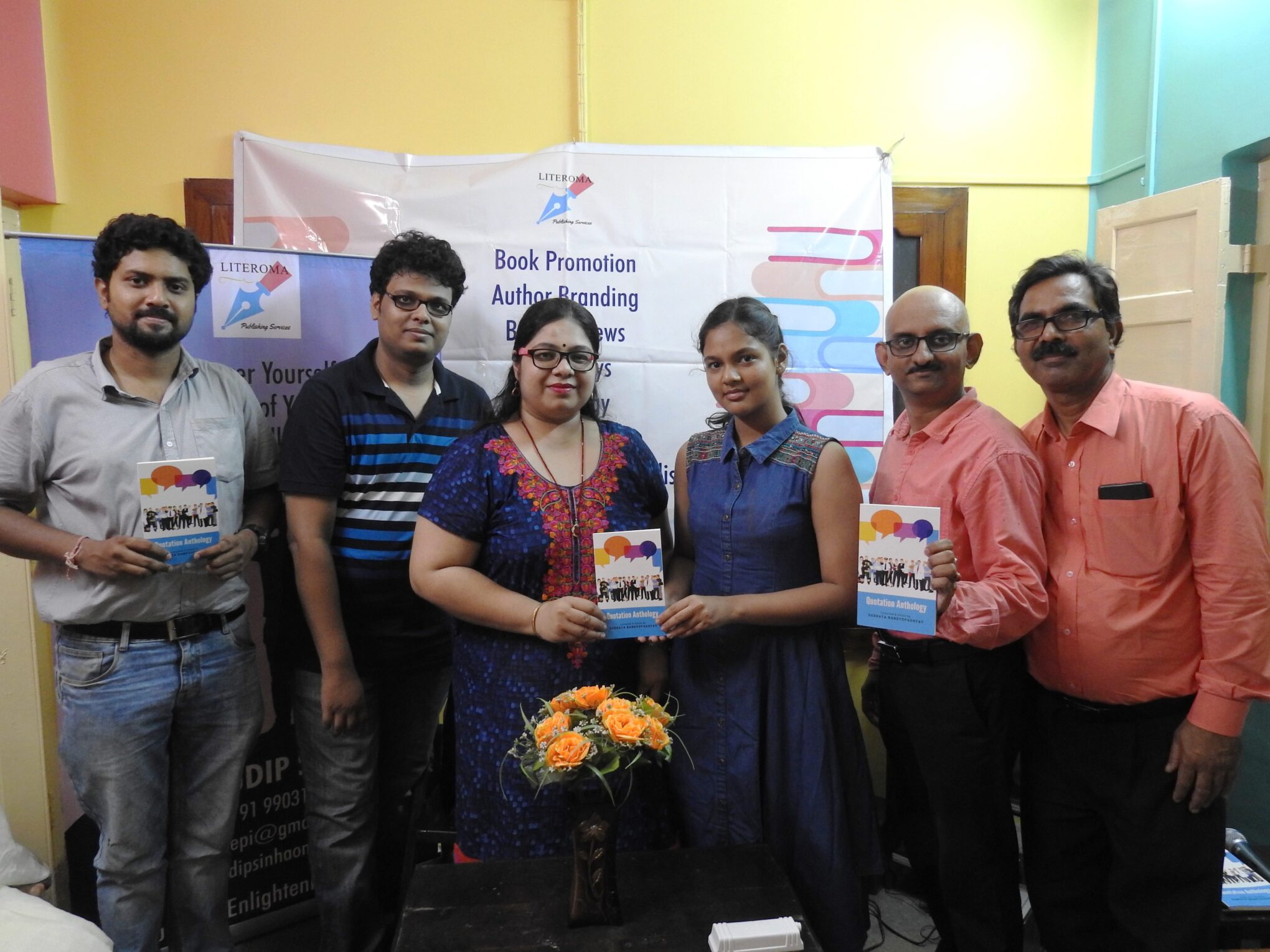

The workshop was held on the first floor of the Insan Degree College building, close to the grounds where the panel discussions were simultaneously carrying on. Rows upon rows of desks greeted me, and they began to get filled up with increasing rapidity as students poured in. Quick arrangements were made for notebooks and pens for those who came unprepared. I waited with baited breath, amazed at the response. The girls sat in the front rows, their faces eager. The boys squeezed together on the benches at the back, murmuring amongst themselves. Space was at a premium for the 80 or so students that finally crammed in, but they managed.

The white board had a fine, wavy crack running down its centre, and I had to ask for the marker and duster to be arranged, which was promptly done. There was no question of me using a pen drive or the shenanigans of technology. This was going to be an interactive session in an old-fashioned way, and I, fortunately, could handle that. More and more I have come to believe that PPT presentations take away from personal interaction, and the facilitator loses out to the screen. Students get so busy eyeing the presentation and reading the ‘writing on the wall’, that something human gets lost in the process.

There was no air-conditioning, and the afternoon heat was already making us sticky with sweat, despite it being November. I found that we could not switch the fans on since their collective whirr drowned our voices, especially mine. I was working without a mike. I took that in my stride, literally, walking up and down the hall, addressing the students, throwing my voice as far as possible. I believe I was heard, because the students listened, and listened well. They paid attention and asked questions.

I was down to working at grassroots in the true meaning of the term. And I found how enlivening it was. Learning does not require the appendages of technology. Technology is a means, but we have made it more and more a part of the centre of our dialogue and interaction. Presentations mean that you put something up there for the audience to watch. I am veering more and more towards direct human interaction in my teaching/facilitating space. It is livelier, more interactive and fun. This may be because creative writing and expression in itself does not call for hard statistics, graphs, and point-to- point explanations. But that apart, explaining anything through talk rather than presenting it on the screen for consumption…a big difference there in how it is received.

I had been requested that I should speak in a mix of English and Hindi and not fly too high with my English words. This made me a bit apprehensive, even though my Hindi is good. So, on the previous night I had roped in Rheea Mukherjee, a fellow participant at SILF [whose command on Hindi is passable but on Google Search is commendable], to look up Hindi words for basic inputs like ‘ imagination’, ‘creativity’, ‘design’, ‘literature’…you get the drift. Others in the room I shared, Jayanthi Sankar and Shubha Nair, gave their informed inputs.

So armed with an arsenal of Hindi words, I spoke to the students on the workshop day, and talked in simple, clear English, often translating into Hindi what I said. When I asked them to do an exercise using some words to form a story, I gave them the words in both English and Hindi. They could write in the language of their choice. After all, creativity requires its expression in whichever language one is comfortable in, not necessarily English. Most of them did the exercise in English, which was commendable. So if there was hesitation, they overcame it.

The girls, some with their hair covered by the hijab, stood up and spoke with confidence. They were not too shy, as I had assumed they would be; nor brash and full of themselves, as their urban counterparts very often are. I found out from the teachers that the schools are co-educational. I had thought that in Bihar, there would be complete segregation of the sexes in the educational set-up, but I was shown how wrong I had been in assuming this.

Soon enough, I managed to break what I consider to be the backbone of our schooling system, in which how one ‘should be or behave’ is delineated such that every sentence from a student tends to sound like a lesson in moral values. For example, a sentence with ‘appreciate’ would be written as:

a. We should appreciate nature.

b. I must learn to appreciate the hard work of teachers.

A paragraph by them would also be along the same lines. Sigh!

We overcame this hurdle when I asked them to stop thinking or talking of ‘shoulds’ and ‘musts’, and soon we were exploring situations and themes. We actually worked with the story of 6’0 tall, ‘stylish’ farmer aged 25, who did not want to be a farmer and stole his father’s money to take a train to Mumbai. ‘Stylish’ was defined as one wearing tight pants and T-shirt and riding a motorbike! There were various renditions to the development of this tale, fraught with love, betrayal, and thwarted ambitions. Two of the girls came up with the best story versions.

The one-hour workshop extended to three hours, and eventually we gave in to the call for lunch. Hunger for the written word had been satiated for a while. I came away hot and tired, with a singing heart. The state of Bihar has youth willing to tell their stories and speak their minds. They are bright and pro-active, and that is very good news, and an eye-opener for us in places like Delhi, who think of Bihar as the back of beyond and backward. Well, I can now tell you different.

©Abha Iyengar

Photos by the author.

By

By